Issue 2/2020 - Net section

We Are Left with a Feeling of Nakedness

A look behind the interfaces of the tech giants with net artist Joana Moll

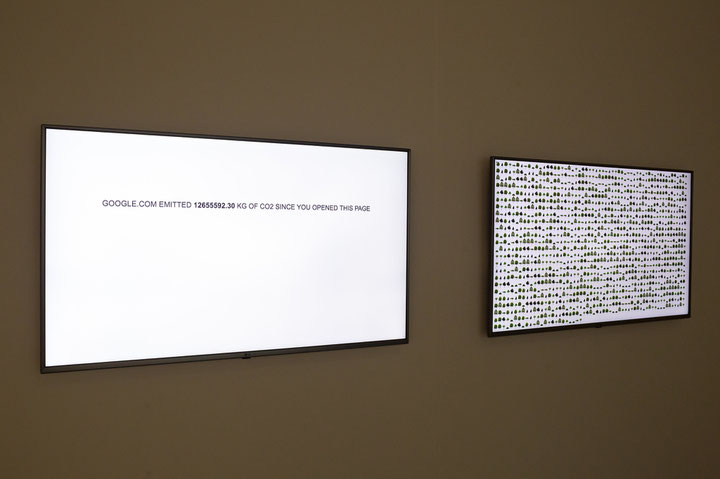

Sabine Weier: As we talk on Skype, a significant amount of CO2 is being emitted through this service. The role of the Internet in climate change is the subject of works like “DEFOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOREST” (2016)1, a net-based piece that shows the amount of trees needed to absorb the amount of CO2 generated by visits to google.com. How did this interest become a central aspect of your practice?

Joana Moll: I started to work on materiality a few years ago. I have always been interested in how things work. Staring at the screen of my computer I suddenly realized: this cannot come for free. I was shocked by how we don’t realize this connection, how it is not embedded in social imagination. The Internet consumes a massive amount of resources. By 2025 communication technology will make up 20 to 25 percent of global energy consumption. In 2008 the Internet already caused higher emissions than the aviation industry. The amount of data we are producing increases at a crazy pace. I’ve also always been interested in the relationship of nature, politics, technology, economics, patriarchy, and language. We live in a society where everything is supposed to be connected, but we are more disconnected from what is going on than ever before. In times of climate emergency, this is quite a critical state to be in.

Weier: Net art seems a natural choice as it brings together these interests. How did you come to work in this genre?

Moll: Exactly, it was the medium that allowed me to merge all these interests. The Internet is probably the biggest infrastructure that we’ve ever built. There are many different narratives embedded in this infrastructure and in the way in which we use it. With net art you can understand these narratives and, moreover, you can alter them in a speculative way.

Weier: Aesthetically, some of your works are reminiscent of early net art.

Moll: I wasn’t aware of that. Back when I was still a student we worked with flash animation and programming and I produced some works that were true net art. Net art pioneers Jodi inspired me a lot because their work showed that you can really do anything you want.

Net art can disturb the mainstream and standardized use of technology. Especially when it comes to the interface. Interfaces are the main thing we actually communicate through. We are connected through interfaces.

Weier: The economic exploitation of user data through these communication interfaces is one of the major issues of our time and the subject of your latest works. How come we don’t care about what is going on behind these interfaces?

Moll: I don’t think we don’t care. I think we are extremely overwhelmed. The system is complex and very hard to understand. For “The Dating Brokers” (2018)2, I bought one million dating profiles from the Match Group, the biggest online dating company in the world that owns platforms like Tinder and OkCupid. It cost me 136 Euros. My main question was: where did these data come from and why could I buy them so easily? The dating industry relies on the continuous flux of profiles in order to constantly have fresh faces available. That makes people buy subscriptions and increase the possibilities of finding a match. Therefore, the exchange of profiles between platforms is very common. This is something that you allow when you sign in on any of these websites. Most of the profiles I bought came from a website called PlentyOfFish, the second most used platform in the US after Tinder, also owned by Match Group. I found out that more than 200 companies related to Match Group were allowed to sell these profiles. Match Group in turn is owned by a bigger company network, also American, called InterActiveCorp. So, the number of companies and services that could potentially exploit a single profile rose to about 700. That’s massive.

