To understand spirits, of the times and otherwise, you sometimes need to ask them for help. So here I must invoke one of my favorite spectral entities, a teaching spirit that I first encountered over thirty years ago, and that has been guiding me ever since. Early in Gravity’s Rainbow—itself a literary avatar of the early seventies weird—the ghost of the Weimar politician Walter Rathenau appears at Berlin seance held in the late years of the Republic. In a speech dense with chemical and occult lore, which was appropriate given all the Nazi industrialists gathered around the table, Rathenau suggests that only an uncanny hermeneutics can unpack the foreboding signs that describe the large shapes of modernity:

“These signs are real. They are also symptoms of a process. The process follows the same form, the same structure. To apprehend it you will follow the signs. All talk of cause and effect is secular history, and secular history is a diversionary tactic. Useful to you, gentlemen, but no longer so to us here. If you want the truth—I know I presume—you must look into the technology of these matters. Even into the hearts of certain molecules...You must ask two questions. First, what is the real nature of synthesis? And then: what is the real nature of control?”1

To seek the truth, here in Rathenau’s esoteric light, is to sidestep the cause and effect of linear history—the “uncanny methodology” Miller described earlier. It is to risk the occult apprenticeship of signs, signs that must be followed, just to see where they go, and what they do. But dodging secular history, here, does not mean avoiding technology—which means that technology is not secular, or at least not entirely secular. Rather, it too can be an esoteric power. Rathenau’s two questions, then, are at once industrial, spiritual, and methodological. What is the nature of synthesis—that is, what does it mean to fuse heterogenous materials into figures of the real, to forge simulacra, to connect this and that? Second, there is the even more important question of control. What is human agency in the face of social programming, cognitive scripts, and whatever nameless forces push and pull through and as the unconscious? And what crowns the hierarchy of control that steers ecologies, cybernetic systems, and other technocultural loop-de-loops? What power, in the end, is in charge?

These are the core questions of the postwar era, which is why Pynchon set his novel when he did, so near the births of LSD, the CIA, and the UFO. But these questions landed particularly hard in the seventies, when Rathenau’s directives were first channeled into fiction, and when the network effects of postwar cybernetics moved into the emerging consciousness culture that merged in the wake of the sixties. So, let’s heed our ghost’s call and take a final glance at the technology of these matters—and particularly at those seventies technologies that shaped, or suggested, new and charismatic patterns of consciousness and communication.

Lo, the Network

So what do we see when we heed Rathenau’s advice and look into the technologies of synthesis and control in seventies America? In his cultural history of the decade, Stephen Paul Miller analyzes the era in terms of surveillance, whose growth principally depended on the spread of new technologies. The conspiratorial politics that fed the paranoia on display in films like The Conversation and The Parallax View (both 1974) was mirrored by new forms of consumer surveillance and technologies that wove the body more tightly into circuits of scanning and tracking.2 The spread of the new UPC symbols made the consumer market more transparent to itself, but also sparked apocalyptic Christian fantasies about the “mark of the beast” mentioned in Revelation 13. Indeed, the best-selling nonfiction book of the decade, the evangelist Hal Lindsey’s The Late, Great Planet Earth (1970), issue apocalyptic warnings about “the worldwide computer banking system” and the spread of “in-home computers.”

Older technologies also had a prophetic role to play. The seventies were also what historian Stephanie Slocum-Schaffer calls “the high point of television’s preeminence in American culture.”3 Achieving a near total penetration of American homes, TV became at once the most popular source of news and the new home of God, as televangelists like Jim Bakker sought to create “God’s television.” Paddy Chayefsky’s scathing 1976 film Network skewered news media conglomerations during the era, while also showing a glimpse into the conspiratorial fat-cat boardrooms that lurked behind the programming of the era’s media culture. As with the UPC symbol, visible media power was always shadowed in paranoid mythologies of control and the sacred.

In retrospect, however, perhaps the most significant thing about the TV networks of the seventies is not the ubiquity of the boob tube but the idea and form of the network itself: an archetype of organization and communication that, in the seventies, inscribed itself simultaneously into material technologies, information systems, edgy subcultures, and novel expressions of the spiritual (and psychedelic) imagination. And ground zero of the network archetype was California, where consciousness culture and epochal technological innovations not only mobilized “network effect” but made the network a central paradigm of historical transformation, or what Terence McKenna would have called a novelty wave.

