Issue 3/2014 - Arab Summer

A Labor Camp Is Now Known as a Village

Interim report on the artist and human rights initiative Gulf Labor

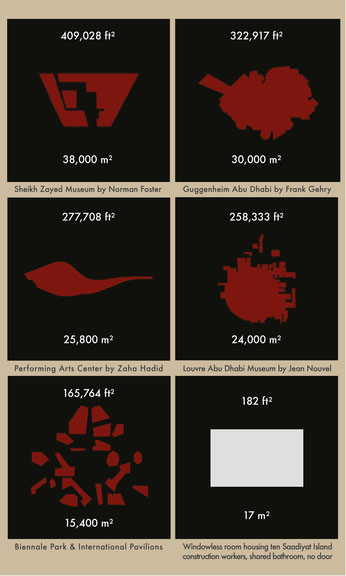

“Saadiyat Island ... 500 meters off the coast of Abu Dhabi … [will] within a decade, if the $22 to 27 billion development plan goes according to the schedule … host six cultural institutions, including outposts of the Guggenheim and Louvre museums; a museum dedicated to … the UAE’s first president, Sheikh Zayed; a Maritime Museum; a performing arts center; and a campus of New York University. It will also include two golf courses, expensive private residences, a marina, and 29 hotels.”1

Thus began the 2009 report by Human Rights Watch, which for the first time investigated working conditions at the Saadiyat Island construction site. Since then, the island project has often been cited as an example of the problems involved in global franchising by major museums in countries with strong economies but repressive systems. When we visited Abu Dhabi in 2008, we were amazed at the extent of the master plans being hatched by the consulting group Booz Allen Hamilton, and by the portrait of the Prince with a hawk perched on his fist that dominated the exhibit on the project. In this “world-class culture district,” it became evident “that the authoritarian system is the ideal political partner in a so-called free market.” 2 In the meantime, this apparent insight has become commonplace in our everyday experience. We know only too well how the spectacles presented by authoritarian regimes can involve equally spectacular conditions of exploitation: Sochi, the FIFA World Cup in Brazil, and “Marie Antoinette Beckenbauer,” who for the life of him cannot detect any indentured servants on the stadium construction sites in Qatar. But we do see every day the Polish, Romanian, Ukrainian, Greek, and Spanish workers who live in the ground-floor apartments all around us, six to a room, the flats subleased for example to make way for the luxury real estate boom in Berlin. What are we to make of these encounters, and how do we escape the numbing sedation brought on by the toxic combination of empathy and powerlessness? With regard to the working conditions on Saadiyat Island, the Gulf Labor initiative has managed to overcome this inertia, by applying the classic instruments of boycott and negotiation.

The Saadiyat Island Report published by Human Rights Watch was a specific case study of the general working conditions that were set down in 2006 for the entire United Arab Emirates (UAE).3 The main criticisms of these regulations have not changed since then. They are: 1. Debt bondage: The workers are recruited by agencies in their homelands (currently in particular Nepal, Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh) for a recruitment fee of up to $4,100, putting them in debt for several years; often, the family takes out a credit on its land or it sells the land to pay the fee. 2. The “sponsorship system” traditional in the UAE, under which the employer retains the workers’ passports and thus determines the length of their stay. 3. Segregation: The workers are housed in labor camps far away from the city, forced to rely on the employer for transport and to live in conditions that are often unfit for human habitation. 4. Ban on trade unions: The many worker uprisings are put down with arrests, torture, and deportation. 5. The subjection of the workers to the arbitrary whims of their bosses: “There is no arrangement for cold water … The boss will ask us, ‘Why are you going to the water so many times?’, so we can’t go too often. Sometimes I have a headache, fever. It’s not that serious—I never went to the clinic.”4 (Nurredin A., from the Punjab Province, Pakistan)

