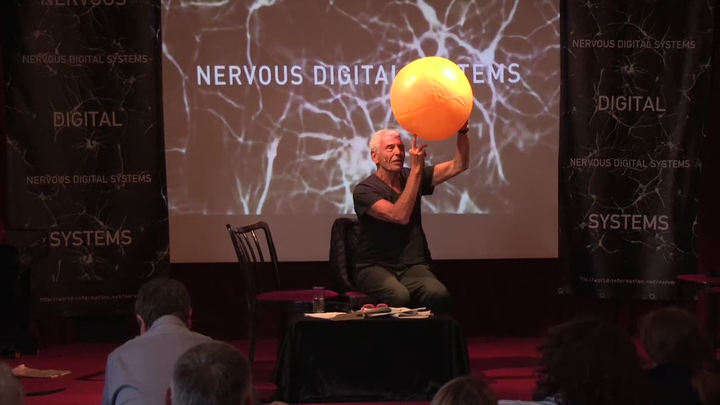

Michael Taussig, anthropologist and cultural theorist, reflects on the boundaries and affective connections between bodies and objects. An important figure in this, as he was already for Walter Benjamin, is Enrico Rastelli (1896–1931), the most famous juggler of his time who could handle balls as if they had a life of their own. This conversation was conducted by El Iblis Shah in the context of Michael Taussig’s presentation “Rastelli, The Juggler, or What Are the Turks Doing in Walter Benjamin’s Theses on History and the Bodily Unconscious”, part of “Nervous Digital Systems” which took place on May 29, 2019 in the Roter Salon of Vienna's Volkstheater.1

On Lively Objects and Animated Things

Wolfgang von Kempelen’s chess playing Turk is 18th century, so this artificial intelligence idea is not so new. My interest is in the way in which changes such as climate change, affect the bodily unconscious, of human beings in particular, but of all of nature. They create or affirm hypertrophic (in the sense of unusually expanded) connections between bodies. You could call them “things” or call them “bodies”. Body sounds more “organic” and full of life, animate, if you like. This sort of animation is a key way of thinking about the changes that will affect us all, that, as with global warming, have to do with the unconscious intelligence of the body as it is affected by the myriad changes in environment.

In the relationship between the juggler Rastelli and the ball, the animation is seen as a trick.2 And it is that aspect of animation, of lively objects that appeals to me. They do involve an element of trickery, pulling the wool over the eyes of a willing audience, which could be the electorate, it could be a social media audience, whatever, small or huge. That trickery is what interests me about a new understanding of animation and a new object philosophy. But it’s not the object per se. Whilst the object-oriented philosophy people are interested in dehumanizing humans and objects, my instinctual approach is to turn that around 180 degrees. To humanize, or animate, the object; as in fairy stories in which objects become alive so miraculously, and to understand this process of animation seems to me very important, philosophically and politically.

On the Logic of Faith and Skepticism

It seems to me logically impeccable that faith assumes skepticism. That’s at the level of logic, let alone empirical reality. When people who believe fervently in a saint, a shaman or something invisible, when they speak, you always see this oscillating wave of believe and disbelieve, disbelief producing belief, again and again. It was put very well in 1937 by the Oxford anthropologist Edward E. Evans-Pritchard who pointed out that faith and skepticism go hand in hand with magic.

If you try to understand the worlds of beliefs, including ideology, Foucault’s discourses, counter-discourse and so forth, and see them as unidimensional and overlook this dynamic mix, of faith and skepticism as moving hand in hand, you lose, you relinquish, you sell out the capacity for attack, for counter-attack. It is only if you realize that this mix is occurring – for example amongst Trump supporters and himself – you realize that it opens up a vantage point for leverage to say something like the opposite. I think someone like Trump – whether he is clever or stupid I don’t know – more or less unconsciously he is aware of that and he is using it himself. This is a beautiful instance of mastery of non-mastery, because it provides a countervailing force which is then picked up by the force that it is attacking…