Modern information technologies had been around for a long time, of course, arguably since Samuel Morse developed the telegraph in 1844. They emerged in force following the mighty churn of innovation that characterized America during World War II, when communication, control, and computers were brought together into a new assemblage whose name—cybernetics—became the foundation for much of the social science and institutional power of the postwar era. The sixties counterculture is also unimaginable without its technological novelties, like FM radio, multitrack studios, and analog synthesizers. But something happened in the seventies. As the sociologist Manuel Castells argues in his classic book The Rise of the Network Society, “Only in the 1970s did new information technologies diffuse widely, accelerating their synergistic development and converging into a new paradigm.”4

Part of this diffusion involved the emergence of small “personal” computers, which individualized the machine and its users.5 But stand-alone computers were less important to the network society than the powers and possibilities that emerged when those machines became linked together. The first electronic switch came out of Bell Labs in 1969, the same year that the first message was sent on the ARPANET, the forerunner of the Internet. The text of that first message, which winged its packet-switched way between UCLA and the Stanford Research Institute around Halloween, was “login.” Because of a network failure, however, the only thing that arrived at SRI was the curious syllable “lo.” If we recall the first message that Sam Morse sent through his telegraph in 1844—"What hath God wrought”—we might say that the first message of the ARPANET was a similarly amazed but confused annunciation. “Lo!”: something is happening here, but we don’t know what it is.

By the mid-seventies, improved networking technologies like digital switches encouraged the growing complexity of the ARPANET. Even more important was TCP/IP, a network protocol invented by a couple of ARPA researchers at SRI. Rather than concentrating on connecting individual computers, TCP/IP allowed different networks to network—or “internetwork”—together. In 1976, in a characteristically Californian juxtaposition of high craft and low brow, the SRI team successfully demonstrated TCP/IP by connecting the ARPANET to a mobile high-tech Packet Radio Van that was parked next to a well-known Portola Valley biker bar. TCP/IP was eventually adopted as the central protocol of the ARPANET, and the Internet was born.

As Castells tells the story, the network was not just a new way to organize information technology. It is also a new way to organize society, which means consciousness and culture as well. In addition to its specific technical capacities, including its ability to manage globalization—or what both Marshall McLuhan and Philip K. Dick called “planetization”—the network society also included “a new way of producing, communicating, managing, and living.”6 Castells traces the emergence of the network society to the United States, and especially California, whose ethos of creative freedom, individual innovation, and entrepreneurialism fed the new social paradigm. But while some of these values were rooted in California’s history of industrial development, research universities, and public-private partnerships, many were also tied to the countercultural mores that, as many historians have shown, pervaded the technology scenes in the Bay Area from the sixties through the nineties.7 This lent the information revolution what Castells calls a “California inclination,” one that “half-consciously diffused through the material culture of our societies the libertarian spirit that flourished” in the sixties.8

One technical consequence of this libertarian spirit is the preference for open, horizontal networks over closed vertical hierarchies.9 This same distinction also helps make sense of shifts in consciousness and culture that embrace novelty, juxtaposition, and a flattening and scrambling of traditions. And there are other aspects of the network society that, as Castells describes it, resonate with some of the esoteric motifs we have tracked in this book. One is that information becomes a thing-in-itself, an almost metaphysical substance that, through its technological instantiation in networks, massively shapes both individual and collective existence. The morphology of this “networking logic” supports the growth of complexity, of new connections, of flexible operations, and unpredictable patterns of development.

Castells also recognizes the crucial connection between network logic and constructivist ideas, as well as the relativism such reflexivity opens up. As he explains, the power of “complexity thinking” derives from “acknowledging the self-organizing character of nature and of society. Not that there are no rules, but that rules are created, and changed, in a relentless process of deliberate actions and unique interactions.”10 The point here is less that constructivism is true than that it becomes an operational logic of the emerging paradigm. As Mark Taylor argues, networks create “complex self-organizing systems” that are intrinsically unstable, restless, and metamorphic. This creative turbulence can be traced in part to the reflexivity of such systems, which produce themselves through their own self-reference. In almost science-fictional terms, Taylor describes the information revolution as “something like an orbital movement in which information revolves in such a way that it begins to act on itself.”11 This self-reflexive turn is precisely the revolution of the information revolution, the positive feedback loop that bootstraps new realities out of twists in data.