Weier: Even desire is being monetized in digital capitalism. What do you think will become of human experience in the age of algorithmic governance?

Moll: There is a part of us that doesn’t belong to ourselves anymore. It has a life of its own, something we lose control over. I find this very disturbing. We accept this and can’t do much about it. But it leaves us with a feeling of nakedness. Just recebtly I uploaded photographs of my apartment in Barcelona to a home swap platform, as I travel a lot with my family and swapping apartments is convenient of course. But I felt as if some part of my intimacy had been taken away. And that is actually what happens every time you sign up for a new service. Your intimate data are being monetized by a big number of companies.

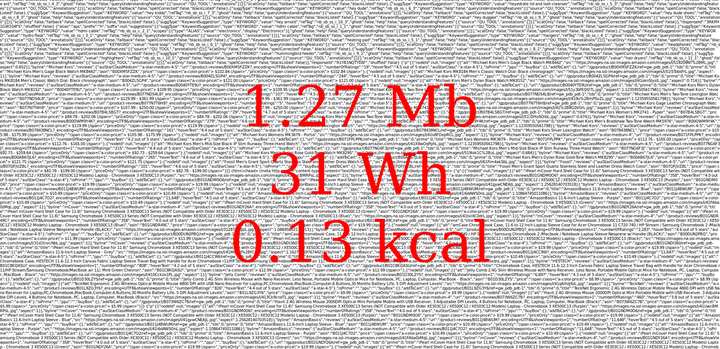

Weier: The exploitation of personal data is also the subject of “The Hidden Life of an Amazon User” (2019)3. And here, climate change comes into play again.

Moll: In this project I additionally focus on the amount of energy needed to execute this exploitation. I did the simplest purchase I could do on Amazon: I bought a book by its founder and CEO Jeff Bezos. The system made me go through twelve different interfaces which generated almost 9000 pages of code. It takes about 15 minutes to scroll down these pages. Most of the code is about tracking user activities and making users buy more. This consumes a lot of energy and is happening in your very own computer. So, we are not only exploited in terms of free labor, but also supply the energy required for being exploited.

Weier: “Arizona: move and get shot” (2011–2014), “AZ: the Archive” (2015), and “The Virtual Watchers” (2016)4 is a group of works based on a digital archive with surveillance images taken at the US-Mexican border. You have supplemented these with portraits that the watchers themselves have uploaded on Facebook.

Moll: The surveillance cameras are part of an online platform created by a group of landowners who provide the public with raw images of immigrants crossing the border. The platform is funded by the state of Texas and is aimed at outsourcing national security to civilians. You can’t tell whether the people you see on these images are from Honduras or if they are Americans. I then accessed the Facebook group in which the ones watching the border 24/7 from their homes communicated with each other. And suddenly their lives became so exposed. You learned about their families, where they lived, where they worked and so on. So, the project allowed me to find out more about the watchers than about the people watched.

Weier: Contrary to the hopes of early cyberfeminism, the Internet has enforced patriarchal structures, leaving little space for empowering action. What are your observations in this respect?

Moll: We tend to forget that the Internet was built on patriarchal ideas and ways of operating. It was built by and is still run mostly by males. The first graphic interface was created in 1963 in the US by a group of white males. Both science and technology are thoroughly patriarchal systems. The way technologies are conceptualized and operated are defined by patriarchal modes of thinking. We all use these interfaces and thereby replicate the ideas they are built on.

Weier: What are you working on currently?

Moll: Among other things, I’m working about the environmental effect of consumer online tracking. I’m interested in the role of analytics and in how the benefitting companies should be held accountable for the energy consumed.

1 http://www.janavirgin.com/CO2/DEFOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOREST_about.html

2 https://datadating.tacticaltech.org/

3 https://www.janavirgin.com/AMZ/

4 http://www.janavirgin.com/AZ/index_about.html, http://www.janavirgin.com/AZ/ARCHIVE/, http://www.virtualwatchers.de/