Issue 2/2023 - Sharing Worlds

Sharing the World with Others

Interview with Elizabeth A. Povinelli and Cecilia Lewis on the Artistic Practice of the Karrabing Film Collective

On the occasion of their Vienna Secession exhibition, the Karrabing Film Collective presented their new film „Night Fishing with Ancestors” (2023). It lays out two radically different modes of encounter when it comes to coexistence, or “sharing the world”: one is the kind of exchange relationship that developed between the Indigenous population of the Australian Northern Territory and the Macassans from Sulawesi before white settlers came; the other is the brutal colonization by white conquerors like Captain Cook from 1770 onwards. Overcoming this particular past is a major objective in a lot of approaches that attempt a more equal and just distribution of “shared worlds”. The question raised by the work of the Karrabing Film Collective concerns the aesthetic registers that might best be suited for such an endeavor. Here, their use of overlays, superimpositions, sometimes also blurrings stands out, but also a certain documentary mode that pays heightened attention to environmental givens like rocks, sands, fish-traps and so on. This style has been characterized as “improvisational realism”1 (Secession catalogue, p. 78), operating in the space between violent colonial dispossession and the potentials of a newly gained autonomy or sovereignty. An implication of this is a specific focus on “survivance” and “endurance” – both aspects which have variously been pursued and enacted in their films since 2014. The following conversation touches on particular aspects of this approach as well on the underlying theorization of “geontopower” that Elizabeth Povinelli has laid out in her philosophical work.2

Christian Höller: An alternative to the standard Western historical model (the one of unilinear progress that has come under increased scrutiny) is the idea of an “ancestral presence”, a present shared with your ancestors, as it were. This seems to suggest a radically different, or even incompatible, worldview from Western, rationalistic or techno-scientific, perspectives. How can this “ancestral present” best be characterized or mediated?

Cecilia Lewis: Yes, the ancestors are still present. You can feel this when you go back to the land. The ancestors are there in a certain place and they sometimes can get angry with you. I can feel somebody watching and following me, but it doesn’t worry me because I know I am safe. One can feel the spirit in the body, or in sweat. If you don’t go along with that, a lot of things can happen to you. Like you can end up with a flat tire, or with a bursting radiator, or something falling down from a big tree. The ancestors are always right there, not just in this material way but in a spiritual way as well.

Elizabeth Povinelli: They are also there when it comes to time. White people say time just goes forward. But we go forward with the ancestors. We live with them. Like Cecilia’s sister, Angie [Angelina Lewis, member of Karrabing], always says: white people want to cut everything into past, present, and future – but ancestors embody all that at once. They are in all in these temporal modes at the same time, and it’s not like this is all very mystical, it’s not – it’s very material. I remember that some audience member asked Rex Edmunds [member of Karrabing] once at a screening if there isn’t an “old, old way” to save the planet. And he replied that the “old, old way” is in the now. It’s there right in the land, and one should try to make things that happened before happen again.

Höller: A very significant figure in “Night Fishing” is the white settler, or conqueror, played with extraordinary intensity by Elizabeth Povinelli. This figure appears to embody various facets of colonialism, from James Cook onwards to neoliberal adventurers like Elon Musk who is searching for sources of “clean energy”. At the same time, there’s a zombie-like quality to this figure and I wanted to ask you about the background of this allusion to the (fictional) horror genre – when the effects of extractive capitalism are actually quite real and catastrophic.

Povinelli: The white zombie comes is three characters in “Night Fishing with Ancestors” – Captain Cook, a mid 19th century explorer, and a techno-bro looking for clean energy. The figure of the zombie continues from our previous film, “The Family and the Zombie”. That film set in the future, playing on the history of Elon Musk. In it a family of future ancestors are stalked by a remnant white person who now eats batteries and rusty cars.

Lewis: Another background is the “mine race” which is happening right now, concerning for instance the search for lithium in Australia. The water from one of the mines runs into a popular crabbing and fishing area and ends up right at the beach. The last time I went there in order to get crabs, there was this long oil spill in the mangrove. There is lot of waste water that is polluting the area.

