Issue 3/2020 - Net section

Seeding a Revolution in Art

Luiza Prado de O. Martins and Amazoner Arawak at the Transmediale 2020

For this year’s Transmediale “End to End” (28.01–01.02.2020), Berlin’s premier festival for media arts and digital culture drew on pre-internet ideas of the network to uncover potentials for sustainable social change.1 In 2019, the Berlin-based artist, scholar and designer Dr. Luiza Prado de O. Martins was awarded Transmediale’s Vilém Flusser Residency for Artistic Research. From Brazil, Prado de O. Martins draws on feminist and ‘folk’ knowledge to discuss reproduction and the control of bodies, coloniality and radical forms of care. During her residency she met with activists, artists and elders representing marginalized groups in Berlin and Brazil to develop her research to encompass “entanglements between the ongoing climate crisis, fertility, land and belonging.”2

Prado de O. Martins’ installation, For those who stand at the shoreline (2020), lifts its title from a poem by Audre Lorde3 and was part of Transmediale’s exhibition, “The Eternal Network” curated by outgoing festival director Kristoffer Gansing at Haus der Kulturen der Welt (28.01–01.03.2020). On the polished cement floor of HKW’s main exhibition space, Prado de O. Martins had placed large square red carpet, at the center of which sat a knee-high plinth or table, also painted red. On it was arranged an amorphous sculptural object resembling a splayed dried fish (one of the artist’s experiments in making bioplastic), alongside containers of seeds, seed pods and birth control pills. Cushions were scattered around the carpet and above it, hanging unevenly from the ceiling were a cluster of stretched fabric panels—hammocks actually—strung out like sails. In Brazilian Portuguese the word for hammock is rede, which indicates a net for sleeping—rede de dormir—and also a network such as the internet. Projected onto the hammocks from below was Prado de O Martins’ innovative “GIF essay” All directions at once (2018).4 Produced for a web residency at Schloss Solitude, it is an interactive net-art piece, recounting the artist’s encounters with plants, archives and the urban environment in Brazil from which the knowledges of colonized, enslaved or otherwise repressed women can be discerned.

Having spent time during the residency in Boa Vista, the capital of Roraima in the far north of Brazil, Prado de O Martins describes her research as a collective project, resulting in an installation that is a discursive space—perhaps a “conversation piece” to draw on Transmediale’s discourse5—and “a space to dream and look up, to lie down and contemplate.” These aspects of hosting and sharing experiences emphasize the idea of the network as “a social concept” rather than a digital one; a notion that Gansing proposes we revive to address the crises of our present.6 This was made most clear when the installation was “activated” during the festival week for two events, “To Seek Nows, To Breed Futures #1 & 2” for which Prado de O Martins had invited the Amazonian indigenous activist (Wapixana and Makuxi), artist and social anthropologist Amazoner Arawak. Prado de O Martins described these informal sessions as an extension of the conversations and practices that arose amongst artists, activists and researchers affiliated with the gallery founded by Makuxi artist, Jaider Esbell.7 Indeed Prado de O Martins revealed that for a period of time she lived in the Boa Vista gallery, sleeping in a hammock, where discussions circled around ideas of art and activism—"artivism.”

In her essay for the festival publication, “There are words and worlds that are truthful and true,” Prado de O Martins asks: “How is it possible to create the conditions for life within a political system designed to produce death?” It is notable that her residency with Transmediale coincided with the first year of Jair Bolsanaro’s presidency in Brazil, during which his government was accused of “widespread, systematic attacks” on indigenous groups, Black people and the poor.8

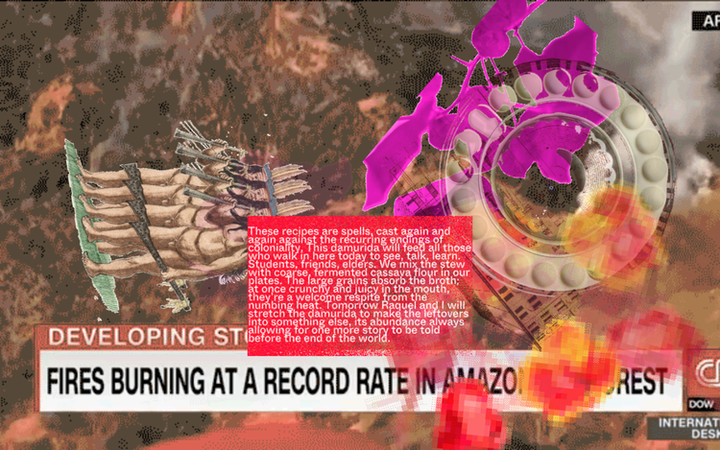

In the summer of 2019, forest fires decimated large tracts of the Amazon rainforest, with many blaming ranchers clearing the way for illegal land grabbing. For decades indigenous activists in Brazil have been the target of deadly violence, and last year saw the murder of well-known Forest Guardian Paulo Paulino Guajajara.9 Late last year a delegation of Brazilian indigenous leaders travelled to Europe to launch their campaign “Indigenous Blood, Not A Single Drop More.”10

Presently, Brazil is one of the countries most affected by the global Coronavirus pandemic, with almost 2.5 million confirmed cases and over 87, 000 deaths (as of 27 July 2020).11 Yet from its outset President Bolsanaro has downplayed its affects, flaunting measures to curb its spread and describing the pandemic as a “little flu.” This year the Brazilian Government lost two Health Ministers (Luiz Henrique Mandetta was sacked in April and his replacement Nelson Teich resigned the following month) and at the time of writing the position remains empty. Bolsanaro tested positive for Corona in July, but while Brazil’s hospitals and clinics are overwhelmed, the President has access to the best medical treatment. If he does not develop symptoms or otherwise overcomes the virus, it will undoubtable prove to Bolsanoro supporters that his claims were correct. In contrast, indigenous communities in Brazil are most vulnerable to the virus, and several notable figures have succumbed, including Jaider Esbell’s mother and Makuxi elder, Koko Meriná Eremu, who died in June, aged 75.12

Arawak began his discussions at Transmediale by holding up a small seed, Urucum (Bixa orellana), proposing that it be considered a technology. Used by indigenous people for food and body paint, it was traded and cultivated for the Dutch textiles industry in 1600–1700s and remains widely used as a natural food dye; it provides the yellow in cheddar cheese and is also used for lipstick and blushes. As it appears in For those who stand at the shoreline, the seed indicates these long histories of colonial power and control, but it could also be re-inscribed with different meanings.

