Issue 3/2014 - Arab Summer

Geographies of Fear

The impact of the Syrian conflict on the Lebanese cultural scene

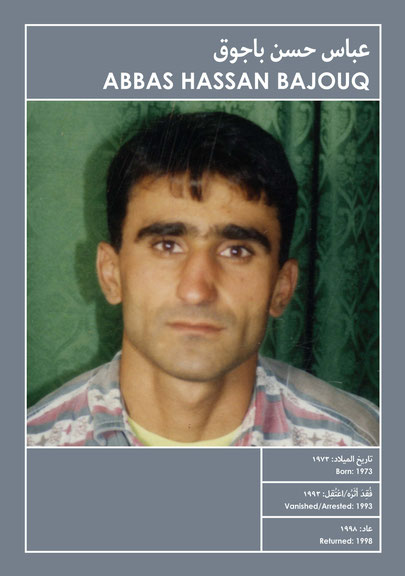

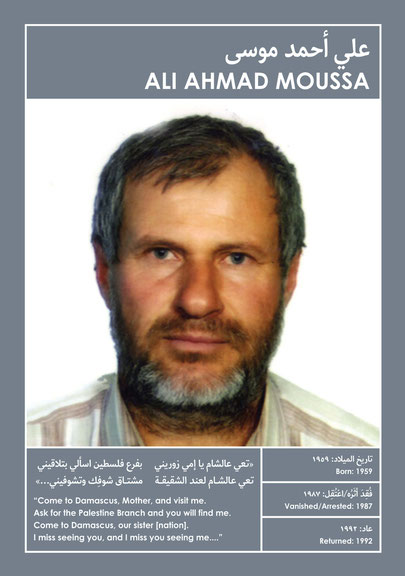

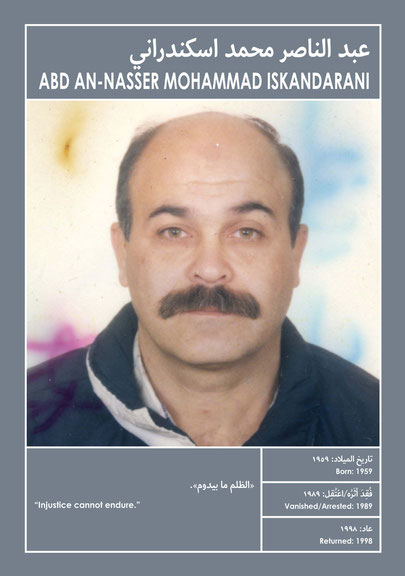

Monika Borgmann is not very popular in her neighborhood. This has less to do with her being a “tall blonde” from Germany and thus a native of the suspiciously eyed West than with her husband, Lokman Slim. Slim is a Lebanese Shiite who lives and works in his family’s ancestral mansion. This would be nothing remarkable if the house weren’t located in Dahieh, a suburb south of Beirut that is almost completely under the control of Hezbollah. Slim however rejects the “party of God” outright. And proclaims so publicly. He also knows just how to annoy his neighbors with his own organization, Umam, which does art and theatre projects that regularly attract outside visitors to Dahieh. This is quite a nuisance for the self-anointed masters of the precinct, who are at pains to screen it off from the outside world, while at the same time a source of amusement—and belligerent pride—for Slim and Borgmann. At least it has always been that way since Umam’s founding in 2004. Recently, however, Slim and Borgmann made the decision not to present the exhibition Damascus Road in their home as planned, and relocated the show to a “neutral hotel in central Beirut,” as Borgmann puts it. This is because Damascus Road shows pictures of former Lebanese prisoners in Syrian jails and is geared not least toward those very prisoners, as a way to help them process their experiences. And these viewers certainly do not want to relive their suffering in the stronghold of those now allied with the Syrian regime. This is more than understandable, and yet, after Umam announced that it would in future be organizing as many projects as possible outside Dahieh, one can’t help wondering what has changed.

Beirut intimidated, Tripoli paralyzed

The answer is: Syria. Traditionally, Lebanon has been regarded as a country that suffers a bout of the flu every time its “big brother” does so much as sneeze. Based on this Arab joke, we should congratulate the Levantine nation for continuing to exist at all given the hell that erupted three years ago just across its border. Despite its relative stability, however, Lebanon is still far from immune to the political and religious causes of the war in Syria. As if in faithful allegiance, it has long since harbored exactly the same enemy camps. This can also be felt on the cultural scene. What was once a mixed, ideologically open-minded audience is becoming increasingly rare at openings and premieres. And such viewers are practically absent altogether in places regarded as centers of the “other” (however it may be construed). The Lebanese are instead returning to the behavior they practiced during their own civil war (1975–1990): Each denomination is withdrawing, both mentally and physically, to its own city district. The Lebanese Film Festival scheduled for January 2014 in Beirut therefore had to be postponed indefinitely—because the organizers feared the lack of an audience.

Nevertheless, anxiety and suspicion among adversarial ethnic groups in Beirut is still merely simmering below the surface. In Tripoli in northern Lebanon by contrast, it hangs like a smothering smog just above the city. This is hardly surprising, because for decades now, what might be a thriving port city has been held hostage by the authorities to a regime of material impoverishment and religious stultification. Tripoli today stands only for unending sadness and for seething hatred, mainly between Sunnis and Alawites. The fact that precisely these two groups are now fighting an internecine battle in Syria further fuels the propensity for violence in the neighboring state. In early January, the murderous mood even affected a denomination that is usually beyond the fray, with the Greek Orthodox priest Ibrahim Surouj as target. Unknown perpetrators set fire to his life’s work, the Al-Saeh Library. The 70-year-old Surouj had amassed over 85,000 books and manuscripts in the course of over four decades. Now Lebanese security forces report that two thirds have been damaged beyond repair—and Surouj himself speaks of a loss of 20 percent of his holdings. Regardless of the extent of the damage, it is certainly dire enough, for among the scorched works are allegedly Christian writings as well as over 200-year-old Islamic treatises, along with documents on the history of Tripoli and Judaism. One work that was however never housed at Al-Saeh, Surouj points out, was the pamphlet mocking the Prophet Mohammad that probably motivated Sunni extremists to commit the book burning in the first place.

Cultural resistance?

Last fall, the filmmaker Jocelyne Saab decided she had had enough of the agonies suffered by Tripoli, even in between bouts of violence. To bring a breath of fresh intellectual air to the city—and some positive media coverage for a change—the 66-year-old organized an international film festival on short notice. The motto was to be cultural resistance. This is just what is urgently needed, says Saab, to roll back the “my clan and no-one else” mentality that is increasingly ruining the country. She showed films dealing for example with women’s rights and doing so from a “completely different” perspective—among them the feature-length Syngué sabour (The Patience Stone) by Franco-Afghan director Atiq Rahimi and the documentary Salma by Kim Longinotto from India. To spread inspiration throughout the city, Saab had the films screened at different locations in Tripoli—encouraging residents to reclaim the entire urban space as their own.

As encouraging as Saab’s initiative is, it will hardly be able to have an impact as long as politics—especially that of the religious scholars—remains rigid. At the moment, the various stakeholders are defending their respective benefices more fiercely than ever, especially since the influx of hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees into the city of four million have been driving it to the limits of its capabilities. Among the migrants are numerous artists who have come to Lebanon in order to survive. After finding here similar conditions to those they have fled, however, many of them view any step in the direction of change as a pointless exercise that could possibly be life-threatening. The fatalistic wheel thus continues to turn. Constructive interactions are now less likely than ever.

Translated by Jennifer Taylor