Issue 4/2013 - Net section

Napsterizing the Teamsters

On emerging forms of mutual aid and collective bargaining

Today, when business leaders discuss what they call the „sharing economy,“ they are actually referring to digital labor that is frequently coerced and exploited. Such digital labor is about the production of data for surveillance projects with codenames like PRISM and BOUNDLESS INFORMER, run by the National Security Agency, and it is also for the economic profit of actors like Facebook/Google/Twitter.

Then there is also the ever-growing crowdsourcing industry, which is comprised of at least 10 million workers in 2012. Add to that 42 million American freelancers and the 20,000 workers in Japan who die every year because of Karoshi and Karo-ji-satsu. Karojisatsu is suicide caused by excessive stress and K`aroshi refers to death-by-overwork.

Today, we are all unemployed on probation; and the worry about career and jobs unites generations.

First, we need to detail these emergent work practices if we want to stand a chance of changing them. Digital labor is part of the daily reality of millions of people all over the world but I will only discuss one small aspect: AMT.

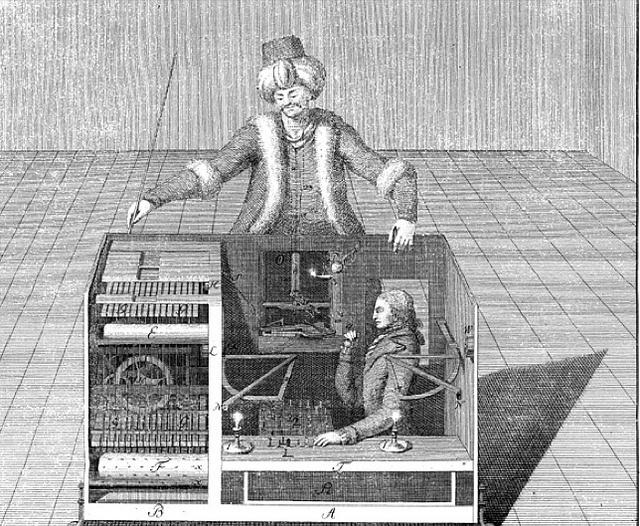

Founded eight years ago, Amazon Mechanical Turk is an online crowd sourcing system designed for corporate labor-management. The name pays homage to the 18th century machine that tucked away a human within its system. A small-bodied chess player was hidden in a compact wooden box to control the mechanical hands of a Turk. The automaton was a hit in Europe with Charles Babbage and Edgar Allen Poe counted among its admirers.

Today, Amazon Mechanical Turk has 500,000 registered workers with 50% of them living in the United States and some 32% in India. People apply the mantra of flexibility that is always handy when it comes to any kind of freelance work. AMT workers often do not know what they are working on, they don’t have any information about the identity of the employer, and obviously, they don’t have contact with the other workers.

18% of the workers on Mechanical Turk are attempting to make a full-time living on the site, which is practically impossible as even experienced workers generally make no more than $2 per hour, which is also the going hourly rate for companies like CrowdSPRING, and many others.

While Amazon choreographs this rote, repetitive, and potentially exploitative work, it insists that it is a neutral bystander who does not get involved with any labor disputes on the site.1

How does AMT work? Well, Mechanical Turk allows you to break down tasks into thousands of pieces. Work assignments typically include the tagging and labeling of images, the transcription of audio or video recordings, or the description and categorization of products. Some researchers use it for social science surveys.

Imagine that you need to make a small change to 4000 images, for example and let’s say Photoshop can’t automate that specific task. If you hire a single worker to do the job, it’d be far more costly than asking 1000 Turk-workers to alter 4 images each, paying them 2 cents per task.

Work is reorganized against the worker.

Felix Stalder, in a recent keynote on digital solidarity, linked forms of digital solidarity to practices of sharing, which he described as productive and sustainable in cases like Wikipedia. Sharing, then, is understood as contribution to the existence of various institutional forms associated with the commons. Other issues that are part of this discussion about network cultures on forums like Netzpolitik.org are transparency, open standards, digital rights, free software, „the backstage politics of Google,“ Google’s „down ranking“ practices and the struggle against post-privacy ideologues who claim that data protection is no longer necessary. I would like to expand this notion of digital solidarity beyond sharing and add an emphasis on digital labor, which is hard to find in this context.

In no small part because of the global recession that set in 7 years ago, the fields of digital labor are blossoming. Crowdsourcing platforms continue the attempts by Taylor and Ford to make production processes most effective, but now, there’s no consideration for the worker to be able to afford what she produces. The firms operating these platforms continue the work that Thatcher and Reagan started when they broke the spirit of unionized flight traffic controllers and miners.

Employers get all the work without the worker, as Alex Rivera put it in his film Sleep Dealer. No commitment, no care for the worker, just a superabundance of a global 24/7 workforce.

Digital labor and crowdsourcing in particular set back the clock for organized labor to the second half of the 19th century when the 80-hour week was the norm.

Digital labor defeated hard-won achievements like minimum wage, employer-paid health insurance, paid vacation, and the abolition of child labor. On the other hand, digital labor performed within the context of peer production largely escapes those dynamics.

Unions, organized networks, or associations are important because they could lobby for the application and enforcement of Federal Labor law online, which could change the entire industries that profit from online work. Changes to US labor law could have global repercussions as Google/Amazon/etc are responsible for the bulk of digital labor. Unions could inform workers of their rights, fight for more ecologically sustainable work environments, challenging their status as „independent contractors“ with coordinated campaigns, and document, as well as publicize unfairness.

