Issue 1/2023 - Zuhören

Who is Afraid of Sound?

Listening as Transgression and Questioning of Cultural Visuality

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolf? is an outrageously cruel as well as loving, sad, and utterly bewildering play by Edward Albee that premiered in 1962 at the Billy Rose theatre on Broadway in NYC.1 It performs through a focus on the marriage of Martha and George a clash between reality and illusion; between what we call real, verifiable and true, and what is considered madness, “just” fiction and imagination, with no bearing on the measurably real, but which nevertheless seems to threaten the very frame on which reality is based and reveals it as the delusions of normative expectations. In this case it threatens the institution of marriage, with its binary certainty, that stands as arbiter and symbol of the societal and civic norms of the 1960s, representing a whole host of other norms and truths that determine and limit what is possible.

I start with a reference to this play because, while the standards of marriage as civic norm, the certain binary and theological basis of its symbolism, have, if not entirely been vanquished then at least been expanded, the fear of the illusory, of irreality and fiction, and the allied hope and desire for a stable, certain and perfect reality remains valid if not amplified in the contemporary. We want to be sure that things are real and quantifiable. That you see what I see. For this purpose, the thing we are both looking at needs to be stable, measurable and categorizable; and the language we use to verify a shared view needs to hold this certain measure rather than implode it in a drunken, hysterical and ever wilder mis-en-scène, that threatens not only the credence of the seen, but also of our own subjectivity and our relationship, our social contract: how we live together, what we call things, and what therefore enables our believe in a world made real through objectivity, gained through distance and enabling taxonomic definitions.

The play critiques the ideal of the modern (American) family, identity and society, and by extension the notion of a US-European modernity built on objective ideality, the platonic sense of a mathematical universality in which measurability is more real than the real. Where the meta-frame, which is invariably visual and visualizing, determines the legitimacy of reality. Instead, it celebrates the potential of irreality, fiction, and illusions, as generative of a different social and political imagination: establishing possible worlds that are not trivially possible, as a parallel fiction only, but whose possibility are reality’s pluralities. These threaten the hegemonic frame of normativity the West has built since the enlightenment through its focus on an objective metric, whose truth is assured by distance and verified by repeatability, and that stands as arbiter of an ethical expectation of what ought to be real, the truth, and how we ought to live that truth.

The fear of Virginia Wolf is a fear of irreality becoming real, of certainties collapsing, of paradigm shifts and ontological doubt and of giving in to that doubt to engage in the possible worlds and possible realities and identities that could be real if we would let go of visual references, metric systems and societal expectations and norms. These possible reals are feminist, decolonial, embodied and tacit. They are the realities of the marginal, of that which is not at the center because the metrics of the center exclude its realities, and because they are invisible, positioned as they are in the blind spots of a dominant vision. It is what is not verifiable or legitimized by measurements and canons of (western) knowledge. Thus, it is perceived and excluded as unreliable, as illegible, esoteric, and feminine, standing in for an intersectional other; or simply imagined and even mad. For it to gain the upper hand, even temporarily, is scary. We start to worry about how we will organize things when the (visual) frame of reference has gone. How will we verify and assess the legitimacy of knowledge when language is compromised by illusions and sight tampered by sensation? I exaggerate, but only a little, as I aim to perform the drunken hysteria of the play in an academic context. After all George is an associate professor of history at the college where his father-in-law is president. Condemning him to succeed on the patriarchal line, and failing miserably.

We are in the midst of the institution of knowledge and its dissemination, holding on to the morality of a foundational truth that in the name of quantification legitimates exclusions and determines what we teach and learn; how we assess; and what we consider important and worthwhile. To maintain this certainty, we keep to a historical and metric line, and within the frame of very local expectations, which we pretend are universally true, but which Aníbal Quijano derides as provincial, themselves a fiction of contingency dressed up in a globalizing language:

“Nothing is less rational, finally, than the pretension that the specific cosmic vision of a particular ethnie should be taken as universal rationality, even if such an ethnie is called Western Europe because this is actually pretend to impose a provincialism as universalism.”2

The delusions of a Western European and US, modernist universalism are visual. It is the eye as cultural practice and signifier that determines its relationship to things as objects that hold our gaze and that we hold through our need. They are ‘zuhanden’, at hand, as functional thing, as ‘Zeug’.3 Available for us, rather than with us. I say this not in an essentializing but in a very particular way. For it is not all eyes that see the world this way. And so it is not the eye, it is not vision, but rather it is a particular US-European visuality which as a local and cultural visuality determines what we see and how: what is, as Sara Ahmed puts it, in the foreground and what is in the background of a particular culture’s vision and thus instigative of its actions and informing its reality.4 These cultural eyes are the standard bearers of the real. Their vision is translated into measurements, and visualizations, that divorce it from the uncertainty of the contingent encounter. Thus, they sustain its view and entrain us in a cultural visuality.

