Issue 1/2023 - Zuhören

Politics of Vibration

Music as a Portal to “Topological” Spaces of Experience

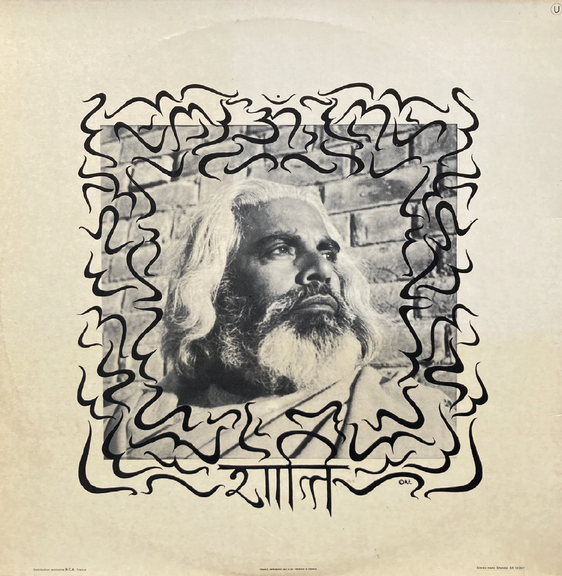

Vibration can be thought of as an artistic medium, a material that can be shaped and worked with. Given that all matter can be understood, according to contemporary physics, as a condensation of sub-atomic vibrations, it would seem that we have little choice but to work and play with vibration. Sound is a kind of vibration. Music is a kind of sound. I propose then that music can be thought of as a particular kind of shaping of vibration – the generation of a vibrational space via sound. In this essay, I will focus on the work of three musicians who produce such vibrational spaces – they might seem to belong to very different worlds: Hindustani raga singer Pandit Pran Nath, Swedish drone composer and mathematician Catherine Christer Hennix, and Houston based hip hop originator of the chopped and screwed sound, DJ Screw. What these musicians have in common is an interest in slowing music – and therefore time – down. Pran Nath’s focus on the alaap section of the raga, Hennix’s drones and Screw’s chopped and screwed mixtapes are all concerned with slowing time down and what happens when you do this, something psychotropic, something in which a new kind of space – vibrational space – opens up to perception. That space is not there only for slow music – but slowing things down can help us attune ourselves to its existence. I do not emphasize “listening” here – the shift to thinking about music and sound as vibration, and in spatial terms, involves rethinking the “thick event of music” outside of subject/object frameworks that are the problematic legacy of the western philosophical tradition, in the direction of networks and constellated events.

When you enter vibrational space, you also start to exit the dominant time regime – which is where, perhaps surprisingly, the politics of vibration comes in. Following Isabelle Stengers, I use the word “cosmopolitics” to describe the kinds of political disputes that ensue concerning the ontology of music. And following Catherine Christer Hennix, I consider what kinds of music, sound and vibration are permissible in a society? In other words, what music is allowed to be. Such questions intersect contemporary interest in “decolonizing music” since it is indeed a mostly European colonial model of music, perhaps warped and stretched via global postindustrial capitalism, which still prevails today. But beyond that prevailing model, I consider how music scenes locate a sense of musical value and try to clarify and amplify this sense. If you are exposed to the richness of vibrational space via music, your sense of ontology changes – vibrational space gathers scenes, musical scenes around it, the way a flower gathers bees in the summertime.

In terms of a slowed down sound, it’s worth listening to Pandit Pran Nath’s teacher/guru, master of the Kirana gharana, and one of the most illustrious figures in the history of Indian classical music: Abdul Waheed Khan. Waheed Khan was a reclusive man and not many recordings by him exist. Singer Salamat Ali Khan said of him that “he would begin to improvise in Lahore, and you could travel to Delhi and back, and he would still be improvising.” According to master sarod-player Ali Akbar Khan, when most singers went to the radio station, they would sing their ragas and go home. Abdul Wahid Khan would continue for another 20 hours or so. Once, a disciple asked Abdul Wahid Khan why he only sang two ragas, Todi, a morning raga, and Darbari, an evening raga. Abdul Wahid Khan responded that he would have dropped the latter, if the morning would last forever.

You can hear Wahid Khan’s style if you listen to maybe his most famous student Hirabai Barodekar – and you can hear it when you listen to Pandit Pran Nath. For Pandit Pran Nath music’s core was a matter of practice, of taking care of the voice and of attunement to the raga’s unfolding in the contingency and necessity of the moment. For anyone thinking about “sound art”, Pran Nath’s perspective on sound is a rich and complex rejoinder to hegemonic western ideas about sound – an articulation of “otherwise worlds” to be found in the vast and complex world of South Asian musical tradition – but also an errant and modern trajectory through a post-partition India and Pakistan that was not always sympathetic to the things that Pran Nath valued.