In 2009, Human Rights Watch began to confront the Western business partners in the project—the Guggenheim, Louvre, British Museum (as consultant on the Sheikh Zayed Palace Museum)—and the architects Gehry Partners, Ateliers Jean Nouvel, Foster + Partners, Tadao Ando Architects, Zaha Hadid Architects, and Rafael Viñoly Architects with this report, urging them to institute fair working conditions as part of their cooperation agreements. While the architects, displaying the professional callousness of their industry, tried to shift the blame onto their subcontractors, the Guggenheim Foundation in particular felt obliged to respond to the report. This was mainly due to pressure from Gulf Labor, a network of international artists and students at New York University that works closely with Human Rights Watch. In June 2010, Gulf Labor wrote a letter to the Guggenheim Foundation that was signed by 43 artists with ties to the collection. The artists threatened to call for a boycott if the Foundation neglected to demand a guarantee of workers’ rights by its contract partner TDIC (Abu Dhabi Tourism and Development Investment Company). The letter was followed by meetings with Richard Armstrong, director of the Guggenheim Museum, and chief curator Nancy Spector.

“They … requested some time to pursue the development of employment policies with their partners in Abu Dhabi, TDIC … We agreed not to make our letter public in the meantime … September 2010: The released statements made public commitments by TDIC and the Guggenheim Foundation to uphold workers’ rights protections. However, the released documents did not address independent monitoring of employers’ compliance with human rights standards, and about effective enforcement mechanism … In subsequent communication with the Guggenheim Foundation, we urged them to address this and other considerations such as provisions related to the payment of recruitment fees, freedom of movement for workers, health and safety provisions, accommodations, monitoring of wage payments, and rest and leisure time for workers, among others … March 2011: Gulf Labor coalition noted little progress on issues … We decided to make our letter public and announced a boycott of Guggenheim Abu Dhabi.” 5

The initiative thus responded resolutely to the vague declarations of intent on the part of the companies and institutions. Reading the further progress of Gulf Labor’s timeline, we can’t help being impressed by the toughness they displayed in negotiating with the Guggenheim Foundation and with the TDIC in Abu Dhabi. In addition to other meetings with the Foundation and visits to Saadiyat Island, Gulf Labor also organized various actions, including the internet campaign 52 Weeks, in which we also took part. 6 Nearly 2,000 artists have signed the boycott so far. This is a large number for the organization-phobic and financially fragile arts and culture scene. Many of the signatories are well-known artists, and an especially large number come from Arab countries. This may explain why the Guggenheim Foundation feels the pressure more keenly than the Louvre.

The negotiations between Gulf Labor, the Guggenheim, and TDIC mainly concerned the need for impartial monitoring of working conditions. In 2011, TDIC enlisted the company PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) to do such monitoring. PwC is one of the world’s largest auditing firms and, in addition to its central position in the neoliberal restructuring of corporations and institutions, has a longstanding and unequivocal reputation in the labor rights field, as demonstrated by an initiative to occupy PricewaterhouseCoopers in Bern in 2002: “PwC is the largest provider of such company inspections for corporations that want to be externally audited concerning environmental issues and working conditions. NGOs have long criticized the lack of objectivity of such inspections since the audited company is both the client and the one paying the bill ... The inspectors from PwC primarily asked managers about working conditions instead of speaking directly with the affected workers; they overlooked the lack of safety precautions, faked time cards, and the use of toxic chemicals.” 7

Continuing to peruse Gulf Labor’s timeline, we get the feeling that the reports and the responses to them have taken on a life of their own. In March 2012, Human Rights Watch published an update of its 2009 report. After much urging, PwC then published its monitoring report in September 2012. One month later, Gulf Labor in turn responded to this report. And finally, Gulf Labor’s own report followed in March of this year, which was answered by a letter from TDIC on May 7th. The central points covered in all the reports can be summarized as follows: “notable improvements in some areas, particularly in the regular payment of wages, rest breaks and days off, and employer-paid medical insurance. However, workers continue to report indebtedness for recruitment fees … misleading information, about their terms of employment before arrival in the UAE … illegal salary deductions; and, for some workers who did not live in the Saadiyat Island Workers’ Village, overcrowded and unhygienic housing conditions … Only one worker of the 47 we interviewed reported that he retained custody of his passport.” 8

The report by Gulf Labor is structured similarly to the others. It makes similar “main observations, recommendations, and detailed findings,” as well as mentioning that PwC interviewed only residents of the new workers’ camp. The report uncovered worse living and working conditions in the workers’ camps for the NYU construction site and recommended and insisted on improvements, evincing concern.