Whether understood as cybernetics, human ecology, media theory, or first- and second-order systems thinking, the complex and abstract behavior of networks, systems, and information ecologies forms the implacable technological background of postwar consciousness and culture. It is also, loosely speaking, a philosophical framework shared by Terence McKenna, Robert Anton Wilson, and Philip K. Dick, the subjects of my book, all of whom shared an interest in cybernetics, information metaphysics, Whole Earth systems mysticism, and McLuhanesque media speculation. But the behavior of self-organizing systems also helps us understand the constructive, autopoetic dynamics of those weird networks that lose the sort of visionary beings that have populated this text.

For it may be that we (post)humans too are best seen as systems—observing systems, to be exact. And in the words of Bruce Clarke, a theorist and historian of “systems countercultures,” such observing systems have no choice but to “bootstrap virtual foundations out of circular operations.” In a sense, bootstrapping virtual realities—which found themselves—is what this text has explored. The paradox of these circular operations is that they are simultaneously open to novelty and closed within the circuits of their own self-reference, and this paradox that “infects any and all cognitions.” In order to operate at all, we must behave a bit like Philip Dick does as he speculates his way through the Exegesis, transforming paradox and contradiction into fuel for the next twist. “Observing systems must elicit and resolve these cognitive issues, bootstrapping themselves out of momentary resolutions of paradox that, always leading to others, keep the system stumbling forward.”12

Clarke links this neocybernetic vision of hybrid networks directly to “the daemonic landscapes of metamorphic narratives.”13 These are narratives, very much like Philip K. Dick’s, that slip their own diegetic gears, that twist into metafictional mise-en-abîmes, that mutate their own paradoxical forms. But as we have seen, such metamorphic narratives are hardly confined to fiction, which is perhaps another way of saying that fictions themselves are not confined to fiction—especially when such fictions invoke the daemonic. As I hope to have shown, the weird juxtapositions and reflexive ironies of such metamorphic narratives are also embedded within the text and texture of visionary experience in the seventies—and especially in those post-religious visions that prophetically and symptomatically ride the forward frothing edge of California’s network paradigm.