We could see the world otherwise. And every way we see the world has social and political effects. Doreen Massey makes this point persuasively when in the first chapter to her book For Space from 2005, she compares the maps of Tenochtilán now Mexico City, drawn by the Aztecs and by the Spanish conquerors. Each focused on the same locale and giving us an entirely different view of the location. Thus, she reminds us that the vision of global space, the cartography of its territory and movement, “is not so much a description of how the world is, as an image in which the world is being made.”5 Visualizations do not measure and describe a certain world but generate the veracity of their own fiction, which becomes future’s reality. Their design is motivated by politics, ideology and desire, and the fear of losing certainty and ground, of finding things disordered and unreal, and not measuring up.

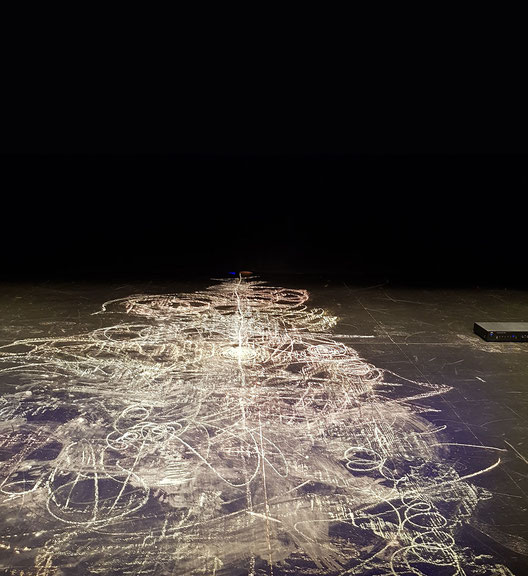

One response to the coercive fiction of this visuality is to find ways to pluralize what we see, and re-imagine how we live together with things rather than using them. The suggestion is to engage in listening to “direct” sound: i.e., to non-visualized, non-systematized sound; sound that is not the sound of a visual thing, or that is not listened to for its visual reference, but that is sound as an invisible and indivisible materiality. In this sonic state, things are not “this” or “that”, me or you. They are not zuhanden, available for me, but generate the in-between, and what we sound together. Such direct sound, as material and concept, as what we hear contingently, has a connecting logic, foregrounding relationships rather than things; and it has a voluminous dimensionality, appearing as a vague expanse rather than a concrete measurable space. Thus, direct sound refuses quantification but insists on the rigor of a contingent (listening) practice to facilitate understanding and finally evaluation, or at least description. Whereby the interpretative and evaluative practice that coincides with this listening remains skeptical of a priori language, seeing it as a means of visualization and a re-duction into a hegemonic knowledge regime. Instead, such listening hopes to stay “with the trouble”, staying with the fuzzy inarticulation of sound when it is not about something but when it makes connections and expands the field of vision beyond infrastructural walls and certainties.6

However, such listening does not endeavor to hear “sound for/in itself” – a concept that finds many different and also contradictory discussions in much sound studies literature. Instead, acknowledging the relationality of sound, this listening ‘practices’ sound as a portal or sensible access point to a vibrational world, where sound does not sound anything in or for itself, but sounds with everything and thus sounds a connecting logic. In this way listening makes thinkable complex interdependencies and reveals as deceit the idea that we might comprehend reality through separate categories and at a distance, when it is always already up close and entangled with everything I hear. This entangled, vibrational world is easily imagined through the action of clapping your hands. The sound we hear when listening to this action is not the sound of one hand hitting the other. It is not the sound of hands, neither left nor right. Instead, it is the action of two hands clapping sounding with everything else. The clap I think I hear as a separate entity, a nameable noise, is the sound of everything vibrating in its agitation, making the listened-to sensible as a connecting event: the room, furniture, bodies, carpets, windows, doors, sounding indivisibly together. Thus, it leaves me with the sight not of hands clapping, but of an indivisible space that in its voluminous dimensionality does not permit my gaze to hold on to anything in particular but forces me to sense a connecting sphere.

