Issue 4/2020 - Contemporary Artist Writing

Wolfgang Paalen – The Writing Surrealist

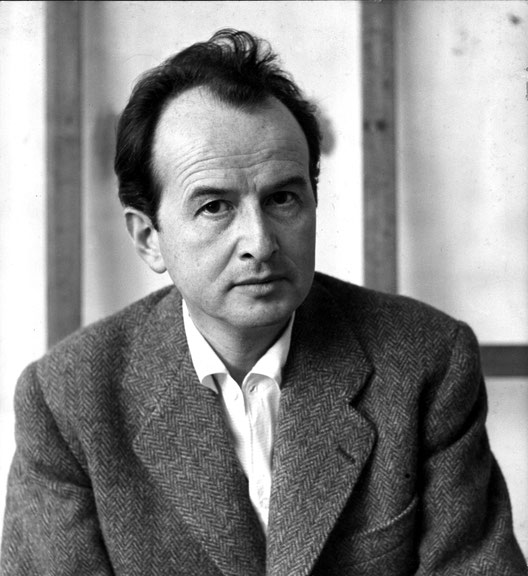

Interview with the Art Historian Andreas Neufert

Wolfgang Paalen was the only proponent of what is dubbed Viennese Modernism in the circle of Surrealists in Paris and experts in particular view him as a major influence on mid-20th century art. After first being part of the Paris-based group Abstraction-Création, in 1935 he joined the circle of Surrealists around André Breton and created an extensive complex of works in the period up to 1940 that addressed his childhood experiences of perception, hallucination, lucid dreaming, visions of ghosts, and epiphanies. He became known for his Fumages, painted with candle smoke, his Surrealist assemblages, and the International Surrealist Exhibition of 1938, for which he created the first immersive modern art environment, working together with Marcel Duchamp. He also became known in America in the 1940s as the founder and editor of the counter-Surrealist art magazine DYN, which enjoyed broad-based reception among the emerging avant-garde in New York, especially during his exile in Mexico. He was regarded there as emblematic of the artist writing and reflecting, especially in the early phase of Abstract Expressionism.

Springerin: Last year, in early October 2019, the exhibition “Wolfgang Paalen. An Austrian Surrealist in Paris and Mexico”, which you curated with Franz Smola, opened at the Lower Belvedere. Towards the end of the show, in the last room before the exhibition film, you presented a small selection of original manuscripts to shed light on “Paalen as a man of letters”. As a painter and a writer on art theory, he is now sufficiently well known, thanks in part to your activities as a curator, journalist and director of the Wolfgang Paalen Society. His short stories, plays, drafts of novels, aphorisms and poems, on the other hand, remain largely unknown. How are these prose texts to be classified in the context of the idea of the “artist writer” reflecting above all on art theory and anthropology?

