Nothing hurts like the strike of a returning boomerang, pain is amplified by the rage that comes with the realization it was self-inflicted. This is of course again about the antisemitic images including that of an Orthodox Jew as a suit-wearing, cigar-chewing monster. They set off from Europe then travelled across continents and generations and landed back, in an altered form, on Friedrichsplatz, Kassel’s oldest square and the hub of Documenta.

Antisemitism, just like other defected European good, were amongst the gifts of colonialism thus returned. Ade Darmawan of ruangrupa gave more detail in his Bundestag presentation. Antisemitic visual language, had been brought to Indonesia, which today has a population of 275 million with a tiny Jewish minority, by Dutch colonizers and German migrants. Colonial violence, he said, has often entailed pitting non-white people against one another. In the case of Indonesia, Dutch colonial officers encouraged the demonization of Chinese minorities by applying ‘originally European antisemitic ideas and images to portray Chinese in the way Europeans have portrayed Jews’. Art historians have gone on to explain that once they arrived in Indonesia, these stereotypes worked their way into the wider cultural imaginary, mixing with local artforms – in particular, with Javanese shadow puppet theatre, or wayang, which already had its own cast of beak-nosed villains and dancing grotesques. An antisemitic trope was quickly assimilated into their company. Javanese shadow puppets, in turn, influenced the political art of the post-Suharto era, when cartoon monsters from children’s theatre were the perfect vehicle for commentary on three decades of oppression.

Hannah Arendt and Aimé Césaire used the metaphor of the boomerang to explain the relationship between antisemitism and colonialism. European fascism, Nazi totalitarianism and the Holocaust were, as they saw it, the homecoming of the racism and violence that European empires had unleashed across the colonial frontier. The boomerang that hit Documenta had another, secondary trajectory, however: European antisemitism had returned home in the altered guise of an anti-colonial work of art. This was the ‘return of the re- turn’, to use a psychoanalytic hyperbole. No one can blame Jews for being appalled at finding themselves at the point where these two orbits cross, the intersection in the figure 8 they draw.

After they landed in Kassel, these images started mixing with another local context, that of contemporary Germany and its own shadow theatres. Here the defense of Israel is now “raison d'état” and antisemitism is most often identified as opposition to Israel, understood as a problem imported with immigration, especially from Muslim countries.

What followed was an implosion played in slow motion. the banner was covered with a black cloth, a day later completely removed. The first apologies fell short. Apologies for the apologies followed. The director resigned. In an honest gesture, Hito Steyerl, with a long track record of genuine anti-racist and anti-colonial work, pulled out her piece. She couldn’t tolerate the images, but also the way the “simplistic way the whole issue was discussed and dealt with” in the stupefying public debate that followed. I read in disbelief as some in the German media celebrated the “defeat of postcolonialism”, declared the entire exhibition a national embarrassment, and even called for its shutdown. Members of the AfD demanded the cancelation of Documenta altogether in the name of the fights against antisemitism… New friends.

In their condemnation of the banner, mainstream German politician rushed into their safe bunkers, aligning themselves with the Israeli right which sees the shadow of antisemitism behind every critical discussion of Israel.

The discovery of the images worked as a validation of every far-fetched allegation and confirmed institutional prejudices. In the carnival that followed, farce turned into common sense. Any possibility of differentiation was lost. The real antisemitism of the images was a retroactive proof that all allegations were correct, and served as a license to continue a racist smear campaign against artists, and intellectual from Palestine, the Arab world and the global south.

*

The allegations of antisemitism against Documenta did unfortunately not include discussion regarding the institution’s own legacy – its co-founder Werner Haftmann was a Nazi war criminal – or about antisemitic violence and threats against the remnants of the country’s Jewish community, a persistent problem in contemporary Germany.

It also didn’t include the very local context of the state in which it was help. Despite suggestions that extreme right politics is largely confined to the former eastern states, it is the prosperous state of Hessen, which hosts and funds Documenta, that has been a consistent hub for right-wing violence. In 2006, just a few hundred meters from one of Documenta’s venues, the racist murder of Halit Yozgat took place at the presence of the state’s secret service agent, as FA showed in the previous edition of Documenta in 2017.1 The agent said he couldn’t hear the shots, see the body, or smell the gunpowder as he exited the place after the murder.

Such failure of the senses, we claimed together with the “Society of Friends of Halit Yozgat”, was a metaphor for German institutional oblivion to state sponsored racism. And another attack was soon in the making. In 2020, a racist terror attack took place in Hanau.2 A right-wing extremist murdered nine people with migrant background, while sixteen of the members of the police unit tasked with apprehending him, themselves part of extreme-right internet groups, mishandling the attempt to apprehend him so badly that their multiple failure adds up to institutional abandonment. The former minister president of Hessen, Volker Bouffier said that the fact of their politics does not mean they can’t do their work properly. That they didn’t do their job properly, to say the least, is something that Forensis, the local German brunch of FA, which opened office Berlin in 2021 has clearly showed in an exhibition showing at the Frankfurt KV.