Povinelli: The reason why Captain Cook is turned into a zombie in “Night Fishing” is that the kids who participate in the film-making had such a fun time shooting “The Family and the Zombie” they wanted to continue the game. We wanted to continue with the zombie theme because this isn’t a figure that will arrive in the near future – the zombie already came. It’s not a coming catastrophe, it’s an ancestral catastrophe.3

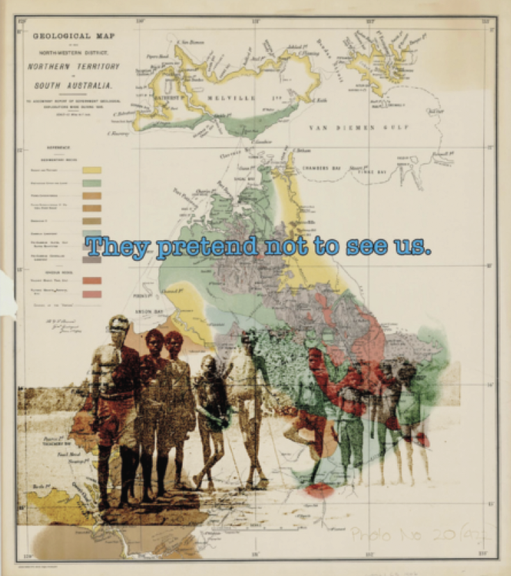

Höller: One of the wallpaper inserts in the exhibition reads, “White people only want what is valuable in their eyes”. Another “artistic intervention” says: “The pretend not to see us”. Would you consider this as the main blind spot of what you call “toxic late liberalism”4? Or what other major factors would you subsume under that kind of toxicity – not speaking of the very concrete extent of poisonous substances left behind in the trail of extractive exploitation?

Povinelli: The toxicity is of course very real We always say, why can’t white Europeans understand that if they put poison in the land, the poison is and remains in there. The government usually pretends that they know how to fix a problem, or that for instance we’ll go fix climate change by having battery energy. But what does this mean? It’s again pretending that making batteries is not producing more poison. They might say, ok, some particular step in the past was wrong – but then they do it again. And this is repeated over and over again.

Lewis: The governments for instance sends people to our land to test the water that runs down to the creek. But if there is a leak of poisonous substances, they should notify the community first because we only live a few kilometers away from the mine. It’s like saying, there is a boundary, but let’s ignore it because these are just indigenous people … Usually, they’ll go ahead and do what’s only best for them.

Povinelli: They pretend you’re not there and also, that the poison’s not there. This is a constant form of almost psychotic disavowal.

Höller: Speaking of the blind spots of late liberalism, a major, indeed quite formative distinction in your work is the one between the coming catastrophe VS. the ancestral catastrophe. Whereas most Western liberal democratic systems are slowly arriving at the insight that there’s possibly an apocalyptic event lingering on the horizon (the uninhabitable earth), for colonial and Indigenous populations this catastrophe has happened a long time ago. To put it naively: Shouldn’t one try to constructively combine these two ground-breaking insights? Or try to build an “assemblage”, derived both from the histories of colonization and slavery and the newly gained knowledge of planetary heating?

Povinelli: The problem with the ancestral catastrophe is that it keeps happening and building up, which is not ideological but very material. First, they put toxins in the soil and extract all sorts of stuff, which continuously builds up the land. So, the ancestral catastrophe isn’t in the past, just as the coming catastrophe isn’t in the future. The experience of climate change that the West is now undergoing, or the realization that we’re living in a toxic world and that plastic is everywhere, isn’t something new or a development that’s suddenly happening to us. Rather, it’s the West having to experience the practice of their capitalist colonial history as what it is – a form of sedimentation. Instead of time, we should speak in terms of sedimentation and movement – worlds and routes5: how different worlds were manufactured through the movement of materials and matter, toxicities and purities. Yes, these movements happen over “time” but they are radically present.

Höller: An important role in the theorization of the coming VS. the ancestral catastrophe is the kind of abstraction that is operating in notions like the “whole-world” (“tout-monde” in Édouard Glissant’s terminology), or concepts like “earth” or “Gaia.” You starkly contrast this with more historically-based notions like “the conquered earth”, described in detail by authors like Aimé Césaire.6 Again, to follow up on my last question, shouldn’t we look out for a potential mediation, or at least a constructive kind of dialogue, between these opposing worldviews?