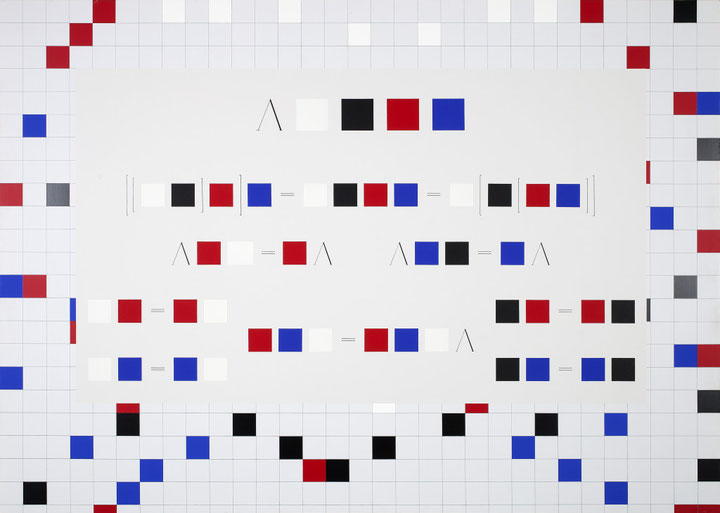

Swedish composer and mathematician Catherine Christer Hennix was instructed by Pran Nath to continue her research into the mathematical and other possibilities of vibrational space, as her musical contribution. Her most famous recording, The Electric Harpsichord, made in 1976 at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm during her ten-day festival of sounds, is apparently built around the scale for Raga Multani – but it exists in a very different sound world to traditional Indian music. In my years of conversations with Hennix, I gradually came to understand an entirely new kind of philosophy of music that she was setting out. Hennix proposes that we think of music in relation to certain target states: music can aspire to states of elevation, spiritual transformation that are both individual and collective. While many musicians and listeners might agree with that, Hennix has pursued the question of whether there are particular kinds of logic, practice or musical procedure that can generate these states - in fact that for her is a meaningful definition of composition, a “Deontic Miracle” to use the name of one of her bands from the 1970s ... “deontic” ... a set of logical rules governing an ethics of permission and/or prohibition ... “miracle” ... something that happens despite its impossibility ... “deontic miracle” ... a set of logical rules that generate a miracle.

While Hennix insists that it is only perhaps a very limited number of musics that actually pursue these ideas with complete rigor – my own feeling is that all music worth the name pursues this kind of “deontic miracle” to varying degrees. And those events or entities that work towards this miracle via the shaping of vibration are in fact what we call “music”. It doesn’t necessarily require knowledge of advanced mathematics – it requires the ability to improvise a sonic or vibrational pattern out of the social, political and environmental possibilities of the moment in such a way that it moves people. The idea that there are mathematical aspects to such improvisation is an intriguing one and it’s instructive to compare Hennix’s ideas with those of Guerino Mazzola, whose epic book The Topos of Music presents an expansive and nuanced take on the mathematical modeling of music via the tools of algebraic geometry and more developed by the French mathematician Alexandre Grothendieck and his colleagues in the mid 20th century. And through thinking about Julian Henriques in his book Sonic Bodies, in which he explores the various vibrational bandwidths involved in a successful Jamaican sound system session: basically the material (the components of the actual production of the actual sounds in a space, from speakers to acoustics to the physics of sound), corporeal (the existential movements and acts of those who generate the sounds, DJs, MCs, musicians, dancers and audiences etc.) and sociocultural (the broader dissemination of a culture of sound such as Reggae, which conditions the above factors in specific ways) bandwidths . From this I develop the mathematical/philosophical idea of a topos as a model for vibrational space – a space in which transformations can happen.

This word “topos” comes from mathematics, where it formally describes the possibility of an abstraction of space that is capacious enough to hold different mathematical models and their possible translations. But it also has a philosophical heritage, going back for example to the Kyoto school philosopher Nishida Kitaro’s use of the word to articulate an open and abstract notion of place. Hennix in particular is fascinated by the idea of a topos. And for her a topos is a space in which transformations from one state, one structure, one framework to another happen, and in which the framework which dissolves into a different framework nonetheless maintains a structural equivalence with the original framework. It literally is both the music and the vibration and the acoustic space and the feeling associated with listening to the sound, all of those things are stacked on each other and in a sense, they are each other and yet a transformation actually happens such that one moves from one structure to the next to the next. And this is what we might call a vibrational space. And one can make the argument that in fact all music consists in the construction of a vibrational space and it doesn’t really matter what it is, whether it’s a ring tone on your cell phone, whether it’s a classical opera, whether it’s drone, whatever. In some sense, your experience of listening to that music is the articulation of a vibrational space. While in mathematics, the idea of a Topos usually suggests a kind of lateral movement in which a multiplicity of possible models and their translations can be thought, Hennix takes the audacious step of proposing a vertical model in which a stacking of spatial models moves towards a state of ‘ekstasis’ associated with an undivided whole, or One. A spiritual mathematics and music then.

