Issue 2/2013 - Net section

Spray can politics

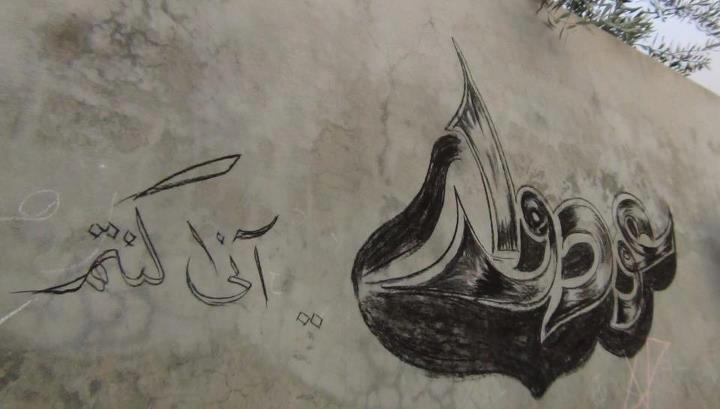

Egyptians and Syrians discover graffiti as a means of public commentary

The left side of the face belongs to the ousted dictator Hosni Mubarak. The right side stems from his successor, the longtime military leader Mohamed Hussein Tantawi. People who want to take another amused look at this graffiti in Cairo's Muhamed Mahmoud Street a little later on are surprised – and amused once more. Mubarak's square chin and Tantawi's malicious eyebrows have been supplemented by the dewlaps of Amr Moussa (chairman of the new Conference Party). Finally, the furrowed brow of Ahmed Safik (ex-premier under Mubarak and presidential candidate) is added. And a few weeks later, a chubby cheek belonging to the incumbent president, Mohammed Morsi, bulges out imposingly towards the viewer.

It is indeed a veritable feast for the eye and the brain cells that the graffiti activists put on display in Muhamed Mahmoud Street – starting way back in November 2011. That's when Egypt's so-called second revolution broke out and the fury of Egyptian citizens at their overabundance of authoritarian leaders again erupted on Tahrir Square, which is surrounded by almost all the important institutions in the country. The physical struggle on this square is considered as embodying the message itself, so it is no coincidence that the battle with the spray can is continued in Mohamed Mahmoud Street: it is situated directly behind the square. Its walls have since been viewed as the barometer of the revolution. The political commentaries compete with one another – not least to gain the favour of the passers-by, whom they constantly give new food for thought. Very much to the chagrin of the authorities, who would invest anything to restore an orderly silence, and in fact do so – spending huge quantities of Egyptian pounds on white paint and master painters. But it almost seems as if the graffiti artists are delighted at the blank slate that this regularly provides them with – after all, it saves them the trouble of painting over the works of other activists and causing rivalries. Because, of course, the street is a showcase not only for the protest culture, but also for artistic vanity. Alaa Award, in particular, aroused hot debate. This young lecturer of Fine Arts at Luxor University spent almost the entire winter of 2011/2012 on th street, and created large-scale scenes in the style of Ancient Egyptian wall paintings, such as one based on a picture in the funerary temple of the pharoah Rameses II. A crowd of women climbs up a ladder that, according to Awad, symbolises the revolution. With this tribute to the courage of Egyptian women in the struggle against Mubarak and the reference to thousands-of-years-old expressions of respect towards women, Awad doubly repudiates the modern Salafist darkroom culture.

But neither the Salafists nor the master painters were responsible for the picture's disappearing again. That was the work of Awad's fellow graffiti artists, who summarily painted over it in protest at Awad's wish to seal his work permanently with varnish. After all, they maintain, graffiti is per se an ephemeral medium, and the revolution is by no means over. The public space must remain accessible to everyone, they say.

To whom do Syria's walls belong?

For the time being, Syria's spray can activists can only dream of having the leisure to create epic wall paintings or for debates on the definition of graffiti. In Syria's rebellion, the most murderous of all Arab uprisings, graffiti is created in highly dangerous blitz operations. Mohammad Ratib, the “Tiger” of Homs, or the 23-year-old Nour Hatem Zahra from Damascus have already paid for them with their lives. The latter became known as “Al-Rajou al-Bakhak” (the sprayman) – named after the title of several episodes from the popular Syrian sketch series Baq'et Dau (Highlight) of 2008. In the series, a sprayer, appearing and disappearing in phantom-like manner, enfuriates the authorities. He is finally silenced, but his example attracts copycats. The episodes got past the censor at the time, something the authorities obviously cannot forgive themselves for: the author of the script for Al-Rajoul al-Bakhakh, Adnan Zirai, was arrested, as if in retrospect, in February 2012.

The state security organisation, however, already indicated the huge threat it sees in every graffiti at the start of the revolt: when some children, overwhelmed by the events in Tunisia and Egypt, scribbled “The people wants the regime to be toppled” on the walls of Daraa in March 2011, it was enough reason for the authorities to imprison them and pull out their fingernails.

Despite – or precisely because of – the explosive force of this activity, a considerable graffiti movement has developed in Syria, differing from the Egyptian one in that it operates all over the country, as it lacks a central location that it has conquered for itself. The biggest difference, though, is that the Syrians are not experiencing the painful aftermath of their rebellion, but are right in the midst of it. For this reason, each party tries to mark public territory as their own. While the activists laugh with bared teeth and primarily make fun of the president – for example with “Down with the giraffe” in allusion to Bashar al-Assad's neck – the armed rebels put on a rather pathetic, and sometimes offended, demeanour. “Sorry for the trouble, but we are dying for you” can, for example, be read on the walls of Aleppo – a reaction to furious residents who blame the rebels for the major operation by the army. The regime's henchmen, on the other hand, put up the sentence “Assad forever. Or we'll burn the country down” all over Syria.

More efficient than Facebook

In the struggle for public opinion, the media are also literally put against the wall. For example, at one corner the slogan is displayed: “Syrian television lies” – and at the next, just one word: “Al-Jazeera”. To illustrate what they think of the station's reports, which tend to be critical of the regime, the loyalists have written this on almost every rubbish bin.

At the outset of the revolt, when many things were still unclear, such slogans gave many a passer-by pause for thought. Precisely for this reason, Marwan Kraidy, professor of Communcation at the University of Pennsylvania, believes that graffiti have much more potential to mobilise people than social media such as Twitter and Facebook. This theory makes sense if one considers that, according to ITU World Telecommunication, only 20 out of 100 Syrians and 26 out of 100 Egyptians were using the internet in 2010 – while the messages on the walls reach everyone.

Translated by Timothy Jones