Issue 1/2023 - Zuhören

When Pools Turn Red

Five Artists and Cultural Workers from Iran comment on the Current Situation in their Country

Listening to the written input by five Iranian artists and cultural workers. Four of them, living in Tehran, want to remain anonymous. One of them, Raha Faridi, lives in Berlin since a short while. Compiled, edited and arranged by Hannah Jacobi (Berlin, Germany).

In January 2023, when this text has been compiled and written, a series of executions of four young men sentenced to death for taking part in the protests and charged with "corruption on earth" and “enmity to god” shook the Iranian society and the world. Their names are Mohammad Mehdi Karami, Seyed Mohammad Hosseini, Mohsen Shekari, and Majidreza Rahnavard. Many others have been charged with the same “crimes” and have to fear for their lives. The Iranian regime is spreading fear and terror, trying to wear down the Iranian society and stop the ongoing revolution, as German journalist Gilda Sahebi puts it. However, this seems to be impossible.

The written input of five Iranian artists and art workers does not tell a chronicle of this revolution that was sparked by “Jina” Mahsa Amini’s death on September 16, 2022. They draw a panorama that gives insight into personal situations and traumas, looks at the genesis of this revolution and its power, makes a connection to art and the cultural field, and speaks of hopes and possibilities.

Beginning with personal situations, S., writer and translator, who has a professional interest in film, describes the intense emotions she is experiencing:

I’m not sure if I can put all my feelings regarding the recent situation in Iran into words. I usually try to avoid lyrical language, but this is as precise as I can describe it: I feel an intensive, painful joy that can be experienced only in love or revolution. What has become obvious to me is, that for a long time before these events, I did not really feel alive, and I guess many people here share that feeling. It was like you are living your everyday life with a great depression and maybe a dose of sarcasm. And suddenly you are hit by something extraordinary. I cannot call this feeling hope, just like a cynical person who falls deeply in love would somehow feel that a happy ending can only happen in films and novels. But nonetheless, she is charged with a force much greater than herself that makes living as before impossible. If there is a hint of hope, it is mostly due to this feeling that you might have the chance to be part of something big that makes living worth, to feel that you are really alive, even if only for a short time.

Of course, I also find myself immersed in fears that mostly come in form of what ifs. What if depression dominates us again? What if disappointment among the people gives rise to various forms of fascism? What if the reactionary desire expressed in the slogan “man, nation, development” that is sometimes attached to the revolutionary phrase “woman, life, freedom” prevails? What if hatred stays with us and we cannot get rid of the dictatorship? What if we don’t find a chance to debate and act collectively in solving our problems but instead, like usually, the one who have money and control the media direct the whole movement?

Also J., curator and writer, gives us an insight:

My personal situation is changing every hour depending on the general situation that changes so quickly here. The past months has evolved every one of us in many aspects. I’m experiencing hope, fear, anger, and sorrow all at the same time. Sometimes one of these feelings is stronger than the others but they are all always present. I think we can add hate to this list of feelings when you see all this brutality. I do try to stay away from it, but it is so hard. And after all, despite all these, I am trying to stay hopeful.

I take tranquilizers every day to be able to move on. I have bad headaches. Nightmares every night. I wake up in the middle of the night to check the news. Every unknown contact or the knock on the door is scary and you think it is your turn now. I just meet very close friends from time to time. We sit and talk. There were also a couple of small parties with drinking and dancing, a small chance to get away from all the tension, but soon after you are bombarded with the bad news. I do long walks whenever the air is not too polluted.

Raha, documentary filmmaker and an experimental artist, lives in Berlin since a few months.

I had to leave Iran suddenly a few months ago. One day, fifteen IRGC intelligence officers rushed into my place of residence in Bandar Abbas where I presented a series of screenings of my documentary film Chicheka Lullaby (2018). They entered by force and took all my devices including my hard drives, mobile, lab top… I was interrogated for months. After three court hearings, in which I could only have a lawyer that they had chosen and I was forced to pay a high price for, I was sentenced to one year and ninety days of prison. I was accused of insulting the leader and advertising against the regime. Most of the court case was based on my appearance on social media, my critical contents, what they found on my personal devices, in my chats with friends.