Andreas Neufert: First of all, I wouldn’t necessarily say he’s sufficiently well-known. It took me 30 years to penetrate the mystery of Paalen, who is perhaps the last great modernist of the first half of the 20th century, and to shed light on all facets of his life and work. It is simply not possible to convey this to the general public with just a couple of museum exhibitions, a biography, and a few catalogues that are, moreover, primarily addressed to the German-speaking world. However, as a visual artist Paalen is now certainly more accessible to us than he was 30 years ago, also in the context of his texts. His prose work can certainly be described as a small gem still to be unearthed within this panorama: a small but wonderful treasure trove of at least seven short stories, three plays, and numerous poems and aphorisms still languishing in the archives. I was recently honoured to write a foreword for the [Spanish/German]bilingual first edition of one of the longer short stories published in Mexico El axolote / Der Axolotl (Edición La Jaule Abierta, Mexico 2019 (ed.) Roger Bartra). Especially in the last years before his suicide in September 1959, in the semi-stable phases between mania and depression, in a secluded hacienda in Yucatàn (fig. 2) to which he temporarily retreated, Paalen, having resolved to die, spent a great deal of time looking back on his life in writing. Without roots in an old, familiar context, without a specific origin, as he put it, he found he had grown too far-sighted as a painter and lamented a failure to come close to individual experience, the lack of a certain intimacy, a certain instinctive familiarity with the imponderables of the ambience, by which he meant nothing other than home. Der Axolotl, in particular, is inspired by such yearnings for a sense of home that suddenly emerge out of nowhere. It is, in a sense, a prose answer to the question – posed directly from the mirrors of his paintings – of what he himself actually still represents, a question that he always wanted to ask the viewer explicitly in his images (fig. 3). And the answer takes the form of a hermetic anamnesis. In this context, his narrative tone in part echoes Stefan Zweig and in part, in its poetic hermeticism, evokes the magical realism of writers such as Juan José Arreola or Juan Rulfo, sometimes disrupted by a highly wayward irony and essayistic interjections. The protagonist is Ignacio, a doctor with an “unfinished profile” who behaves like a collector, seeking to supplement lost parts of his soul with “found” figures, characters and objects. In a second-hand shop, Ignacio comes across relics of the Austrian Emperor Maximilian and begins an imaginary journey through the monarchical world until his execution by Mexican soldiers. And since the soldiers initially missed and hit the Emperor’s eyes, they replaced them before embalming him with the obsidian eyes of a Guadalupe statue, Mexico’s true mother goddess, from the nearby church, not realising that this volcanic stone – “the blackest thing in the world” – carried immense symbolic power. Maximilian’s corpse was returned home to Austria with the eyes of the Mexican primordial goddess, and only the old second-hand dealer in Yucatàn knew what was going on. Paalen weaves his own reminiscences into this story like the will-o’-the-wisp, distributing them as coded messages of his state of mind to his friends, his only readership. Ignacio spends the night in a hacienda, having been summoned to visit its old, ailing owner, Don Beltrán, and by morning the dilapidated mansion has been transformed into a magical cabinet, with two strangely similar female portraits and a mirror reflecting them. Through the narrative strand and dialogue sections in the fifty-page text, Paalen sets out in search of the images of his childhood. It is a highly peculiar dialogue between two parts of the soul in the style of a swan song, as if a grave were being dug for all that remains myriad, multi-perspectival, still aware that the Self and the Other are merely artificially separated categories. In the hacienda, which is called Las Almas (The Souls), he encounters his possible and real souls. The two girls in the portraits are orphaned twin sisters and the deceased wives of Don Beltrán and his brother Fidelio. However, they quickly mutate in the imagination of the biographically knowledgeable reader – the story is, after all, dedicated to the Austrian painter Marie-Louise von Motesiczky, Paalen’s long-standing intimate friend. The reader realises that the souls of Wolfgang and his brother Rainer may be mirrored here too, the marriage to the twins also constituting an awakening of their own twin femininity and the clairvoyance that once connected the brothers in such an outlandish vein. The family’s disintegration begins when Beltrán falls in love with his brother’s wife and the latter, despairing, ends up trying to kill himself with a pistol in his cabinet. The abandoned house in Yucatàn seems haunted by the library scene in Sagan, Paalen’s parents’ castle, where his brother suffered an almost fatal (and self-inflicted) injury with a bullet in 1932 in an incident Wolfgang witnessed. However the elderly mother organises matters, directs the course of events and causes confusion, sending Beltrán to Europe with his new mistress and saving his brother from suicide by telling him that Beltrán had in fact travelled with his own wife, merely believing that he had left with his brother’s wife. However, years later, now on her deathbed, she tells him that she had lied to him, that Beltrán had in fact travelled with his brother’s wife, although she, now also on her deathbed, desperately denies this before she dies. What is love but a hopeful fantasy, a masked ball of the mind? Beltrán is so confused when he returns to Las Almas because he no longer knows whether the woman who remained alone in the hacienda is his lover or his wife, with the result that she too wants to die and throws herself out of the window. The female souls are not believed and thus they take their secret to the grave. Ignacio receives a parting gift from Beltrán, a small double figurine made of raven-black obsidian. The two stocky, very schematic figures, back to back, are so rigorously stylised that only closer inspection reveals a female figure concealed behind the double being. At this point Beltrán recounts the ancient myth of the water god Axolotl (Nahuatl-Aztec, from atl, water, and xolotl, god), who takes the form of a Mexican aquatic salamander. It becomes sexually mature without changing its external larval form or undergoing the kind of metamorphosis otherwise common in amphibians. In Aztec mythology, it thus became a twin creature swathed in mystery, a symbol of the twin-like substance of primordial deities. In an essayistic style, with finely structured subordinate clauses, Paalen builds up to the profound notion that, through beings like the axolotl, the universe points to an even more profound law through the correspondence between two singular beings, although in all other respects the universe’s primordial substance is condensed into the unique, the individual. He extends this insight into the realm of human fate, in which parallel strands of experience, sometimes seeming incompatible with our thinking, suddenly come face to face.1 Paalen seems keen to leave what amounts to a testament for posterity, encoded in enigmatic images, conveying what he saw as the most powerful force driving his art: the axolotl denotes the grandiose hope of correspondence and reflecting that is the sole aim of art.

