Issue 4/2015 - Kiev, Moscow and Beyond

Playing at Politics, Learning to Speak

Documentary Theater by Kyiv’s TanzLaboratorium Experiments with Forms of Commonality

“We are the same kind of people as you!” cried one woman from the stage in Mariupol, replying to the frustrated criticism of an audience member. “You could have been here!” she said, indicating that their positions on either side of the “fourth wall” were interchangeable, determined not by special privilege or expertise, but almost arbitrary, based on voluntary response to an open call. The performance of the documentary theater project Expertyza in Mariupol last spring ended with the audience physically splitting along two sides of the auditorium – those who considered the experimental performance a complete “bomb,” and those who did not. This argument that ensued at the close of the show was already integrated into the work's structure: each performance ends with a period when audience members are invited to pose questions to the participants on stage. It highlighted the conflict between the social and political; between audience expectations that theater should “do something to them” in exchange for a ticket purchased and “emancipated spectatorship,” where the audience is offered a common experience to consider from individual positions; between teaching another person how to do something “right” according to what you know and provoking someone else to think more deeply by taking an interest in his/her words and offering your own questions.

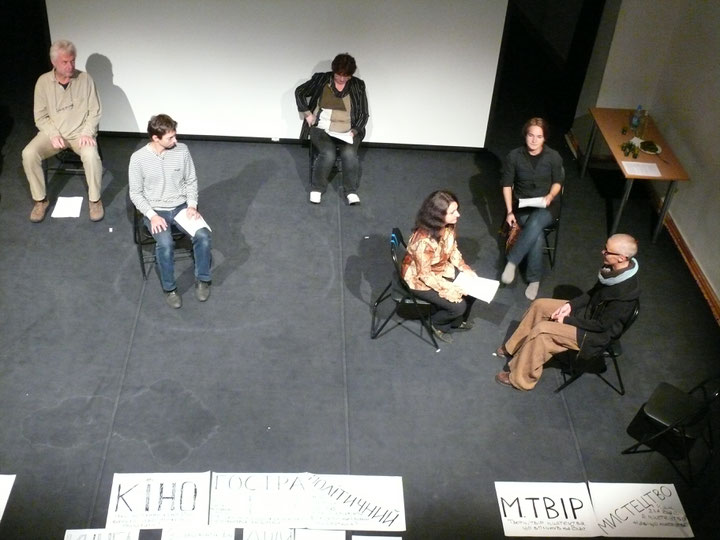

Kyiv-based performance group TanzLaboratorium has been repeating the documentary theater work Expertyza (a Ukrainian word meaning “expert analysis”) in different sites (a traditional black-box theater, army bases, museums, a church, etc.) since spring 2013. The project began at Les Kurbas National Theater Arts Center at a time when its employees were divided over the institution's future – as a way for them to get to know one another both on the personal level (what do you like to eat for breakfast?), as colleagues (how do you envision the institution you would like to work in?), and as citizens (what form of government do you consider most agreeable?). Expertyza uses simple but precise rules to organize a discussion among voluntary participants, who perform as “experts” of their own life experience. Eschewing the customary artifice used to represent reality on stage, these “rules of the game” create a sliver of space-time that allows one to examine autonomous elements and events as separate things. Members of an institution, community or social category become visible as individual people; the words spoken appear as objects for analysis on stage and afterward. Evolving together with the changing social and political situation in Ukraine, the project has expanded to address a variety of pressing issues (including the Maidan protests, cultural policy, war and peace, discipline, internally displaced persons and refugees). Since 2015, the artists have been traveling to towns all over Ukraine, including those along the border with the territory now occupied by the Russian army and Russia-supported local militias, and have sought to initiate conversations with and among local residents.

Recent performances have revealed that many people do not envision a world that allows for difference, or for anything that is not already accounted for in their existing worldview. (Perhaps this is one of the reasons that the Maidan protests – which unleashed new kinds of cooperation and coexistence that defied my own capacity to describe or conceptualize them as they were emerging in action – were so quickly relegated to memory and official commemoration as a historical event rather than as transforming ongoing political processes.) Participants in all parts of Ukraine have repeatedly referred to others who are different from them as in need of correction, as potential members of society on the condition that they change their views or practices to align with the values of the speaker, or as “not normal.”

In a village in the Carpathian Mountains, in western Ukraine, the conversation reached an impasse when one man declared that Ukrainians could unite only once everyone embraced the Christian faith. His conversation partner asked how they could live in the same society if his view did not allow for anyone other than Christians. Rather than considering a society where people do not impose their religious views on one another, he preferred to put off thinking about how Ukrainians could live together until religious unity was achieved. In Mariupol, under the auspices of Expertyza, a discussion without a formal audience was organized with female university students. When the question of single-sex romantic love was raised, the girl speaking said, “That’s not right.” To the question “Why not?” she replied, “I don’t understand how that can be!” Her words revealed an all too prevalent logic that equates “I don’t understand” with “it’s not right.” Rather than letting the other be (with his/her specific religion, worldview, sexual practices, behavior, etc.), thus creating a more complex picture of our shared world, people persistently demand that others conform to their own standards of behavior or beliefs before acknowledging the presence of another person as an equal in the same society, nation, community, etc.