Nothing of that. Rather, the discussion solely focused on the real or presumed politics of the Palestinian artists in Documenta. The farce started six months earlier with a January 2022 blog post by a previously unknown and openly Islamophobic organization calling itself "Alliance against Anti-Semitism Kassel." Though the accusations were unfounded, some German newspapers shamefully started amplifying the message.

A particularly strange line of attack pursued by the Alliance was the inclusion of the Palestinian artists and intellectuals Lara Khaldi and Yazan Khalili, who held leadership position at the Ramallah-based Khalil al-Sakakini Cultural Center because, the Alliance alleged, the center’s namesake, Sakakini – a Palestinian poet, politician and educator who died in 1953 – was a Nazi sympathizer. It is ridiculous enough that Germans would regard Nazi history as a reason for the exclusion of later generations, but furthermore, as historian Jens Hanssen showed,3 the allegations rested on oversimplification of his complex character. In the period of anti-colonial struggle against the British Mandate and growing Jewish and Arab nationalism, Sakakini did see an ally in Germany, though he also maintained friendly exchange with Zionist and Jewish intellectuals. During the Nakba, Israeli forces confiscated his books and they ended up, together with others, as “abandoned property” at the Oriental Reading Room in Israel’s National Library, which refuses to return them to his day. Having lectured and exhibited at the al-Sakaniki Center (though not without some controversy), I know it to be one of the most robust and inquisitive venues for critical debate for a new generation of Palestinian scholars and activists, so much so that the Palestinian Authority, which was not spared its critique, is threatening to close it.

*

The other paradox is that d15 must be one of the best Documentas to date. It is energetic, empathetic, and laid back. visitors enjoy the loosely presented works-in-process, scattered tents and other improvised structures showing videos, live performances, an artist dormitory, a common kitchen, an experimental greenhouse garden and several spaces for collective political debate, mostly about the legacies of European colonialism. ruangrupa’s pyramid scheme – invited participants, themselves mainly collectives from the Global South, were encouraged to invite other collectives, which in turn passed the invitation on – make it irreverent open and democratic, a necessary contrast to the rigid museological style of other art events, and a mockery of the art world’s system of gallery sponsorships and commercial fairs.

The banner in question, 8 by 12 meters, is a massive piece of agitprop, a grotesque cartoon-like version of the political murals of artists like Diego Riviera. It refers to the 1965-6 genocidal campaign waged during the Sukarno regime, which murdered hundreds of thousands of real and imaginary members of the Indonesian Communist Party and ethnic Chinese, as well as to the preceding terror regime of Suharto, the military dictator who ruled Indonesia from 1968 for the thirty years following. The painting, collectively drawn by all members, protests the way in which these crimes are still subject to institutional denial, including by Western countries such as the US, Australia, and the UK, that enabled and supported them. Suharto’s dictatorship wouldn’t have lasted for three decades if it hadn’t had the backing – diplomatic, financial, tactical – of Western governments and their intelligence agencies. Recently declassified documents show that the CIA provided the Indonesian army with lists of targets, while the British Foreign Office stoked up anti- communist feeling by distributing fake ‘émigré’ newsletters and seeding stories in radio broadcasts. As meeting transcripts show, Gerald Ford and Henry Kissinger personally sanctioned Suharto’s invasion of East Timor in 1975. More than a hundred thousand people were killed with the help of US arms. For many artist-activists in Indonesia, as elsewhere in the glob- al south, the brutality exercised by authoritarian governments at home is bound up with their enablers abroad. Unlike the domestic perpetrators of violence, who have names and faces, these unknown others operate in the shadows – which makes it all the easier for them to grow crude and monstrous in the imagination.

The scene is a people’s tribunal. At the center, under a panel of citizen judges, is a black-and-white depiction of the mass murders. On the right are the people, villagers and workers. Everything bad is on the left: the accused perpetrators, and their international backers. Foreign intelligence services such as the Australian ASIO, the British MI5, the CIA, and even a figure labelled 007, are depicted as dogs, pigs, skeletons, and rats marching by a pile of skulls.

Suharto’s regime, known as the “New Order” was finally dismantled in 1998 after a popular uprising and bloody street fighting, in which Taring Padi members, then student-protesters, said they participated and lost friends. The group was formed that year. The banner was drawn four years later in 2002 and was exhibited locally and internationally since with little controversy.