Povinelli: It depends on what we mean by abstraction. Trying to do is to find the concept that can be applied anywhere at any time irrespective of its location within a social political ecology, is a form of colonialism in the sense that it invades all spaces even as it claims to be free from any social relation. That’s why, at Karrabing, we say “from here, based on such-and-such relations, this is the kind concept we need.” The question is, are we looking for a concept that anyone can use anywhere, or do we always, like Édouard Glissant, think about the relationality of the concept work? This also applies to my own concept of “geontopower”. From the point of view of Karrabing, this form of power is central. But perhaps, if you are theorizing from the Black Atlantic7, “geontopower” might need to be put in relation to other concepts. The colonial invasion of the world did not create one social political-ecological Relation. It created multiple ones. Thus, conceptual work also needs to understand itself as working within created multiple relations that might make political work and political solidarity difficult or awkward. For instance, Karrabing seek to strengthen their kin relations to their more-than-human world – animals, winds, reefs, etc. But, critical working in the Black Atlantic might seek to find a different kind of humanism first and foremost.

Höller: A central theme in the Karrabing approach are environmental concerns – the toxic “tailings and trailings”8 that extractive capitalism leaves behind in former colonial spaces like Australia. How do they differ from strands of Western environmentalism – both historically (when you look back for instance at groundbreaking work by Rachel Carson, Gregory Bateson and the like) and contemporarily (when you think of climate activism like Last Generation or Extinction Rebellion)?

Povinelli: Obviously, we need these strong climate activists. They are crucial. What interests me a little more, at the moment, however, is the struggle of Western progressives to find a way of belonging to a place. Karrabing and other Indigenous people have strong relations to specific places with obligations about who and how they should be properly attended to. It is not that Europe lacked forms of place-belonging. I know this from my own family – Povinelli, a name that emerged in a small (now) Italian Alpine village, Carisolo, in 1480.9 Like other villages in the region, from the 12th century to 1805 when Napoleon invaded, they were given the powers to self-organize their common lands. This wasn’t a democratic commons – it was based on principles of mutual obligation between vicini (local families) and the exclusion of forestieri (nonlocals). With the rise of liberal individualism and the nation-state, enlightenment cosmopolitanism, and capitalist private property, the dynamic of white rootlessness and reactionary nativism set in. So, the question for many young European and ecologically-oriented progressives is – how do I belong to a place in a nonfascist way – or can people belong to a place in a way that demands that others who enter must abide by local obligations. This is of course central to how Karrabing belong to a certain places. So, to get to the question, can climate activists and ecologists learn how to belong somewhere without being fascist? In this respect, it’s not surprising that a lot of the first ecologists in the US were racists. They pretended not to see Native Americans – it was like saying, we’re gonna save this country, but the people who belong to that land are not allowed to go there.

Lewis: Like lot of First Nation people who have to ask for permission to go to their land and hunt there. It’s the same thing but in a different way. The problem with white ecologists is that unless indigenous people are doing things their way, they’re not interested in indigenous’ relation to the land.

Höller: Underlying your critique of Western liberal epistemologies and ontologies is a fundamental re-conception of power. In short, not only Foucault’s biopower should be dramatically recast but also the more recent revision of the human–nonhuman distinction since they are all (like most Western philosophical concepts) based on the much deeper distinction of life and nonlife [what you call “geontopower”].10 When it comes to undoing this tradition, is the objective to bring “nonlife” to “life”, so to speak, in order to undermine this distinction? Or what would a profound unmaking of “geontopower” look like?

Povinelli: The division between Life and Nonlife is a very old Greek distinction, based on the idea that Life is that which has the potential to be born, to reproduce and to die. Western metaphysics (Dasein, biopower etc.) and the epistemologies (biology versus geology, for example) depend on this division. This thought was, however, weaponized during the colonial period. People were placed on one side or the other – whether they were like stones, inert, or how much they had potentialized themselves--to legitimate the destruction of certain worlds. This weaponization of a metaphysics of existence is the toxic interiority of liberalism and capitalism. It is the ground and matrix of biopower. The main question is: Do we take non-life and mobilize it as the more important or leading concept? Here, Foucault’s thought is still useful. He noted that one could not fight the organization of power by choosing one or the other side in its logic. One had to choose neither. One had to struggle in the space of the otherwise.