Expertyza presents an idea of a “common ground” that differs from modern-day notions of identity, solidarity, or cooperation for the sake of a particular goal, which are predominant modes of social organization. Rather, it revives the tradition of the “public realm,” as understood and practiced in the ancient Greek polis. Distinct from the private sphere (where questions of survival were managed), the public realm is where a person appears before others – his peers – all equally free in speech and action. Hannah Arendt writes “the reality of the public realm relies on the simultaneous presence of innumerable perspectives and aspects in which the common world presents itself and for which no common measurement or denominator can ever be devised … Only where things can be seen by many in a variety of aspects without changing their identity, so that those who are gathered around them know they see sameness in utter diversity, can worldly reality truly and reliably appear.”1 TL's documentary theater stages an artificial, temporary public realm that shows us ourselves as cohabitants of a common world. It exposes not only how and about what we speak, but also how we interact with one another, including the inability to speak or listen or establish a connection with the present moment shared by all in the theater.

Politics, as understood and practiced by the ancient Greeks, namely as the process of human speech and action directed at a common world beyond the perpetuation of the species, has all but been forgotten in today's world. The ongoing crisis in Ukraine is but one example of the widespread inability of contemporary people to cohabit a common world as seen from their different positions. Over the brief period that Maidan in Kyiv was occupied by protestors, a time characterized by the constant threat of violence and uncertainty about what might happen next, conversations among strangers sprouted up organically out of curiosity toward one's neighbor or the desire to share one's thoughts about what was going on in this incomprehensible situation, often leading to energetic debates on the future of Ukraine, the problems and obstacles it faces. People learned from and about one another as they warmed themselves by makeshift fires, but when attempts were made to organize small groups to articulate common positions or plans of action, this kind of “grassroots politics” did not get very far. After the tragic deaths of over a hundred of those protestors, their public canonization as national heroes, and the return of the square to its previous state, it looks like that brief outpouring of public speech was a localized anomaly.

Today the majority of Ukrainians still demonstrate a culturally conditioned inability to speak: to say with their own words what they themselves think. Formed by a history of Soviet repression – those who spoke their minds or expressed individual thoughts were liquidated, and those that remained alive were discouraged from any kind of behavior deviating from the norm – they have inherited a culture based on fear and mistrust of the other, as well as an absence of a public space for individual expression. Speech needs to be practiced – it exists only in the moment of enactment, and its potential for endurance depends on its capacity to affect the common world. Unlike society at large, which encourages normalized behavior and modes of expression, TL's documentary theater offers a space for speech as singular public action. According to the project’s introductory text, “The theater creates the possibility to begin a conversation. Once you are onstage you are obliged to speak, for silence upholds the words of whoever is speaking. When someone starts speaking, s/he appears, making it possible to defend one's position, to continue the discussion.”

In this sense, the participants of any given production of Expertyza are “playing at politics.” Playing a game means accepting certain rules for the duration of the game as common conventions shared by all participants. Yet it also implies the possibility of “playing around” – experimenting with approaches or tactics allowed by the given situation or even bending the rules, and seeing what happens. Taking part in a production means bearing responsibility for the entire situation, though one can neither predict nor control what will happen: each participant is free to act when and how s/he decides. The “rules of the game” devised by the artists take on an authority that no one involved in the production can claim.

TL's documentary theater has no director; the onstage action progresses without a script or ultimate goal. The conversation is structured around questions written by the participants themselves, related to the topic announced by TL. Discussion begins when anyone on stage picks up and reads one of the questions (lying on the floor and visible to participants and audience alike); likewise, anyone on stage can choose to respond to the given question (though no one must). What happens in the theater (including what does not) depends largely on how participants choose to play the game. It is up to each speaker to decide when to speak and what to say, informed by his/her own sensitivity to the whole situation and perhaps accompanied by reflections as to what motivates his/her own speech. As the architecture of a temporary realized public realm, the rules are not meant to protect any individual from taking offense, getting bored or frustrated, being interrupted or ignored. The documentary theater has no mission to entertain or satisfy the spectator, nor to teach him/her anything or transmit a message; it merely creates conditions that make it possible to see something – a process of establishing a common world (albeit inconclusive and bounded by the time and space of an evening in the theater) – in action, something that is being done not for us but in front of us, even with us. The anxiety that arises when everyone does not know what will happen next produces a tension shared by audience and participants alike.

One of the definitive qualities of the public realm in ancient Greece was its permanence, its ability to withstand the mortality of human life. Such a public realm has long been replaced by contemporary society's devotion to the perpetuation of economic interests and human life. But it makes me think about a different kind of permanence – one that lacks a physical foundation but endures through persistence and repetition. The principle of equality becomes a starting point for any human interaction, where both I and the other person have equal potential to perform a heroic act, equal potential toward evil or good, equal freedom to think and to act, and equal prospects of dying.

Translated by Helen Ferguson