S.: This magical-hermetic reflection that Paalen’s late prose casts back on his life and understanding of his work is contrasted with the incredible diversity of literature this well-read author may, through the prism of this all-pervading motto of correspondence, have allowed to flow into his own pictorial work, which is shaped by the crises that arose mid-century. What can that mean to us today, especially in times of particular crisis?

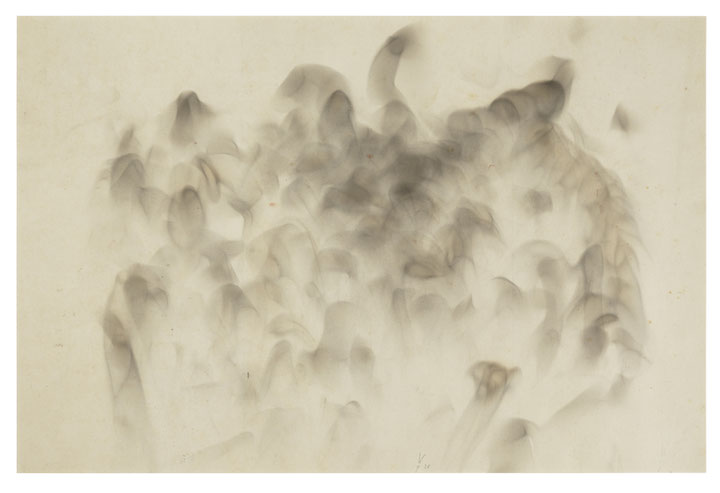

A.N.: Perhaps today the need for reflective writing also stems once again from being obliged to rely much more on oneself, the intimate studio situation, the time that artists can suddenly spend with the context of their own creative output. The Surrealists, after all, had an extremely communicative life as a group in Paris, suddenly followed by the solitude of exile, which in Paalen’s case was filled highly productively through his reflections. The theme of correspondence in Surrealism is taken up with the search for connections between various levels of consciousness. And the corresponding cognitive processes in non-conscious or semi-conscious states, dreams, half-dreams, lucid dreaming, are now once again scrutinised through the prism of theory and reoriented, above all by Paalen. Through quite idiosyncratic views of the era’s reading of these issues, above all Sigmund Freud, Paalen recognised very early on that the only essential difference between waking and dreaming is actually the presence or absence of external reality. In other words, the activity of thought and perception is maintained in sleep in a very similar, if not identical, manner to that of perception with our eyes wide open. That led him to consider what really happens when the ceaseless creation of images and thoughts in dreams encounters external data from the objective world, i.e. when we create an object through our imagination before our mind’s eye that still predominates over the external object when we awake, without being already conditioned by it to something already known. The Surrealists firmly believed that the artist and poet would be able to paint truer pictures, create sculptures, or write poetry by operating free of an imagination forced to comply with the rationale of external vision. This was always too dream-laden for Paalen; within this canon he constantly engaged with the transitional realm, in other words, with a consciousness that, while still latently dreaming, is already looking with eyes wide-open and is thus, in a certain sense, closer to that of the inspired visionary, daydreaming poet. That, of course, had direct consequences for his approach to his pictorial compositions, as well as determining the gaze and preferences he brought to the avant-garde arena from around 1930, entering this context with the perspective of a late-modern Cubist, rather than, for instance, as a Surrealist. As well as being shocked by the gaze-driven rhythm of paintings by Picasso or Braque, Paalen discovered something in them that had simply been overlooked. Cubism was an unfinished symphony that someone had to continue composing. This assessment becomes apparent in the letters in which he recounts first encountering works by Picasso and Braque from their Cubist phase and above all in his essay On the Meaning of Cubism Today, published in his magazine DYN in 1944 and addressed