Amongst the images of the perpetrators in People’s Justice, was another image that used antisemitic vocabulary – a pig wearing a Star of David and a helmet labelled “Mossad”. Taring Padi said that pigs were not meant as a slur against Jews, but were traditional Javanese symbols of corruption, and that the Mossad was named because it was involved in supporting Suharto. Indeed, the Mossad did play a small part, alongside other secret services, and the pig figure was used elsewhere on the banner and in other works by the collective. But in Germany, where engravings of “the Jewish Sow” still decorate cathedrals, despite campaigns and legal action attempting to have them removed, this figure, coming from outside European context, was not understood as treating Israel as part of an alliance of western states, but as the singling out Jews.

There was thankfully no attempt to explain away the antisemitic image of an orthodox Jew with an SS hat. He was positioned slightly in the background, behind an equally racist depiction of a Black GI, penis in hand, ejaculating. Not a very subtle piece of art.

*

In their first attempt at an apology, the artists wrote that “the banner seeks to expose the complex power relations behind these injustices,” but such antisemitic representations, when they appear, unfortunately too often within anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist circles, point to an inability or unwillingness to understand complex processes. Such encoded representations are a failure of political imagination. Antisemitism emerges as an explanation, when political, economic and social processes seem incomprehensible, too mysterious and intangible to grasp analytically. The figure of the cigar-chewing Jew then stands in as the personification of the alien and immaterial forces that come to destroy traditional societies or communities. It was thus not only the monstrous way in which the orthodox Jew was depicted, but the figure’s placement within the banner, behind the security forces and in opposition to the harmonious and honest society depicted on the right side of the work, that circles the orbit of classic antisemitism.

When the banner was exposed, Documenta’s failure to spot these images was particularly strongly felt amongst a few of us who for the previous six months had stood by the curators and organizers as they were facing attacks based on unwarranted allegations of antisemitism. The whole thing felt very close and personal, my friends, former students, colleagues at Forensic Architecture were amongst the falsely accused. A member of our Berlin office, Forensis, Emily Dische-Becker, was ridiculously referred to Hezbollah sympathizer by a newspaper thinking itself as serios but acting as the last of the tabloids. Our berlin home, the HKW, was incredibly referred to as the “house of shame”, for having given platform to a group of left-wing Jews who bemoaned the way in which the fight against antisemitism has been taken over – hijacked – by the right and even the extreme right.

*

Other accusations against Documenta participants were based on them having signed the open letter together with some 1,500 others criticizing the 2019 BDS (Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions) Resolution of the German Parliament. The counterproductive, antidemocratic and legally teethless resolution committed the state to denying platforms and to withdrawing financial support from individuals and organizations that accepted Palestinian civil society’s call for non-armed protest in the form of boycotting Israeli state institutions. If not unarmed struggle, what does Germany propose Palestinians do to end their domination? The criminalization of BDS in several Western countries follows Israel’s perception of its risk. When the application of the principles of human rights, international law, and non-armed resistance are described as “the third strategic threat”4 – after Iranian and Lebanese missiles – their delegitimization was referred to as a discursive iron dome. The Bundestag’s BDS motion resulted in the exclusion of Palestinian and their supporters from public platforms across Germany. Palestinian journalists have been fired from media outlets such as DW and WDR. Most often German institutions now simply avoid inviting Arab intellectuals and artists as well as others from the global south for fear that somebody might dig something up.

Critical Jewish voices started also experiencing a little of what Palestinian activists have had to endure. A director of one of Germany’s leading arts institutes noted my public support of BDS when postponing an invitation for Forensic Architecture to show work (not on Palestine, but with Herero communities on the German colonial genocide in Namibia), purportedly to prepare to deal with security issues. In a paranoid language echoing the conspiratorial fantasies of old he suggested that “powerful forces are out to get us… massive guns… directed against our well-being and person, and could ultimately cost me my job… We must first arm ourselves against this.” In early June they quietly cancelled the exhibition. Being denied platform in Germany, under the struggle against AS feels quite unbelievable. More so when traditional antisemitism is still tolerated. I couldn’t hardly believe it when, a few years ago, I actually had to refuse one of Germany’s important prizes for architecture, the Schelling Prize, which is not named after the philosopher, but after one Erich Schelling, an architect, early member of the SA, who later designed buildings in areas colonized by the Nazis. The prize was given to another and my refusal hashed.