To become relevant to this very large and growing workforce, unions would have to completely restructure and for that, they have to understand some of the obstacles that they’re facing. I am naming just a few of them.

Anonymity of the workers and employers is one of the biggest problems for unions because without access to the workers they can’t run organizing drives. These are not the days of On The Waterfront; today Marlon Brando, aka Terry Malloy, would be on Facebook. Sure, Foxconn workers could use Facebook, Qzone, and RenRen to inform other workers in Shenzhen about union campaigns but it wouldn’t be safe to organize on those platforms.

Traditionally, there were capitalist owners on the one side and the mass of workers on the other, frequently represented by a union. Today, there are anonymous individuals, facing anonymous employers, in some cases. Unions cannot easily represent workers through firm-by-firm collective bargaining because workers have contracts with more than one company at a time.

Another question is that of scale. ODesk and Elance, for example, each manage somewhere between 2.5 and 3 million deeply individualized workers. We might add at this point that another serious threat to unionization is automation, the replacement of workers with machines. Think of Amazon.com, which with its acquisition of the robotics company KIVA already paved the way for the replacement of the workers in its fulfillment centers.

Yet another problem is that of identity. Just like bike couriers or workers in a fast food joint, some digital workers might only sign on for five hours per week and don’t even think of themselves as workers. NYU professor Ross Perlin reminds us that the full-time intern, for example, might still self-identify as a student. She might not think of herself as a worker; for her this is just a transitional occupation. The current efforts to unionize fast food workers all across the United States, faces similar problems.

On Amazon Mechanical Turk, many people get busy after their regular job is done; they do it instead of watching television or playing video games. They don’t think of what they are doing as labor. The division between work/play, work/consumption, and work/entertainment and work/leisure is blurred beyond recognition.

Working on AMT is also a way to feel part of some kind of John-Wayne-frontier-saga of techno-utopianism; it is considered cool. Tom Sawyer’s whitewashing the fence for the 21st century. Why call for union representation; this is way coooool.

Lastly, it appears to be hard for workers to reach legal recognition as a „community of interest“ in the case of such a trans-nationally distributed workforce, which could then function as a bargaining unit. The last time a case like that was heard in a US American court was 1995. Professor Ursula Huws reports that in the Caribbean and in Brazil there have been successful organizing drives of „e-workers“ but such efforts were always limited to national boundaries (Huws and Leys 19). Two national unions for Mechanical Turk workers, in India and the United States, would be a first and perhaps possible step.

There are precedents of unions that overcame equally difficult situations.

In the early 1960s, Cesar Chavez cofounded what was later called the United Farm Workers Union (UFW), which unionized migrant farm workers while moving with them from field to field. Under Chavez’s leadership, the UFW organized consumer boycotts against nonunion grapes and lettuce, which eventually, after several years, lead to higher wages for these migrant farm workers. Historically, this is important because organizing migrant farmworkers was considered impossible.

Equally, unionizing Walmart workers has been deemed impossible and yet we witnessed a serious intensification of efforts for unionization in that sector in the last year. In his book For the Win, Cory Doctorow plays through a successful scenario of unionization of gold farmers2.

Or, remember the great victory of 2012 when the Stop Online Piracy Act– SOPA for short – was defeated, at least for now – after GOOGLE AND WIKIPEDIA and countless others switched their websites to black on January 18, 2012 and senators received millions of e-mails, countless phone calls and letters, etc. Elected officials suddenly realized that SOPA could become a voting issue.

So far, the crowdsourcing industry hasn’t seen much opposition from workers but there is one such site of resistance in the making: Turkopticon.

TURKOPTICON, is a web-based design intervention that is already used by more than 7000 Mechanical Turk workers. Technically, Turkopticon is simply a browser extension for Firefox and Chrome. Lily Irany and Six Silverman built a system that allows workers to connect and evaluate their employers in terms of their responsiveness when it comes to communication about worker concerns, their fairness when it comes to their pay rates, and also with regard to the legitimacy of them rejecting work. The designers of Turkopticon insist that employers should have to provide a reason for rejecting work that has been already performed.

On its landing page Silverman and Irany state that Turkopticon helps the people in the „crowd” to watch out for each other –because nobody else seems to be.“

While online hubs like Turker Nation and MTurkforum already exist, Turkopticon really changes the situation of the worker who is no longer faced with an anonymous employer but who can now connect with others like him or her to coordinate, recommend, complain, and possibly decide to boycott a particular employer. The goal of the tool is to induce better corporate behavior and inspire press attention.

Turkopticon can teach us how to expand the capacity for action to eventually overcome the current stalemate of digital labor. The tool also finds historical resonance with the history of German wandering apprentices (Wanderleute) who shared information about the businesses that took them into their employ.

Today, you face a decision: you can either wait for the immaterial worker movement to materialize or you can help to shape coalitions that will help to meet collective needs. One thing is clear: without outrage, conflict and protests digital solidarity and mutual aid will not be able to make significant strides.

References

Huws, Ursula, and Colin Leys. The Making of a Cybertariat: Virtual Work in a Real World. Monthly Review Press, 2003. Print.

Jackson, Joab. „Google: 129 Million Different Books Have Been Published. “ PCWorld Aug. 2010. Web. 5 Oct. 2012.

1 Already in 1994, when Bezos founded Amazon, he described it as a „regret minimization framework, meant to fend off late-in-life regret for not staking claim in the Internet gold rush.“ (Jackson)

2 Gold farmers, mostly in China and India, are players in massive multiplayer online games who acquire in-game currency or elevate the status of an avatar to then sell it.