The Mimetic Faculty and the Metamorphic Sublime

The way I see it is that the mimetic faculty assumes a gift relationship between two parties, at least two parties, which could be a person and an animal, a person and mountain, a person and a drawing, a person and an idea and it’s a reciprocal relationship. You could apply Marcel Mauss’s lectures on the gift to the mimetic faculty. I have never seen anybody do that, Benjamin doesn’t include that for example in his famous three pages on the mimetic faculty. But if you would do this, you would see that this relationship is a gift relationship and not a commodified relationship. Then, it seems to me, you understand that the world can only be saved – if saved at all – through a reciprocating tenderness and mutual understanding. So for me that is a key component of the mimetic faculty. Weighing heavily, if not completely, on strategy and tactics. So the mimetic faculty is not simply the kid becoming a windmill, it’s an understanding of reciprocating back and forth between that windmill and that kid.

So that is where I would put my emphasis when defining the mimetic faculty. This applies, I would say, to technological advancement or change, to social media, to politics, to what I called Trumpism as global tendency, if not the mainstream of politics; including the politics of the family, politics of the factory, politics of a nation state and politics of the modern world. This is based on and encourages mimesis. And this mimesis is of such intensity, of such a lurid imaginative capacity that involves what I call the Metamorphic Sublime. And this Metamorphic Sublime is dangerous and exciting but once again I would assume that it too involves a tenderness, an alertness of thought to the reciprocating obligations of a gift.

And that to me seems the way of getting away from the type of Metamorphic Sublimity, the type of mimetic equations that are involved in the domination of nature. I am not just dragging in this mimetic faculty from out of space; it seems to me that the domination of nature has always included its own form of mimesis. You can call it, in a sort of binary, a black and white way, an instrumental mimesis, a mimesis that is used for the power of rulers and for profit. So it’s not as if we drag in the mimetic faculty to oppose the domination of nature. It is using the mimesis that is in the domination of nature against itself. And that is where the notion of the conjurer comes in.

Discourse and the Resonance of Ideas

In that talk yesterday about Rastelli, the emphasis on the trick in the so-called Shamanism or the conjuring – conjuring is a metaphor, conjurer is a real practice – becomes so interesting. And for a person, who is concerned with writing as I am, writing becomes the field in which we use words, play with other words, and ideas more generally and some people call it communication.

It is how you understand the political discourse, what used to be call ideology. Most people I know who talk about political ideas seem to think that the idea can be reduced to some core statements. I think that’s untrue and that it is the atmosphere in tone, the resonances in which ideas are conveyed, and that is art. Skilled politicians for example know that, advertisers know that, artists know that. What is art? Art is got to be the sensitivity to the resonance of the things of the world in order to turn people into another adventure of ideas.

On Signifiers and Mapping of Territories

“The map is the territory”, yes, that would be absolutely axiomatic for me. Young professors in social sciences and linguistics like to embolden themselves and enlarge their status by telling students that the sign is unmotivated. The Saussurean, even Platonic, idea, that there is a critical gap between the word and what the word refers to. The word “cat” is not the same as the cat, and cat is different to “rat” and “mat” and so on. This is part of the theory of phonemes (basic units of sound in language). Be that as it may, I find my own practice and the way people understand the world and listen to language is totally distinct to that, or it ads to that some other heartfelt notion that, indeed there is a concrete organic connection between language and what the language signifies.

My recent book, Palma Africana3, is very much dedicated to the notion that the language not only invokes or evokes that which is being spoken about, but language merges with what it speaks about. And that’s why there is so much interest in that book in animals, in animalization you might say, that words become like animals and so forth. So the writing becomes – as I put it – what the writing is about. I think this is how we read and how we listen. And I would say that is always tagging at my writer’s elbow – it is sort of unconscious, but not completely unconscious. It is what I find exciting in ideas and in listening to people and in responding. Putting it simply, I think, human beings are interestingly strange if you point out to them the arbitrariness of the signifiers, the map not being the territory and all that sort of stuff, people will nod and say: “Ah, yeah, I get it, of course, what a fool I was.” But one fraction of a millisecond later, bang, the map is the territory again.

1 https://world-information.net/video-nervous-digital-systems-29-05-2019-2/

2 Walter Benjamin, Rastelli erzählt …, in: Neue Zürcher Zeitung, November 6, 1935.

3 University of Chicago Press 2018.