Why do we become so bleary-eyed when reading these ongoing reports, and how much more respect do we then owe to those writing them? This is all about the struggle to wrest facts/ cases/ res gestae from continual routine human rights violations so that those responsible can no longer claim they were not informed, and so that the blame cannot be laid at the feet of the subcontractors. The workers are not representing themselves in this battle. In 2011, a brutal, world-leading facility management firm was put in charge of dealing with the uprisings, namely the mercenaries from Blackwater, 9 as if the revolts were not a constitutive political act but something to be disposed of. The rights of the affected workers are thus now represented by “intangible producers”—producers of that imaginary freedom of expression and democracy that the museum delivers to the authoritarian regime in the form of diplomatic expertise in a universal standard of compliance with “minimum human rights.” But even this expertise is negotiable: “Rita Aoun Abdo, Saadiyat’s cultural director, said the museums had to grow within the local culture … ‘They’re based on real dialogue not on shock or controversy. How would you define censorship? Is it based on local or international values? Censorship has always existed and it’s just the respect of what are the values of the place.’” 10

The practice of militant research was established in the late 1950s in Italy. This was the beginning of Operaismo, or workerism, a vigorous revival of the Marxist postulate of the working class as the engine of history, which is antagonistic to capital—rather than “recommending, concerned, and insistent.” A generation of intellectuals without a clear mandate carried this postulate as an autonomous demand and political wishing machine into the factory and later far beyond it. It invoked the “Worker’s Inquiry” that Marx had written some 100 years earlier, wherein the inquiry and a rising awareness form a unit that is still painfully relevant today all over the world. “The experience of research militancy resembles that of the person in love, on condition that we understand by love that which a long philosophical tradition—the materialist one—understands by it: that is … a process which, in its constitution, takes two or more … This is … an authentic experience of anti-utilitarianism … In love, in friendship … there is neither objectuality nor instrumentalism. Nobody restrains him or herself from what the tie can do …we all come out from them reconstituted.” 11 This is how the group Colectivo Situationes described talks held with groups of unemployed persons in 2002, at the height of the new social movements in Argentina. This model for applying the Socratic method for revolutionary purposes can work only in a few lucky cases of rebellion and is certainly not conceivable in the UAE. But shouldn’t we insist on it? Or do we choose to be blind to the fact that, with the end of Fordism, its class-specific antagonisms are also disappearing?

Workerism not only provides an answer to the late-era Fordism of streamlining and the mass deployment of workers but also vehemently reacts to the left-wing parties and trade unions that refused to abolish this regime but instead played by its rules through collective bargaining rituals and socially acceptable complicity. David Harvey has pointed out repeatedly that the political constitution of the NGOs that sprouted alongside neoliberalism mirrors the neoliberal structure: “attempting to roll back a market ethic by a logic of individual rights, when the market ethic is based on the logic of individual rights.” 12 Both sides invoke the universality of individual rights. While one side needs this universality as a global ethic for enforcing its interests in the accumulation of wealth, the very same universality on the other hand particularizes in the many individual cases “accumulation by dispossession,” as Harvey refers to the current paradigm of capitalist exploitation. It would be precocious and banal to point out that the utter asymmetry of money and power under which the grueling legal or petition-based procedures unfold in the individual cases let every partial success degenerate into a philanthropic farce. “The official name of the labor accommodation site (SAV) on Saadiyat Island is ‘village,’ not the more commonly used ‘camp.’ Village life is often what is left behind in the great migrations for work all over the world, and this name seems to invoke a re-creation of community … where outside supervisors are still addressed as ‘camp bosses.’” 13 Thus begins—sensitively and clear-sightedly enough—the report by Gulf Labor on the newly built accommodations for a small portion of the many workers in the UAE. On the photo it looks like Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon, that well-known architectural hybrid made up of philanthropy, surveillance, and labor camp.