primarily to young American artists. As an introductory quote, it includes the following sentence by Braque: “In the early days of Cubism, we – Picasso and I – were preoccupied with what we felt was the search for the anonymous personality”. This is the key for Paalen, which he very quickly relates to the totem, the invisible divine of the ancestors, with whom it is vital to enter into conversation. (Text excerpt 2) Religious feeling when confronted with large, anonymous images of God is transformed from a fixed identity at a distance, through the stylistic and compositional novelty of Cubism – i.e. the connection between the space that is oriented towards the viewer and the temporality of the observing gaze – into a second I capable of dialogue, which leads to a completely new spatial situation for painting. The viewer’s inner personality, reflected in the anonymous face, becomes the subject-matter of the painting, thus capturing at the same time something of the way in which images of gods emerge, as it were, from the fog of unconscious fears and unexplained desires, while also revealing how the hidden self-idolatry in religions functions. That is a very new, very exciting, disturbing situation straight out of ancient theatre: suddenly a masked person appears in the midst of an unmasked group of people. Everything falls silent. The masked person steps out, strides up to you, stands in front of you, silently questioning like a sphinx. Very close. And suddenly you realise that you are the sphinx. I don’t think there is a more exciting situation for an artist to bring into a painting or sculpture. This anonymous personality figures in Paalen’s paintings from the very beginning, appearing again and again in various forms, in different visual languages, in new constellations. Mostly as a mask, as single eyes, as a questioning look, as a faceless face. Like a man possessed, Paalen pursues this questioning non-face, the archetype of all images, while leads him very quickly to the Surrealists, via a brief post-Cubist phase. For him, Surrealism, of course, meant first and foremost enormous compositional freedom, opening up channels into the unconscious, favouring lyrical narrative structures and highlighting childhood as the source of all poetry. In the fumage method (fig. 4, 4a), with its ephemeral traces of soot wafted from a candle onto canvas and paper, he approaches his childlike epiphanies, which he described to André Breton as “my hallucinatory certainties”. This was his theme, which he would tackle throughout a lifetime of painting. In its unadulterated form, fumage is pure poetry; it describes, in a sense, how thought is formed from the nebulous cloud within the mind that precedes a clear thought. To describe it, he came up with the metaphor of the wish that knocks from within, unrecognised, on the door of consciousness and wants to make itself heard. And texts, such as the essay Surprise and Inspiration, published in DYN in 1942, explain these connections without any reference to his work (text excerpt 3). In reality, however, they reflect and to some extent explain what was happening on his canvases in the years before. His oeuvre is thus the basis of an accompanying narrative and theoretical reflection, which ultimately led him to found his own art magazine in Mexico as there was a lack of other publication opportunities.