In a practical way what slowing things down seems to do is it makes one aware of this musical topos – generally when music is playing and there’s a lot of change going on and it’s maybe happening at a fairly rapid tempo, you don’t phenomenologically experience the spatial aspect of the music. Nonetheless it’s actually there. If I play one of Hennix’s drones to a group of people, they listen for a minute or two, then I tell them to move their heads around and as they move their heads around, they actually experience parts of the wave space in a different way. They actually can hear the spatialization of the sound and they are literally experiencing the vibrational space. That space is there whenever you listen to music but it gets so complicated in music that changes a lot that you actually have no real way of experiencing it phenomenologically.

I mean the phenomenological experience of it is actually called “listening to music”, but the vibrational aspect of it you don’t hear. So there’s something about slowing things down, which allows one to focus more on what is happening structurally. And arguably it provides a path into the ontological aspect of music, which is there not only in slow music, but which one usually takes for granted. La Monte Young said that tuning is a function of time – that music involves a tactics of attention and that you need time in order to actually experienced the structural properties of music. Conversely, when you are actually attuned, time disappears and you're immersed in a vibrational space where, to use Hennix’s still radical formula, “Being = Space x Action”. Time is replaced by action on/in a space. While the objections to the statement via modern physics are clear – the intuition contained therein will also be a familiar one to anyone who has found themselves deeply immersed in music.

Juxtaposing Houston based DJ Screw with Pandit Pran Nath and Catherine Christer Hennix might seem like a strange thing to do, but in terms of a slowed down sound, Screw’s music is a radical experiment with time and vibration, and a very underappreciated one, thus also one with its own politics. Screw was a hip hop DJ, and used the variable speed controller on his turntables and cassette recorder to slow the music he played down. Screw created vibrational spaces ... they appear like a miracle when he slows things down. It might seem like for Screw, whose almost entire oeuvre consists of a series of 300 plus mixtapes, music was “nothing but the recordings”, yet the gatherings of MCs nightly in the “wood room” of his house in south side Houston in the 1990s also generated a powerful vibrational space that was then transmitted to the massed car stereos of Texas, slowing down time under the most hostile and racialized conditions. In terms of long form slowed music, Screw’s most famous track the 37-minute collective freestyle often just known as “June 27th” on the mixtape Screw made for Demo Sherman on his birthday in 1996 has a powerful sense of social space as vibrational space. These are all tracks about time, about time that gets suspended, stretched, or compressed, as Fred Moten says in his essay “Black Topological Existenc”, into a “topological existence” based on “a mechanics of distress”. Note the resonance here between Moten’s use of topology and Hennix’s formula “Being = Space x Action”, which is basically a topological statement (topology as the cataloguing of the possible variations of a shape or space that nonetheless maintain structural invariants). Those who want to know more should read Lance Scott Walker’s excellent new biography of Screw, or his oral history of Houston hip hop, Houston Rap Tapes.

There’s maybe no easy exit to space the way the white avantgardes tried to imagine it. But that then is the politics of vibration as someone like Sun Ra meant when he said “space is the place”. In fact, I don’t think there’s an easy exit to space for anyone – powerful though variable chains, mental and otherwise, block this for all of us today, and thus we have music in the reified and packaged state that we mostly experience it as. But music can be and often is a project for undoing this. The project is not just that of undoing in the sense of negating existing hegemonic structures but a positive articulation of new vibrational, sonic and musical possibilities. If this suggests to you a kind of static hierarchy of sounds, think instead of what John Coltrane meant when he used the phrase “a love supreme”. Our approach to the One, sonically or otherwise is always contingent, always from a particular place and improvised out of the particular vibrational bandwidths that are permissible in the environment.

I think of this in relation to the Canadian indigenous HipHop crew until recently named A Tribe Called Red, now known as The Halluci Nation. Bear Witness, a member of the crew, reminds us that music sound and vibration emerge from the land, from our own living heartbeats no matter how this is obscured in settler colonial cultures. That is what we mean by cosmopolitics and music as a cosmopolitical practice. We all come to music from different positionalities, and in a sense all human societies improvise the object/event called music out of the environment’s possibilities. This is true of traditional musics – but it is also prospectively true, in the sense that new arrangements, new articulations can and will happen, and our work (and joy) is to amplify and deepen the possibility of those new sounds and the forms of life that gather around them.

Marcus Boon’s The Politics of Vibration. Music as a Cosmopolitical Practice was published by Duke University Press in 2022.