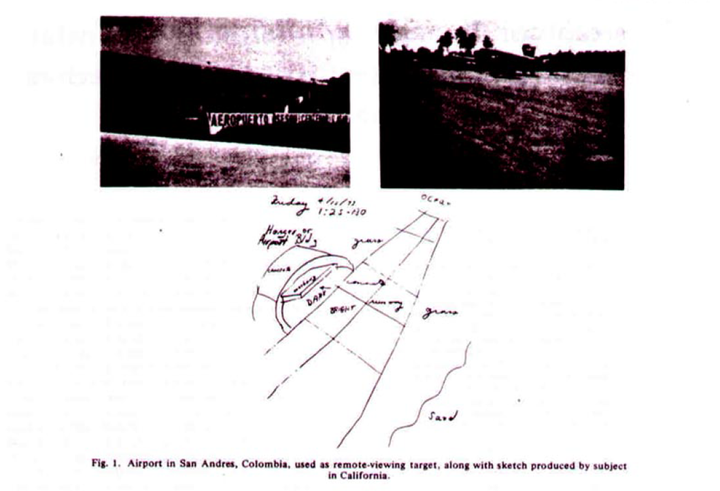

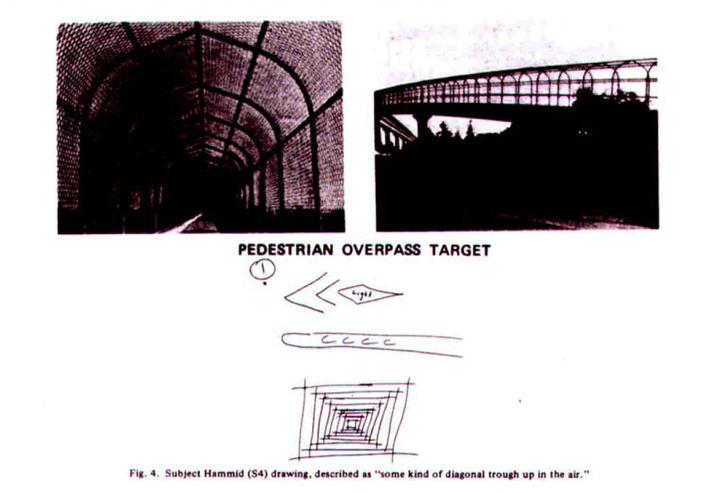

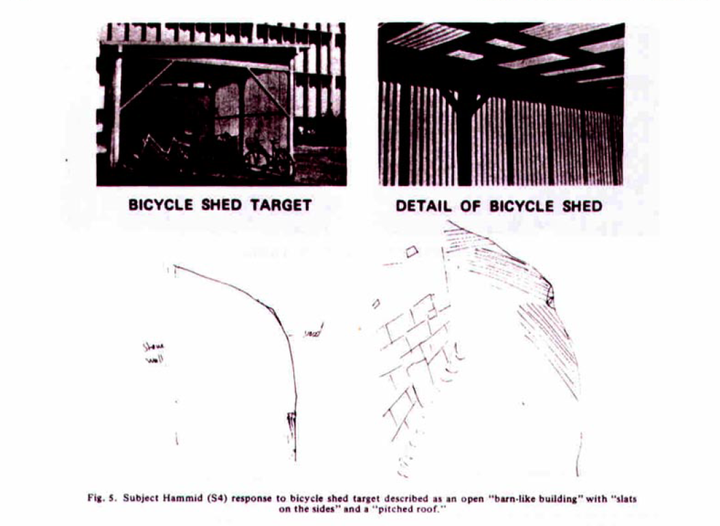

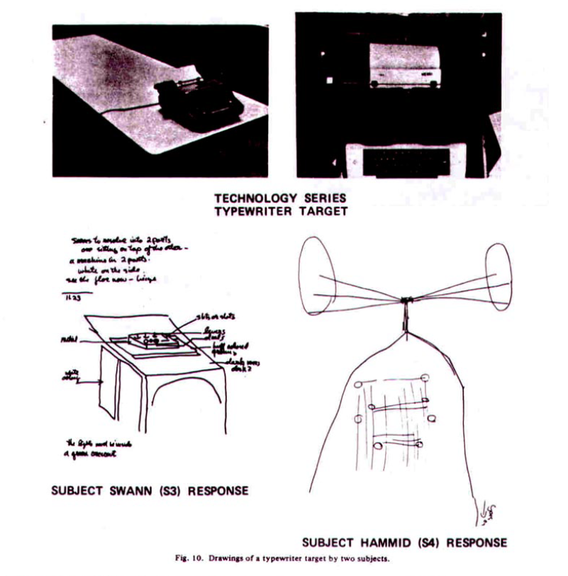

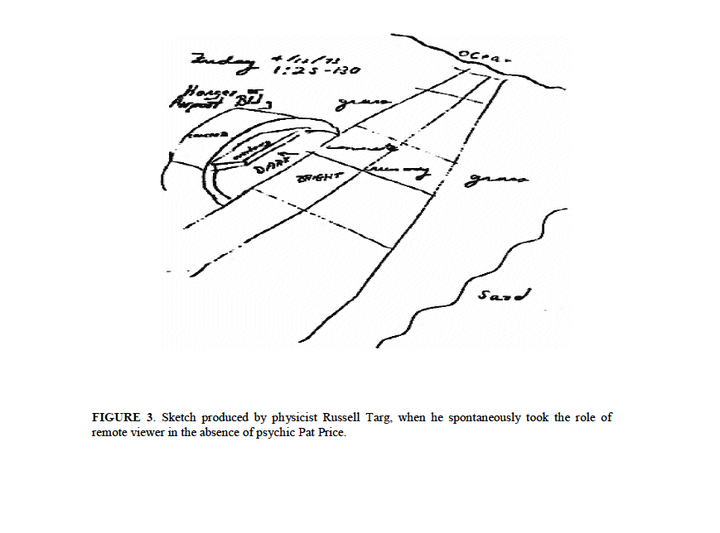

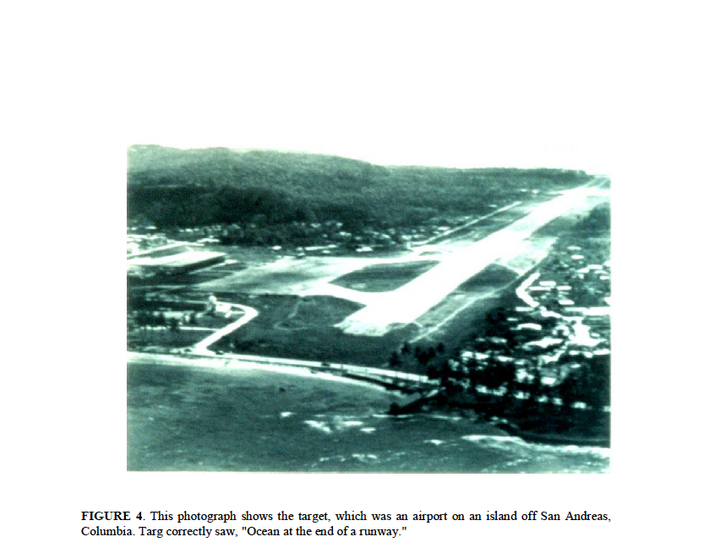

However, the futuristic sheen of the network society is inseparable from more shadowy and daemonic depths. For instance, while working on PLANET, astronomer and computer scientist Jacques Vallee was also informally involved with another research project at SRI: Hal Puthoff and Russell Targ’s notorious parapsychological research into remote viewing. Inspired in part by the specter of advanced Soviet psychic research, the CIA-funded program, which eventually evolved into the Stargate Project, attempted to weaponize ESP for the purposes of military intelligence. Gifted psychics, like the famed Ingo Swann, were directed to use their mind power to remotely peer into Soviet military bases and other distant locations. While the value of this research remains controversial—surprise, surprise—a number of outside observers have concluded that at least some of the individuals involved—like Swann and Pat Price—demonstrated a statistically significant number of hits.14

One problem the project faced was the question of how to direct remote viewers to the correct target. As physicists and engineers, Targ and Puthoff considered the problem in terms of signal transmission, but in conversations with Swann, Vallee suggested it might be better to think of the addressing problem as an issue of information science. Vallee described various ways of handling data in computer memory, especially the technique of virtual addressing. This conversation inspired Swan to develop the method of coordinate remote viewing, in which viewers are directed to their targets through geographical coordinates alone. This technique remains the standard in today’s surprisingly robust remote viewing scene.