S.: So literary and academic sources flow into the process of image-creation, with these images in turn then stimulating reflective writing. Despite all efforts to make his texts independent, they can never be completely separated from his pictorial oeuvre.

AN.: Perhaps a brief look at Paalen’s first fumage-based oil painting, Pays interdit (Forbidden Land) (Fig. 5), will help to shed more light on this connection. It is a very enigmatic, apocalyptic painting from the time of his first separation from his first wife, the poet Alice Rahon. The planets crash like celestial meteors into the abyss of the Earth, the maw; a Cycladic idol figure looks down from above and a kind of Venus planet floats like a fortune-teller’s glass ball inside the Earth, enclosing female bodily forms. Despite the symbolic allusions, the impression of a highly personal landscape of the soul prevails and can hardly be resolved by means of codified literary sources, in contrast perhaps to contemporaneous paintings by other Surrealist artists. Particularly when it comes to the development of the large fumages from 1938-39, Paalen’s early preoccupation with the Dionysian side of Greek tragedy is generally important here, by which I mean that the event-oriented character of the surprising, frightening and anticipatory appears here as a theme per se, i.e. without a narrative context. It is always in the foreground of the pictorial work as well, which springs essentially from the classical literature of Antiquity; as a critical Surrealist, he attempts to move it back into the centre of art via the fumage works: the religious experience of epiphany, the sudden appearance of the gods, seen in modernity, of course, as the secular appearance of figures from the disinhibited nocturnal side of consciousness. Compared to his contemporaries’ works, these images, in addition to their mysterious abysses and ruptures within reality, display a new kind of shock that focuses entirely on hallucination and the accompanying mood: the shudder that runs through you when normal reality is degraded by beings that suddenly appear, turning it into a veil full of inner fractures and imponderables.

S.: So it would seem that there are no specific sources, but instead deliberate avoidance of the kind of illustrative tendencies that prevail, for example, in Dali’s work. A clear commitment to a direct emotional response in the viewer. How is this tendency towards hallucinatory shock manifested in Paalen’s Surrealist objects?