It may sound arrogant and cynical given the improvements that the workers building the museum are now benefiting from, given the better wages, sanitary facilities, even the establishment of recreational areas in the segregated camp, given the hard work it takes to mobilize a boycott and to negotiate with the Guggenheim Foundation and the TDIC—but how can we suppress our reflex to be so utterly disgusted by the meager alms offered in this so thoroughly brutal environment, by the knee-jerk diplomatic affirmation of avarice, and especially by these blueprints for the good life in a panopticon for workers that reflects mainly one thing: World-Class Culture itself?

This World-Class Culture is not something remote, but part of these fingers that glide so easily across the keys, on the second floor in Berlin, typing out ‘antagonism.’ But don’t we have to keep on writing anyway, so that this possibility does not cease to exist?

Translated by Jennifer Taylor

1 Human Rights Watch, “The Island of Happiness”: Exploitation of Migrant Workers on Saadiyat Island, Abu Dhabi (2009); http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/uae0509webwcover_4.pdf.

2 Alice Creischer/Andreas Siekmann, “Der Universalismus in der Kunst und die Kunst des Universalismus,” in: springerin 3/2008, pp. 34–38.

3 Human Rights Watch, Building Towers, Cheating Workers: Exploitation of Migrant Construction Workers in the United Arab Emirates (2006); http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/uae1106webwcover.pdf.

4 Human Rights Watch, The Island of Happiness Revisited: A Progress Report on Institutional Commitments to Address Abuses of Migrant Workers on Abu Dhabi’s Saadiyat Island (2012); https://www.hrw.org/reports/2012/03/21/island-happiness-revisited-0.

5 Gulf Labor, “Who’s Building the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi?” Timeline; http://gulflabor.org/timeline/.

6 “A one year campaign starting in October 2013. Artists, writers, and activists from different cities and countries are invited to contribute a work, a text, or action each week that relates to or highlights the coercive recruitment, and deplorable living and working conditions of migrant laborers in Abu Dhabi …”; cf. http://gulflabor.org/2013/gulf-labor-launches-52-weeks-of-gulf-labor/.

7 Bern: Besetzung von PricewaterhouseCoopers; http://de.indymedia.org/2002/02/14708.shtml.

8 Human Rights Watch, The Island of Happiness Revisited.

9 “The United Arab Emirates has confirmed hiring a company headed by Erik Prince, the billionaire founder of the military firm Blackwater. According to the New York Times, the UAE secretly signed a $529 million contract with Prince’s new company, Reflex Responses, to put together an 800-member battalion of foreign mercenaries. The troops could be deployed if foreign guest workers stage revolts in labor camps, or if the UAE regime were challenged by pro-democracy protests like those sweeping the Arab world.” http://www.democracynow.org/2011/5/18/jeremy_scahill_on_blackwater_founder_erik.

10 David Batty, Guggenheim delay raises big question: is Abu Dhabi ready for modern art?; http://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/apr/17/abu-dhabi-guggenheim-delay-question.

11 Colectivo Situaciones, Über den forschenden Militanten (2003); http://eipcp.net/transversal/0406/colectivosituaciones/en.

12 On Neoliberalism: An Interview with David Harvey by Sasha Lilley; http://mrzine.monthlyreview.org/2006/lilley190606.html.

13 Gulf Labor, Oberservations and Recommendations, March 2014; http://gulflabor.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/GL_Report_Apr30.pdf.