This indivisibly connecting sound of our clapping hands cannot be theorized conventionally, from a distance or according to a visual scheme: a score, a text, or a map. It cannot be reached by a visual cultural discourse because we cannot hold it in our gaze, but only sense it on our body that is listening as a body with: My sound is part of your clapping hands and thus has to be part of its theorization. Such a consciousness of being with creates an entirely different sense of reality, values and validities. As well as a different sense of subjectivity, of the collective and how we belong with human and more than human things. What is real then cannot be measured referentially, but is worked out contingently and from the midst of things being unavailable as stable definitions. We need to be with them, in time and space, to come to an understanding of the listened-to that includes ourselves as listeners and therefore problematizes the perceptual process and vis-à-vis, rather than simply what is heard. In this sense, such an engagement with the world through sound troubles the knowledge foundations of the west and the certainty of objectivity. It implodes distance as a legitimate means to get to knowledge, and demands the body, in its diversity, be readmitted as a witness and collaborator in the production and valuation of knowledge as plural and differently real. Thus, it insists on proximity as criticality, and on embodiment as a practical tool of a theory that listens with; and it suggests reciprocity and responsibility, since in listening with, any knowledge I gain is also a knowledge about me, my orientation, my subjectivity and my being in the world.

At this juncture, the desire to remain visual, and objective; to read and interpret, stands in contrast to a troubled contemporary condition, where complexly interwoven problems defy certainty and reject the ability to distance ourselves. We are currently at the tail end, or maybe just the beginning of a new wave, of a global pandemic, which in its viral reach and rebound demonstrates the interdependencies between cultural habits, social structures, economic opportunities, political governance and health outcomes. COVID-19 has shown that we are inescapably connected through the (viral) air we breathe, and that what we eat, how we travel, use resources and relate to human and more than human bodies, has an impact on public health. The pandemic reveals the deep entanglements between the climate emergency, scarcity of resources, consequent migratory pressures and ultimately their impact on social justice and public health.7 These present and increasing emergencies demonstrate the fatal facts of connectivity and show the fiction of visual boundaries, straight lines and individuation. The viral demands physical separation because without masks and walls we are not separate, but porous and open to contagion. Thus, it mocks the illusion of objectivity and distance which western science and scholarship is based on, and provides a view on a fuzzy sphere of co-dependence, permeability and the deceit of stable definitions.

In this context, the relational logic of sound, its capacity to re-vision the world through proximity and from the in-between, does not offer an inaccurate, trivially fictional or even mad and esoteric trope of exploration, easily dismissed. Instead, its very inaccuracy vis-à-vis given measures, its radical inability to confirm taxonomic categorization, and its ability to cross or rather ignore architectural, geographical, national, cultural disciplinary and so on lines and metrics, provide rigorous possibilities and tools to engage the complex entanglements of the contemporary. Because, listening, as a sonic thinking and methodology of research and knowledge is able to see the way its emergencies are entangled. It can grasp them not as separate issues or certain tasks, but as “wicked” problems that need the sensibility and capacity of (sound’s) relational logic to shift thinking and expertise towards the in-between, working on the “wicked” co-dependencies of contemporary crises from sound’s own “wickedness”.8

There is a longstanding discourse on the potentials of sound and the predominance of the visual, (e.g. Wehelyie, Cox, Cavarero, Kassabian, Ochoa Gautier, Schulze). While generating interest and intrigue for sound, their writing, just as this text, will always be folded back into a visual image of knowledge and of theory and read within its terms. The sonic has never so far managed to truly trouble the institution of visuality, to make it less certain of itself; to shake its foundational believes and dissolve some of its visible walls. Instead, sound remains forever emerging.9 When brought into the institution, it is mostly adapted and visualized: sound studies programs invariably perform a visual cultural studies of sound, exploring cultural and societal transformations as revealed or caused by the sonic, its performance or its technologies of recording or playback, etc. Or it is employed to expand musicology towards a cultural and situated listening to musical sounds. Both leave the visual methodologies and the commensurate ideologies in-tact. They do not bring us to listening but expand visual literacy towards the sonic. Thus, we come to hear visual realities anew, but nevertheless visually, and direct sound remains marginal, hidden in blind spots or deliberately ignored, and we remain unable to shift the knowledge paradigm towards the potential of relational and fuzzy possibilities.

The line of visual, white, and patriarchal knowledge is strong, straight and persuasive. But it is also violent and exclusive, a settler’s attitude, and symptomatic as well as causative of the Capitalocene.10 Given the urgent need for a different view if we are to solve the various emergencies of our time, we need to explore the capacity and promise of sound’s possibilities, to give us new pathways to pluralize thinking, and know with each other.