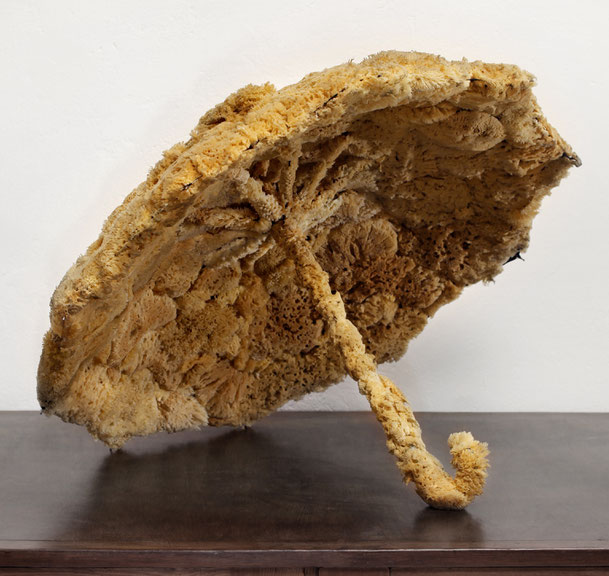

AN.: Nuage articulé (Articulated Cloud) (fig. 6), an umbrella covered with natural sponges, has become particularly well-known; it took up a central position in the Belvedere exhibition and will now be displayed as a permanent loan to the Upper Belvedere from 2021. In fact, when this object was first presented at the legendary Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme in Paris in 1939, it hung menacingly from the ceiling by a thread. Here again, various levels interact, including of course the allusion to the famous umbrella of Isidore Ducasse, alias Lautréamont, who described the beauty of a young man in The Songs of Maldoror through combinations devoid of correspondences: “He is as beautiful as the chance meeting, on a dissecting table, of a sewing machine and an umbrella”. Paalen's umbrella counters this by a dazzling reintroduction of the subliminal correspondence; occupation of space as a symbol of masculinity, protection from natural phenomena, the phallic, sword-like dimension subtly reversed by means of an emphatically feminine object, the sponge with its erotic connotations, the open, receptive umbrella as a flower or vulva. However, there were also political correspondences: in 1939 Nuage articulé was published in the London Bulletin with a commentary alluding to British Prime Minister Chamberlain’s umbrella when the appeasement policy applied for the last time at the Munich Conference proved to have failed. Goebbels wrote in his diary at the time, with his characteristic abysmal cynicism, “Chamberlain may know something about umbrellas, but he knows nothing about politics”. Despite all these more period-specific interpretive associations, the umbrella has retained its direct hallucinatory quality to this day. This is also true for Paalen’s best-known object, apart from the umbrella, Le genie de l'espèce (The Genius of the Species) (Fig. 7), which is made of small animal bones in a duelling pistol box from 1938. There is a very explicit reference here to a short essay from 1942 that also appeared in the first DYN issue, Proposals for An Objective Moralism, which reflects on political misuse of the Machiavellian assertion that “the end justifies the means”. (Text excerpt 4) Le genie de l'espèce discreetly alludes, almost presciently to this, making vividly apparent that ends and means can never be conceptualised separately, that the gun as a means per se always already contains death as an end. I posted this on Facebook once when an American shooting blindly into a crowd in the US once again stirred up the gun debate. I asserted that when faced with this object you understand immediately that the gun lobby’s main argument, namely that if everyone had a gun there would be no more deaths, is entirely off the mark even simply as a line of argument. And here, too, literature has played its own discreet part; think of Anton Chekhov’s dictum that “if there is a gun on the wall in the first act, it will be fired in the last act”. The possibility inherent in a means is at some point realised as if of its own accord.

S.: In Paalen’s case, an impression arises that a great deal of thought and reflection had accumulated in the last years in Paris before his exile and was then suddenly really flung out, in a way that was unexpected for everyone, almost exploding out of him.

AN.: The entirely new situation in which he found himself in exile certainly fostered the synthesis of ideas that had already engaged his attention in Paris. That is shown very nicely in the aphorisms he noted down during his expedition through British Columbia and Alaska in 1939 and his first months in Mexico. At one point he writes about curved thinking analogous to Einstein’s space-time curvature (text example 5). The non-linear play of thoughts is a basic building block in his texts and paintings; on all fronts he immediately removes the perspective adopted in commonplace modes of thinking, almost like an a priori meditation. Inspired by the epistemological implications of the theory of relativity, he relentlessly strikes blows at sublime thought patterns in more recent Western philosophy; above all, he repeatedly takes aim at Hegel and Marx, setting their views in contrast to a philosophy of contingency beginning to take shape and profiting with great self-confidence from the emerging debate on quantum physics – a subject hardly any artists were addressing at the time. These areas of thought also gave rise to the title of the art magazine, in English and French, with which Paalen stirred up the scattered art world during the war years: DYN, derived from the ancient Greek term κατὰ τὸ δυνατόν, that which exists according to possibility. The main focus in DYN, besides the importance of Cubism and quantum mechanics, was his ethnological explorations of pre-Columbian art, particularly Mayan and Olmec art, especially the totemic art of British Columbia whose matrilineal culture and concept of space in sculpture and painting particularly interested him. (Fig. 8)With DYN, which he published from 1942 to 1944 from his Mexican exile, Paalen created one of the most fascinating art periodicals of the 20th century. However, what is particularly striking in the context we are concerned with here are the many sometimes clairvoyant, subterranean correspondences that emerge, such as Paalen’s description in his essay on Cubism of how our eyes move when looking at a Cubist painting; something of his own paintings of the time is carried over into this analysis and is somewhat anticipated by Pollock’s body movements in the first Drippings. The description of the totemic rites and dances in Totem Art as “frenetic action” bears a similar connection to Pollock in particular but also to Martha Graham, both of whom were demonstrably inspired by this text. There are astonishing correspondences even in secondary texts, mostly reviews that Paalen himself wrote for DYN, in some cases under a pseudonym, such as the way in which he describes André Breton’s major poem Fata Morgana from 1943 in DYN 4-5 more or less from the experience of his own painting. This intercontextuality, the subliminal interweaving of his writing with his pictorial oeuvre, becomes clearer the longer one studies Paalen’s texts and his paintings.