I now realize more than ever how disobeying the unreasonable rules and regulations inside Iran had become a mission in my life. I would be energized by my effort to live my beliefs in a society which hardly tolerates them. I joyously hardly ever wore the hijab, only in the main squares of the cities or in state institutions. I was an absolute independent artist who translated, taught, and crowdfunded sometimes to be able to make films. I never included anyone directly connected to the regime in my work and never appeared in the state medias or festivals. They noticed me when the number of my followers on Instagram increased substantially. I guess it was hard for them to see a female independent artist living her life as she wanted inside the country. Also, the fact that I’m from a Sunni background, which is considered a religious minority in Iran, was mentioned several times during my interrogations and in court.

Raha continues, writing about the revolutionary movement:

This is the strongest uprising Iran has experienced during its time as Islamic Republic. And it is the most important one due to several factors: It is the first women-based uprising in history. This time, people did not protest over gasoline price or election results, but they protested because of a Kurdish woman’s death. It’s the first time that men have appeared strongly in the field asking for women’s rights. It can be called the first secular movement in the history of the Islamic Republic. Not only is it not taking place in the shadow of any religion, but it is criticizing and revolting against the religious leaders and the whole religion-based regime. For the first time the celebrities are realizing that they cannot stay silent and that they must pay a price or else they would completely lose their popularity and might not have a place in the future of Iran, so after many years of holding back, many of them are joining the movement. It is the first time that the majority of Iranians with different gender and political background or interest are trying to practice unity under one slogan “Woman, Life, Freedom” for the shared goal of regime change.

G. is an artist and translator. She goes back in time to make clear that the current revolutionary movement builds on a long history of revolt in Iran, before and also after 1979. She starts with her own family history which shows, how many families in Iran are directly affected by the historical and recent upheavals:

Before talking about the current situation, I think it would be helpful to describe a brief oral history of our past. My father was an engineer but spent most of his life painting. My mother was a teacher. Both were leftists and were arrested in 1981. After prison, my father collapsed mentally and gradually distanced himself from society. Also, my mother got fired. This was the fate of most of their leftist friends who were imprisoned at that time. Some went insane, some committed suicide and some were executed. Of course, some also left Iran. I think that in addition to physical and mental pressures in prison, they thought they had failed their ideals: demanding equality.

I’m saying this to emphasize that our struggle did not start from today. The people of Iran fought for equality since the constitutional revolution in 1905, and again in the revolution of 1978/79, which was against the dictatorship of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Unfortunately, back then, the reactionary forces took over the power and the progressive forces were buried under the ruins of their ideals while the media kept silent. Just take a look at Khavaran cemetery, it is a testimony of these suppressed voices.1

But in the last few years, we have experienced many uprisings. In January 2016, people mostly from small towns and city outskirts came to the streets to protest against high prices. These days coincided with the activity of women known as Girls of Enghelab Street (Revolution Street). In the middle of people’s protest about living conditions, a woman went up on a platform and took off her scarf. It was the most amazing performance I have ever seen. Later, several other women repeated the action. All of them were immediately imprisoned. It may not be tangible for many people abroad but removing the hijab here requires a lot of courage.

In November 2018, people came to the streets peacefully to protest the high price of gasoline and the removal of subsidies. But the internet was cut off and within two weeks the government killed hundreds of people. In Khuzestan2 people revolted again to protest against the lack of water. Farmers, environmental activists, retirees came to the streets many times to change the situation.

Earlier, the teachers' union organized massive demonstrations that initially had union demands, but quickly became political, with teachers chanting against privatization, commoditization of education, and for the right to equal education. Along with it, large labor strikes were held. All of these protests and strikes were suppressed and its prominent activists were sentenced to prison.