Arawak recounts how in the 1500s, three hundred balls of Urucum paste were traded with the Dutch for 300 cotton hammocks, to describe how regional products were inserted into an international market and to illustrate an economy of seeds. He suggests art is also a means of seeding ideas into different circuits of power, so might the Urucum germinate as another kind of politics? Indigenous art in Brazil is marginalized, Arawak tells us, but for the first time it will be included in the São Paulo Biennial (now postponed until 2021).13 As an expression of indigenous subjectivities according to their own perspectives and cosmologies, might such art entering the global circuits of exhibition production and education offer a means to gather; to consolidate power to counter the colonial state. Might (indigenous) art seed revolution in Brazil?

Such calls to decentralize and redistribute power and for post-national solidarity recalls early net art-actvism, such as the “virtual sit-ins,” organized by the Electronic Disturbance Theatre in support of the Zapatista uprisings in the 1990s. These were effectively “distributed denial of service” (DDoS) actions, in which “netsurfers” around the world simultaneously accessed the websites of organizations regarded as symbols of Mexican neoliberalism, such those of the then Mexican President Enersto Zedillo and the US White House of President Bill Clinton. Protesters would repeatedly reload their browsers, overwhelming the targeted sites with requests and thus crashing the servers that hosted them. These actions gave rise to the first net-art activist tool, the java-based applet FloodNet, and tactics that would be later weaponized by groups such as Anonymous.14 For a more recent example of this kind of activism we could think of Korean K-Pop fans bringing down US police channels with excessive fan-jam and disinformation, in support of the uprisings by movements for Black lives.15

The seed analogy also brings to mind the “Seeds of Marielle,” a movement that arose out of the murder of the queer Black councilor for Rio de Janeiro, Marielle Franco in March 2018, allegedly killed by people connected to Bolsanaro family.16 Arawak tells us he also survived a murder attempt in 2019.

Arawak’s rhetoric make use of historical repetitions and relations that echo through time. He tells us that he has an ancestral connection with Germany that is now being re-activated and I note that our conversations often chart personal narratives that are carried across global movements, informed by colonialism and trade and also friendship and study. “In the 1500s the world was already connected but at a different speed,” Arawak announces, recalling the English poet and explorer Walter Raleigh, “the lover of Queen Elizabeth,” who first brought tobacco to Europe and also Arawak people. “We are not going to stop coming,” he asserts.

[1] https://2020.transmediale.de

[2] https://www.luiza-prado.com/shorelines

[3] Audre Lorde, A Litany for Survival (1978), https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/147275/a-litany-for-survival

[4] Luiza Prado de O. Martins, All Directions at Once (2018, http://alldirectionsatonce.schloss-post.com/

[5] Transmediale: conversationpiece, 2016, https://transmediale.de/content/conversationpiece

[6] Kristoffer Gansing and Inga Luchs (eds), The Eternal Network: The Ends and Becomings of Network Culture, Institute of Network Cultures, Amsterdam, and transmediale e.V., Berlin 2020, https://networkcultures.org/blog/publication/the-eternal-network/

[7] Galeria Jaider Esbell, http://www.jaideresbell.com.br/site/category/noticias/page/5/

[8] Kate Martyr, Brazilian lawyers implore ICC to launch genocide investigation against Bolsonaro, DW, 29 November 2019, https://www.dw.com/en/brazilian-lawyers-implore-icc-to-launch-genocide-investigation-against-bolsonaro/a-51459855

[9] AP/Reuters, Brazil: Illegal loggers kill indigenous man during Amazon attack, DW, 2 November, 2019, https://www.dw.com/en/brazil-illegal-loggers-kill-indigenous-man-during-amazon-attack/a-51094361

[10] Indigenous Blood, Not a Single Drop More, https://en.nenhumagotamais.org/

[11] Coronovirus Brasil, https://covid.saude.gov.br/

[12] Vatican News Faleceu Vovó Bernaldina Macuxi, vítima da Covid-19, 25 June 2020, https://www.vaticannews.va/pt/mundo/news/2020-06/faleceu-vo-bernaldina-macuxi-vitima-da-covid-19.html

[13] 34th Bienal program extends until the end of 2021’, 1 July 2020, http://www.bienal.org.br/post/8088

[14] FloodNet, Electronic Disturbance Theater 1998, Net Art Anthology, https://anthology.rhizome.org/floodnet

[15] Justin McCurry, How US K-pop fans became a political force to be reckoned with, The Guardian, 24 June 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/music/2020/jun/24/how-us-k-pop-fans-became-a-political-force-to-be-reckoned-with-blm-donald-trump

[16] Sérgio Ramalho, Who Killed Marielle Franco? An Ex-Rio de Janeiro Cop With Ties to Organized Crime, Say Six Witnesses in Police Report, The Intercept, 18 January 2019, https://theintercept.com/2019/01/17/marielle-franco-brazil-assassination-suspect/