Excerpt 1: “and who knows, does not want, in a universe in which even the single variation, the original substance, however small, nevertheless condenses again and again into something unique, however transient – does not the rare identity of two singular things, even if it is not ultimately absolute, even if it is only perfect to the naked eye – nevertheless want to direct the foreboding, like a parable, to something distant and corresponding to us? Is there not also a twin-like quality in the parallel lines of fate in the course of which experiences that are sometimes completely irreconcilable in our minds suddenly come face to face?”

Text Excerpt 2: “Never will anything be more moving than intimate conversation with the totem in human twilight, greater than theocratic solarization in Egypt, more fascinating than the orchid sculpture of the Maya, more airborne than oceanic, more bewitching than African, more daring than Greek art that dared to surrender the image of God to the image of humankind, more fervent than the icy fire of Byzantine mosaics, more terrifying than the apocalyptic butterflies of Bosch, more heartrending than the holy women of Grünewald, more tender than certain Impressionist strolls, and once again more monumental and graceful than the spectral statues of Seurat. And the purely Cubist arrangements seem forever, to those who set out into the duration, whose maps are yet to be written, whose depths are yet to be probed: the new space.”2

Text excerpt 3: “Who is it that, in the midst of an apparent calm, suddenly causes the mysterious breeze to arise that seizes that meager vessel of the ego, whether it likes it or not, to hurl it down into the vast ocean of vision? In other words, what are the external and internal stimuli which produce this phenomenon of interruption of conscious conduct – this phenomenon so difficult to grasp, but so alike in its manifestations, that for two thousand years no other name was found for it than that of inspiration?”3

Excerpt 4: “Analogous dictatorial methods produce equal miseries, every gospel ends in a church, and well-meaning lies are as voracious as the others. For the same reason every party spirit leads to oppression. If the temporary coexistence of two moralities – on the one hand, one of means and on the other one of ends, one with exalted principles for internal use and the other cynical and opportunistic, adaptable to external ends – seems theoretically possible, in practical terms the ruling instinct of the strongest is never delayed – as all history shows – to find the best reasons for interchanging application of these two moralities at will”. 4

Text excerpt 5: “Would it not be time to introduce into philosophical thought a concept analogous to non-Euclidean geometry? Philosophical thought has remained entirely in the context of perspective. (...) Each time, thought rises up to a straight line extending from a given A to a hypothetical B. But what if the passage of time in one direction is nothing but an optical illusion? If time were curved (see to what degree this follows from Einstein’s results). Curved time corresponding to curved space. If one were to analyse the mechanism of thought very carefully, one might find a natural deviation of thought in the same causal chain of rigid appearance – this deviation would remain unconscious, only the real aberrations of thought would become visible”.5

Translated by Helen Ferguson

[1] Wolfgang Paalen, Der Axolotl. Mexiko (La Jaula Abierta) 2019, S. 138.

[2]f About the Meaning of Cubism Today, in: DYN 6, Mexiko 1944, S. 4ff. (franz. Actualité du Cubisme, S. 52ff.).

[3] Surprise and Inspiration, in: DYN 2, Mexiko 1942, S. 5ff. (franz. Surprise et Inspiration, S. 36ff.)

[4] Suggestions for an Objective Morality, in: DYN 1, Mexiko 1942, S. 17ff.

[5] La pensée courbe, in: Vermischte Kurzschriften (unveröffentlichtes Tagebuch), Getty Research Center, Los Angeles.