Until we reach today: Women sparked the recent uprising, first in Kurdistan,3 and then in the capital. The issue for women is not only to be able to choose what they want to wear, but the matter of equality in the truest sense of the word. Women have been working underground and through social networks for many years. For example, during the pandemic, women started to speak about sexual harassments, and there were many conversations about the patriarchal system particularly in Iran. The women were angry, they didn't want to be victims anymore, they wanted to take back their agency. But soon other layers of the society joined this uprising, against the ruling order. In fact, I can say that "woman" became the code name of all oppressed people. They want everyone, regardless of ethnicity, sexuality, race, or religion, to have a decent “life,” and in my idea, “freedom” is just realized when everyone can live with equal opportunities.

It was and is an important fact in the revolutionary movement that it emanated from province of Kurdistan in Iran and other Kurdish influences cities. Neither do the protests abate in the province of Sistan and Baluchestan, where a large part of the Baloch minority resides. At the same time, cities like Mahabad (province of West-Azerbaijan), and Zahedan (Sistan and Baluchestan) have been and are under enormous pressure from the regime forces, the IRGC.

G. explains:

Since 70% of the wealth is in the hands of 1% of the richest people who mostly live in the capital, unemployment and poverty are much higher in other provinces and cities.4 First, this is caused by the uneven development of capitalism. Further, social freedoms are much less there too. […] Significantly, one can hear the most progressive slogans from Kurdistan. “Jin, Jîyan, Azadî” was first chanted there. The people of Kurdistan speak about equality, women's freedom, socialism, and stand against all reactionary forces and totalitarianism. Baluchestan is one of the provinces that has always been deprived. Many people do not even have birth certificates. The gold mines of Baluchestan are the share of the upper-class who mostly lives in Tehran, as well as the share of the ruling religious bourgeoisie there. The situation in Khuzestan is terrible too. The air is polluted, there is no work, there is no healthy water. And the severity of killings, arrests, and executions has always been higher in provinces other than Tehran.

J. writes:

The issue of “center” and “margin” can be considered as one of the key elements of this movement. Kurds and Baloch, but also people from the Southern parts of Iran and to some extend Turks have been systematically oppressed for a long time. Therefore, all these brave people have been so forward in the last months. But the center is not ready for a change yet because it is still benefiting from the minority’s disadvantage and oppression. On the one side, the masculine society and the patriarchy, the state, and the rich upper classes are threatened by losing their power. On the other side, women, ethnic minorities, queer people, and workers are struggling to gain more power, to be seen and heard. The invisible ones want to become visible and the system obviously does everything to prevent their visibility. This is a very tough game in which Tehran, the capital, has an important role as the main playground. Perhaps one of the things that should change is, that Tehran must not be the center of everything anymore.

Raha points at the high risk that people and activists take in smaller cities or villages:

What I have realized is, that activists and artists are under much more pressure in small cities. They are easier to identify and easier to find. A lot of artists, actors, musicians, and influencers were detained, threatened, and forced to sign a document indicating that they won’t post any anti-regime content on their social media channels.

This was also my experience: Finding me was much easier for them in a city like Bandar Abbas than it would have been in Tehran, where you have the chance to disappear in the crowd. The judges who ruled my case were all from Northern cities. My guess is, that they have this strategy to put officials of other ethnic groups on these cases so that there is no connection and the brutality becomes easier for them.

Not all input givers wanted to write something about their own involvement in the movement. But participation can have different forms, as J. elaborates:

I personally think that “participation” does not necessarily mean one has to go to the streets and confront the regime forces. I also don’t know what your image of the demonstrations is. The things you see on social media and especially on Instagram seem much bigger than the real thing happening in the streets. To be honest, compared to the population in Tehran, not many people take part in the riots. It has many reasons and the most important one is that the system’s reaction is savage and brutal. You can easily get arrested for just being in the street. Therefore, probably going to the streets protesting is not the most sensible thing to do anymore unless in some special cases. Finding ways to help others, educating yourself and trying to stay healthy to overcome this situation is a sort of participation itself.

The most vivid resistance and participation these days are the women who walk in the streets without hijab. I have a lot of admiration for them. I know it is so stressful and sometimes dangerous but looking at them in the streets of the city is like a dream. It is like you have blinked your eyes and you see that “revolution” you have dreamed of for a split of a second. It is beautiful.