*

In the month preceding the opening of Documenta, events seem to be piling up one after the other. To try to calm this storm Documenta prepared a series of panel discussions to address the question of antisemitism. In late April, the Central Council of Jews in Germany complained in a letter to the culture ministry that they had not been invited, and that the inclusion of a panel on “anti-Muslim and anti-Palestinian racism” seemed itself to be flirting with antisemitic. A few days later, Documenta cancelled the entire event series. The official representatives of the Jewish community, like that of any threatened minority, have the right to define what they find prejudicious and hurtful, and should have certainly need been part. But if antisemitism is to be defined as one’s relation to Israel, Palestinians must be asked what they understand to be anti-Palestinian racism.

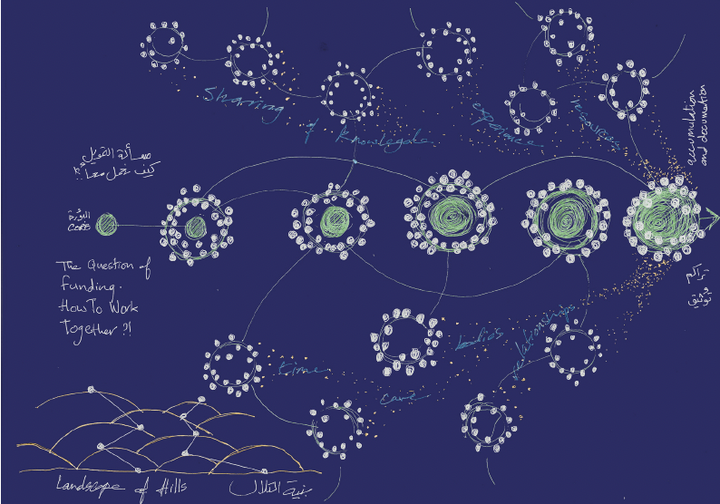

On May 28, in the single most serious incident related to this affair, the rooms where Khalili’s collective, “the Question of Funding”5 was preparing to exhibit were raided by unknown assailants and defaced with cryptic death threats – the number 187, which is sometimes used in the US to refer to murder was graffitied on the wall. The police offered some protection, but the media attacks which may have well set the tone for this death threat have not died down even after it. A few weeks after the opening, “The Question of Funding” cancelled their public program and left Kassel. Khalili, a friend, told me he and his family no longer feel safe there. As he left, Khalili condemned the images on the banner as well as the smear campaign directed against the curators and participating artists. For him, like for the other exhibiting Palestinians living under Israel occupation and apartheid, Jewish Israelis are not abstract figures of hate but a living reality.

*

The curators took responsibility for failing to notice the images, apologized for the hurt caused and promised to learn, but their detractors in German politics and media have not even begun to acknowledge, let alone unlearn, their racist prejudices. They rather use the controversy as an opportunity to give a lesson to artists from the Global South, to Palestinians and to critical Jewish Israelis.

Like the antisemitism that too often exists in anti-imperial circles, Germany’s state-sponsored and openly Islamophobic persecution of cultural producers from the Global South separates the otherwise entangled histories of racism and antisemitism and thus also the struggles against them, placing them at times in opposition with each other.

This makes vulnerable both Palestinians and Jewish people in Germany. They also make it difficult for Jewish Israelis to act in solidarity with the Palestinians. This solidarity, precious, hopeful but fragile, is hard to negotiate even without German help.

Unaware of the discursive constructions that insist on the difference between racism and antisemitism, in the fall of 2019, a German Nazi wearing an action camera tried to break into the single remaining synagogue in Halle and stream videos of himself murdering, in real time, Jews on Yom Kippur. He blamed them for having conspired to arrange the large immigration of Muslims which he perceives as an existential threat to traditional Germany. The worshippers, who noticed the perpetrator arriving on their security camera, managed to bolt the door in time. Failing to get through, the perpetrator killed a passer-by and then ran into a nearby kebab shop often frequented by migrants and murdered a person he believed to be one. In his trial he said that “he didn’t want to kill whites”.

The inability to think together the histories of racism, colonialism, antisemitism and genocide, and to build alliances in the struggles against them may just guaranty we will keep on getting stuck by returning boomerangs.

1 https://forensic-architecture.org/investigation/the-murder-of-halit-yozgat

2 https://forensic-architecture.org/investigation/racist-terror-attack-in-hanau-the-police-operation

3 https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/44043/Who-was-Khalil-al-Sakakini-Diaries-to-Palestine

4 https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/israel-third-strategic-threat/

5 https://documenta-fifteen.de/en/lumbung-members-artists/the-question-of-funding/

A shortened version of this article was published in August by the London Review of Books, August 4, 2022, https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v44/n15/eyal-weizman/in-kassel/; the German translation of the full-length text appeared in Berliner Zeitung, August 27, 2022, https://www.berliner-zeitung.de/kultur-vergnuegen/eyal-weizman-rassismus-und-antisemitismus-werden-kuenstlich-getrennt-li.258319/.