While the historical import of this sort of innovation may seem useless to committed ESP skeptics, Swann’s coordinate system provides a direct symptom of the secret—or esoteric—traffic between consciousness culture, information networks, and weaponized paranormal power. As Jacques Vallee described the situation at SRI decades later, “There were many people researching the interface between consciousness and computers, with DARPA funding. The whole idea of consciousness and its role in physics, and its role in equipment, was very important.”15

After Vallee left SRI, he continued to work on computer conferencing systems. Analyzing the transcripts of users, he reported regularly finding strange coincidences, like people sending messages that answered questions a few seconds before the questions themselves were sent through the network. Users also described “feeling, not being out-of-body, but a sense of community when they were sharing the computer space with other people.”16 Eventually, remote viewing experiments were performed through the conferencing network, though this research—which included Jonathan Livingston Seagull author Richard Bach along with Puthoff and Swann—may have provided less light than the title of one paper Vallee published in The Futurist in 1975: “Computer Conferencing: an Altered State of Communication.”

Vallee’s work at SRI, as well as his peculiar social network—which included occultists like Wilson and the Satanist Anton LeVey alongside all manner of UFO researchers and freethinkers—reminds us that weirdness was not restricted to bohemia, but reached its tendrils deep into Bay Area research institutions, think tanks, and technology firms. The occult revival was hardly limited to the freaks. While Puthoff and Targ were both accomplished physicists, Puthoff was also a high-ranking Scientologist, as was Ingo Swann. Even Engelbart, who invented the computer mouse and digital groupware, became heavily involved with Werner Erhard’s “est” program in the seventies.