H., photographer and publisher, however, is very clear about it:

I was in the street since the first day of the protests. I try to be present and active. The streets belong to everyone, and I can't tolerate it one day longer, that the government wants to forbid us as citizens and as women to simply go out!

The possibilities to do something from afar are limited, but also for Raha, participating in any possible way is important:

I do my best to keep in touch with my family and friends on a daily basis. I follow all the news through media and social media. I can’t say that this much attachment to Iran and what is going on there is serving me well here in Germany. My head and heart are still in Iran, and I have not been able to cope with this new, German society to my best potential. Now that I’m here in Berlin I have more time to digest the whole trauma. I feel that I have literally lost everything I had, my home, my activities, my family, and my community. But “here” feels lonely, cold, and dark, and the constant news of Iran, the killings and the executions make me feel as if my hands are tied up and there’s not much I can do but to feel the pain.

I’m trying my best by raising awareness about what’s going on in Iran, posting and hash tagging on social media, signing petitions and attending the protest in Berlin… Together with some friends, we are writing to diplomats of different countries, asking them to consider IRGC as a terrorist organization and calling on politicians of different countries to expel Iranian ambassadors and recall their own ambassadors from Iran. I personally spend a lot of time discussing the issue with friends inside and outside of Iran, to share experiences and viewpoints.

One of the most pressing issues is the very precarious economic situation in which many people and especially artists and cultural workers currently find themselves. The disastrous economy in Iran and its consequences especially for the working and lower middle classes has fueled the resentment of these parts of the population for years and increased the will to protest.

As G. explains:

First of all, I must say that the living conditions are most difficult for the working classes and the impoverished layers of the middle class. Simultaneously with the suppression of all kinds of organizations, labor councils, and leftist political forces, in my opinion, neoliberal policies adopted by the state, unfair distribution of wealth, corrupt politicians, and the economic sanctions have made the situation intolerable. The queue of unemployed, unstable, and daily wage workers is increasing every day. The streets are full of child laborers, garbage collectors, homeless people, and peddlers. Of course, this class oppression doubles for those who are sexually, ethnically, religiously discriminated.

And further, specifically addressing the situation of artists:

Fact is, that artists in Iran have not had a favorable economic situation for years. Most artists do not make a living through their art. They always do side- and unrelated jobs to provide the cost of their art materials that become more expensive day by day. For example, to be able to afford the material for one of my exhibitions, I worked for a long time in a café. There is almost no funding for research and artistic work. Besides, most of us avoid any kind of work related to the government. The art market is not booming. There are few distinguished artists who can be called successful on the art market and sell their works at unbelievable high prices. The situation of translators and writers is the same. Under such conditions, many of them abandoned the creative work. It seems that today, art is a tool of the upper-class.

Also S. describes the situation as disastrous:

Regarding the artists’ economic situation now, I have to say I don’t know how people are surviving. Honestly, especially those young artists who have to pay rent. I guess their financial resources come from their families, they work in temporary jobs in other fields, cut their budget by moving into very small houses with more roommates or choosing smaller cities to live. We’ll see how far this can go.

H. sheds light on the conditions, artists and cultural workers are forced to work and live in:

If you want to do any [artistic] activity in Iran, you must have a permission from the related ministry. If you want to have an exhibition, print a book, make a movie, have a show, or do any kind of event in the field of art, sport, or the social realm, you must ask for a permission. If you don’t do that, you are going underground. And if you are underground, you are illegal, which means that you can be arrested any time for any reason. But if you want to live freely like a normal person, you have to act in the underground.

As an artist, I've always lived and worked like someone underground, enabling me to do what I wanted. I could never live and work "officially" in my own society, I always had to take certain risks, that became normal for me. One gets used to it and survives in this way, but I know that this is not a normal and healthy way of being! It is not a life everyone wants or can live. I would love to live like a normal citizen in my country.