The practice of direct sound making and listening as a way to knowing otherwise, does not aim to open a binary. Instead, it aims to open the dominant to its contingency, its porous and unreliable body, its plurality and what things might mean together. In that sense sound making and listening, and the two are necessarily performed together to achieve response-ability: a hearing that is responsible for the listened to, is an actual and conceptual practice of the multi-sensory and the embodied. It does not stand in opposition to vision but opens it to its own possibilities, to challenge and pluralize a cultural visuality, to embrace, at this moment of crises, the connections the visual ignores and the voices it silences.

One way to achieve such a multi-sensory and connecting “vision” is through a sonic pedagogy and a transversal sound studies: that is a teaching and learning from the affective and the embodied, the relational and the contingent of sonic possible realities which enable a teaching and learning “for all students, no matter what borders they need to cross”11; and that is a studies that practices the knowledge of the invisible and the in-between, to develop a “sonic competency” as a connecting logic that equips us to engage with the complexly interwoven problems that describe the interdependencies of a viral world.

This is not an essentialized undertaking but a move towards a “multi-sensoriality” that does not stop at invisibility but senses it as a cause, to hear, smell, taste, see and so on differently, and to create a physical image of the world that troubles institutional certainties and the knowledge it builds from its representations.

The aim to trouble institutional knowledge foundations through listening is not just a game, but an earnest play. It is the serious performance of an embodied, feminist and decolonial listening that engages its own invisibility to re-vision and re-imagine how we see, and what can be true. There is a reason to the deliberate introduction of the unquantifiable. And if we are afraid of it, we should consider why, and what we fear to lose? And at the same time, we should ponder what we stand to gain, listening to the indivisible realities of a vibrational world.

1 My discussions here are informed by the1966 film adaptation, which is available to watch here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hlVyZ6cooxc/. If we listen to rather than watch this film’s rendition of the play, we can ease our focus off the individual characters, that stand as archetypes of society, gender, success, failure and identity, to abandon the binaries and oppositions, and come to hear how they are together and in their transforming nature, in-between, and get a different view on normative expectations.

2 Aníbal Qujiano, “Coloniality and Modernity/Rationality”, in: Cultural Studies, Vol. 21, No. 2/3, March/May 2007, p 177 (quote as per Quijano’s wording).

3 Martin Heidegger, Sein und Zeit, Tübingen: Niemeyer, 2001, p 71.

4 Sara Ahmed, in “Orientations: Towards a Queer Phenomenology”, in: GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, Volume 12, Number 4, 2006, p. 549.

5 Doreen Massey, For Space, London: Sage Publication, 2005, p. 4.

6 Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019.

7 A. Woodward et al., “Climate change and health: on the latest IPCC report,” in: The Lancet, Vol. 383, 2014.

8 These contemporary entangled emergencies can be identified as a “wicked problem” (see Karl Popper, Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge, London: Routledge, 1963; H. W. J. Rittel and M. M. Webber, “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning,” in: Policy Sciences, Vol. 4 (2), 1973, pp. 155–169), “because of the incomplete knowledge of effects and interdependencies, because it involves actors operating in different sectors and at different levels, because all possible actions have uncertain effects, and because they are intertwined with other problems in complex and, to a large extent, unmanageable systems” (Per Morton Shiefloe, “The Corona crisis: a wicked problem,” in: Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, Vol. 49, 2021, p. 5).

9 Jonathan Stern refers to Michele Hilmes’ text “Is There a Field Called Sound Culture Studies? And Does It Matter?” to suggest Sound Studies as an always emerging and never truly emerged discipline. (Jonathan Stern, The Sound Studies Reader, NY: Routledge, 2012, p. 3)

10 Here I refer to Dylan Robinson’s Hungry Listening, in which, distinguishing between settler and indigenous listening positionalities he outlines the concept and characteristic of “settler listening” as hungry, in that “it prioritizes the capture and certainty of information over the affective feel, timbre, touch and texture of sound.” (Hungry Listening: Resonant Theory for Indigenous Sound Studies, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2020, p. 38) Another point of reference her is T.J. Demos’ Against the Anthropocene, where he advocates against the term Anthropocene and for the “more accurate and politically enabling descriptor” Capitalocene, to critique the essentializing assessment of the human into one single type, which denies asymmetries and exclusions caused by patriarchy, coloniality and capitalism, and disables a more nuanced assessment of culpability. (T.J Demos, Against the Anthropocene, Visual Culture and Environment Today, Berlin: Sternberg 2012, p. 54)

11 Glen Aikenhead, “Border Crossing into the Subculture of Science,” in: Studies in Science Education, Vol. 27, 1996, p. 2.