Two decades before the mass blooming of the Internet in the nineties, computer networks were already linking code and consciousness, subcultures and subroutines, altered states and information politics. To see this as esoteric trivia is to miss the depths of the network transformation that—however muddled the metaphysics, and however compromised the political economy—characterized the era. As Felix Guattari reminds us, “technological machines of information and communication operate at the heart of human subjectivity, not only within its memory and intelligence, but within its sensibility, affects and unconscious fantasms.”17 It is this phantasmic heart of technological subjectivity that McKenna, Wilson, and Dick plumbed and mapped with their daemonic prophecies. Like poets and artists, such psychonauts are the “antennae of the race,” and what they tune into, at least some of the time, are the shapes and patterns of the Zeitgeist. High weirdness, in this laser light, looks a lot like the anxious precognition of the emerging network society and the Pandora’s box it would boot up.

1 Thomas Pynchon, Gravity’s Rainbow (New York: Viking Press, 1973), 167. For a particularly astute reading of this passage, see Alan Jacobs, “Text Patterns: The Rathenau Seance,” in: The New Atlantis, http://text-patterns.thenewatlantis.com/2017/04/the-rathenau-seance.html. “I am tempted to say that any theology adequate to the Anthropocene era will be an extended commentary on this passage.”

2 “Credit checks became more centralized. Governmental agencies first used tools such as computer matching to cross-reference computer files, thereby identifying inconsistencies and finding lawbreakers … Perhaps most importantly, the silent majority as well as consumer-culture dropouts were canvassed and enlisted in the increasingly centralized marketplace.” Stephen Paul Miller, Seventies Now (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1999), 3. At the same time, humans bodies were revealed in new ways through CAT scans—invented in 1972—while ultrasound and magnetic imaging technologies became widely available in hospitals.

3 Stephanie Slocum-Schaffer, America in the Seventies (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 2003), 179.

4 Manuel Castells, The Rise of the Network Society. The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture, Volume 1 (Malden, Mass: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), 39.

5 The microprocessor was invented in Silicon Valley in 1971, and such integrated circuitry paved the way for smaller machines. In 1973, Xerox PARC developed the Alto computer, which became the unintentional prototype of the first Apple, though it was the Altair 8800—developed, admittedly, in New Mexico—that was proclaimed the first “personal computer” in 1975. At Atari, microprocessors also fueled the emergence of the video game and home console, and the myriad of algorithmic pocket worlds that emerged.

6 Castells, The Rise of the Network Society, 5.

7 Steven Levy, Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution (New York: Dell, 1984); Fred Turner, From Counterculture to Cyberculture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008); John Markoff, What the Dormouse Said: How the Sixties Counterculture Shaped the Personal Computer Industry (New York: Penguin Books, 2006); Bruce Clarke, “From Information to Cognition: the Systems Counterculture, Heinz von Foerster’s Pedagogy, and Second-Order Cybernetics,” in: Constructivist Foundations 7, no. 3, 196–207; Adam Fisher, Valley of Genius: The Uncensored History of Silicon Valley, As Told by the Hackers, Founders, and Freaks Who Made It Boom (New York: Grand Central Publishing, 2018).

8 Castells, The Rise of the Network Society, 61, 6.

9 “The information technology paradigm does not evolve toward its closure as a system, but toward its openness as a multi-edged network.” Castells, The Rise of the Network Society, 75–76.

10 Ibid., 74.

11 Mark C. Taylor, The Moment of Complexity: Emerging Network Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), 78.

12 Bruce Clarke, Posthuman Metamorphosis: Narrative and Systems (New York: Fordham University Press, 2008), 64.

13 Ibid., 45.

14 The literature on remote viewing is quite large. For an early historical overview, see Jim Schnabel, Remote Viewers: The Secret History of America’s Psychic Spies (New York: Dell, 1997).

15 Jacques Vallee, “The Software of Consciousness,” Lecture, International Remote Viewing Association, Las Vegas, NV, 2007; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=40jqdrEVPX4

16 Ibid.

17 Félix Guattari, Chaosmosis: An Ethico-aesthetic Paradigm (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1995), 4.