It has been a heated discussion in Iran and mainly in Tehran if and how the private artistic sector should continue its activities after the movement started. Most galleries haven’t, for several reasons, as S. explains:

As you might know, almost from the beginning of this movement, many galleries have closed their doors and stopped working. I’m not sure, but I guess it was mostly a spontaneous reaction rather than a decision made collectively, as there was no collective announcement. The reasons were obvious: At the very beginning, everybody was shocked by the brutal news of arrests, torture, and killings. Exhibiting works not relating to the situation would have seemed like a bad joke with probably no audience. On the other hand, holding events related to the protests was too risky.

After almost three months, the debate about whether galleries should resume their activities started again, especially after O Gallery officially announced that it opened again. The opening raised many negative reactions and attacks, from splashing red color to the gallery’s building to critical comments on their Instagram page. Opponents saw this act in tune with the government’s desire to pretend everything is normal or they were critical of the activities of galleries in general and the tune of that announcement in particular. Herfeh: Honarmand, an art magazine based in Tehran, took an opinion poll and asked 242 persons in the art field to announce their position regarding the reopening of galleries and published the replies on its website. Most of the respondents emphasized that the question should not be whether galleries open again or not, but how they do it. They criticized that the decisions of closing temporarily were single acts rather than a collective, official announcement that could have had an impact. Of course, such an act would have been impossible in the current landscape of galleries in Tehran: they lack a strong relation with each other and even with the artists they represent, and they do not relate to other parts of society.

For me, the most interesting aspect of people’s reply was their call that, if galleries want to be taken seriously, they should reflect upon their weaknesses and do something about it. Otherwise, nothing much can be achieved from their isolated gesture and there is not much difference between them and other companies. Nobody could have imagined such a clear statement and heated debates among people in art scene four months ago and I hope we don’t stop here and act accordingly.

J. extends the reflections on the role of art at times of revolution:

As for art itself, I think now one can see the close relation among life, politics, and art. Today in Iran, people are interested in graffiti, music, and performances that are created by artists and non-artists. People are contributing what they can to the movement, and they are mostly doing it anonymously. This is probably the reason why the regular programs of commercial galleries are not interesting for people anymore. The image that they want to see and the voice that they want to hear is in the streets and you can find the reflection of this on social media, mostly on Instagram.

I personally think one could see since a long time that the art world and mainly the art market was not able to communicate with a major part of society anymore and there was a big gap between the art world and the “real” world. Not only here, but everywhere, also in Europe. What is happening now in the street of Iran is much ahead of the agenda of the art world.

This is why it was very irritating for most of us to see that someone like Shirin Neshat is being presented in Berlin and elsewhere for the “Woman, Life, Freedom”-movement that is happening inside Iran! I think now, more than anytime else, we understand that the image artists like Neshat (but the list of names is much longer) are introducing the world has not been the whole story of Iranian women and that they have sent a wrong signal to western societies just to make money. I find it very opportunistic of her to dare to appear representing a progressive feminist movement inside Iran that has nothing to do with her or the image of Iranian women she is creating. It is pathetic that the art market wants to exploit everything so soon.

He goes on:

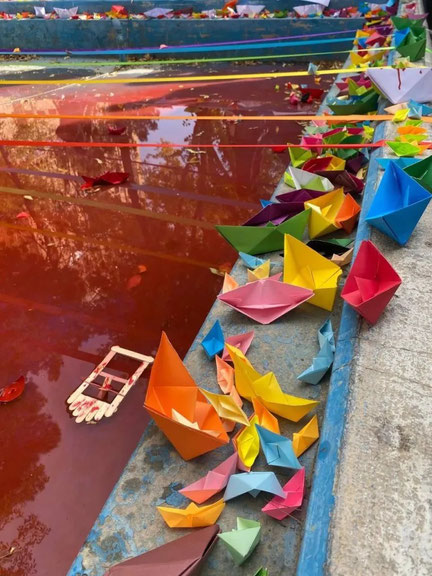

When girls and women wave their headscarves in the streets, when the pools in the parks turn red, when a male beach football player poses like cutting his hair when he scores a goal, when the university students tie down themselves to a pole or a tree to remind us of Khodanour’s image etc., all these examples and many others show and prove how beautifully art is engaged with the current movement in Iran. And I think until further notice this is the art that people want. There is a wide range of things that one can do to create. One can do something very personal like painting in their own studio and solitude or, on the contrary, can do something completely selfless with a group of people or a community without even paying attention to the result. What I mean is that they are all a sort of creating, also in a sense of “art.” Everyone is free to do what they want. It is the most important message of the current movement: Freedom.

G. describes the collective potential that the revolutionary movement has in store for art:

I think all people, if they have the opportunity and time, have a desire to be creative, express themselves through art or see themselves in the mirror of art. In fact, art should come out of the monopoly of the privileged. It should open its way to people's lives. This happened in recent events. Literature spread across the city through slogans written on the walls. Or the spectacular performances performed by nameless people in the streets. I saw wonderful paintings and poems in virtual networks. Rich and magnificent hymns were composed during this period. In the art created by anonymous people, the logic of financial benefit did not prevail. It is as if art and literature underwent some kind of revolution. In other word, it is the art itself that has undergone transformation and affects the society.

What is already becoming clear here is the enormously important role of togetherness, collectivity, and community. G. emphasizes this again based on the possible changes in the gallery scene in Tehran and elsewhere in Iran:

I personally don't know what the gallery strike can exactly achieve in the current situation. We were isolated enough during the pandemic. I think now is the time to welcome any kind of community. Along with the important criticism towards institutions such as the commercial galleries, thinking of creating new forms of community, collectives, cooperatives, and teamwork are amazing and important ideas that are currently being discussed. I hope that eventually at least the countless small galleries and unknown creative artists find new ideas and possibilities.

J., but also others I spoke to or heard from are organizing themselves in small groups among friends to be able to support each other and others: Establishing a fund for artists who find themselves in a precarious financial situation; organizing private classes on art and theory for students who were and are active in the protest – the universities have been places of protest since the beginning and are strikebound; and trying to help those who are even more under pressure by the current situation, such as Afghan migrants in Tehran.

Finally, a few words of hope:

Raha:

This process can be considered an ongoing social revolution, a cultural revision, and an educational path to finally become a free democratic country. I’m not sure how long it might take to reach this goal, but I believe it’s on the way and there is no turning back.

J.:

This is a big transformation that needs time until it finds its way. I’m not sure how it will go forward and I’m not completely optimistic about its success either, but what I can see and feel is that the revolution has happened in many people’s minds and hearts and this will not change or go backwards. We are out of closet!

S. is addressing the people and non-Iranians outside of Iran, in Europe, Austria, and Germany, she’s speaking to us:

I want to say that what we are experiencing here is extraordinary. It’s joyful, painful and scary. In a nutshell, I wish you were all here! Or better to say, please deeply believe that we are in this all together. By that of course I don’t mean to help us through “exporting democracy,” but to begin from your society. Increase people’s sensitivity towards tear gas of European origin, used in Iran despite the sanctions,5 the vast presence of wealthy Iranian people who are close to governments abroad, the Mazut6 we are breathing. But maybe more importantly, about the logic behind all this, and consequently the significance of collective thinking, of finding alternative ways of living, of international solidarity among women, workers, students, etc. This is the only way out of this chaos which we are experiencing today. The irony is that you have more freedom than us in doing so, as we are under a great deal of control, censorship and death threat. But I guess we feel the urgency much more than people in your society who are almost happy about their life for now. I hope art can synchronize us sooner than later!

1 Khavaran cemetery is a piece of land located outside Tehran that is considered one of the biggest graveyards where thousands of political dissidents who were executed in the summer of 1988 are buried. Cf. https://women.ncr-iran.org/2022/09/16/walls-around-khavaran-cemetery/

2 Khuzestan is a province in the very south-west of Iran.

3 Kurdistan is a province in the west of Iran.

4 Abbas Shakri, in: https://www.90eghtesadi.com/Content/Detail/2150437#

5 Through social media, images and educational videos on the origin of tear gas shells fired by regime forces have been shared in recent years and even before 2022, including those produced in the UK but also in other European countries.

6 Mazut is a low-quality heavy fuel oil, used in power plants and similar applications.