In critical theory, one of the ways in which people are reacting to the shaking or collapse of geontopower – the separation of Life and Nonlife – is focus on the entanglement of existence. But I think we need to be careful not talk about entanglement in ontological, or going back to our above point, abstractly. If we start with the claim that everything is entangled then once again, we are avoiding the sedimentations of colonial history. For me, that’s just replicating the problem. Again, we should focus on sedimentation and distributions, or “routes and worlds”. The West terraformed the world based on the geontological distinction of life and nonlife. It pulled material out of Africa and Australia to build Europe. To really critique geontopower is not to pick one side but to say, what are the material, sedimentational worlds that have built from invasions, and how do we recompose these worlds.

For instance, in “Gaia and Ground”, I describe how people found out that Belyuen [part of the Australian Northern Territory where Karrabing live] was a dumping ground for asbestos. Why did they find out? Because the government was opening land for, primarily, white housing development. I am interested in how those who have benefited from this kind of toxic distribution react. A typical response is, okay, we’re going remove it, we’re going replace it and we’re going restore it. But where are you removing it to? Where are you going shove it? And what are you restoring it with? You have to dig the new stuff up from somewhere.

Lewis: You don’t wanna say, with respect to the copper pipes or whatever good infrastructure you have, I’m gonna rip them outta my house and give it to you. You suffer and get cancer; you suffer and die. Go ahead, your turn to take some of the poison.

Povinelli: When you take something poisonous out, you have to put it somewhere, you’re have to replace it with something, and you have to bring that replacement from somewhere. In this respect, it’s justified to claim, take the marble that’s built up here and send it back; and you pay for bringing it back!

Höller: In order to undo “geontopower”, does the clue maybe lie in a kind of middle or common ground between life and nonlife – in “forms” or “regions of existence”,11 that at first sight might not have a lot of analytical criteria in common (although for instance the “personhood” of rock formations or rivers is gaining more and more currency today). Is it possible to get a better grip on this by the postulation of a newly conceived intermingled ground where the old distinctive criteria (like life and nonlife, human and nonhuman) collapse?

Povinelli: That’s the thing. You don’t choose one or the other, or mingle the two. Because if you do that, you’re assuming that they still exist. You’re taking them and mingling them. But they don’t exist. They’ve been created.

Höller: So, you should throw those categories out and invent new ones …

Povinelli: Yes, but in a material, sedimentational way – a focus on the “routes” of concepts and matter. Not in the abstract, “everything’s entangled” kind of way. You don’t first ask, what is everything, everywhere, and then look at the particular within this everything/everywhere. Instead, you start with material relationality and then try to act relationally. Karrabing to me is family, but I’m treated differently because I’m white. No matter if these are my great-grandkids or not, sometimes I have to go out first and take care of certain things. Like for instance with the passport person: “make Beth show up first because the white face will help get us through.”

Lewis: You get less discrimination by letting the white person do the legal work.

Povinelli: We’re together in our difference. You have to a bifocal point of view – and perhaps have the difference subtending the common first and foremost.

Karrabing Film Collective – The pretending not to see us …, Secession Wien, 28. April – 18. June 2023.

1 See: Massimiliano Mollona, Kunst ist Wandern durchs Gras, das flüstert. Karrabing Cinema als Art Commons, in: Secession Wien, Karrabing Film Collective. Köln 2023, p. 85ff.; see also: https://karrabing.info/karrabing-film-collective

2. See: Elizabeth A. Povinelli, Geontologies. A Requiem to Late Liberalism. Durham/London 2016.

3 See: Povinelli, Between Gaia and Ground. Four Axioms of Existence and the Ancestral Catastrophe of Late Liberalism. Durham/London 2021, p. 49ff.

4 Ibid., p. 36ff.

5 Povinelli, Routes/Worlds, e-flux journal #27, September 2011; https://www.e-flux.com/journal/27/67991/routes-worlds/

6 See: Povinelli, Between Gaia and Ground, p. 63ff.

7 See: Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic. Modernity and Double Consciousness. London/New York 1993.

8 See: Povinelli, Between Gaia and Ground, p. 127ff.

9 See: Povinelli, The Inheritance. Durham/London 2021, p. 71ff.

10 See: Povinelli, Geontologies, p. 4ff.

11 See: Povinelli, Between Gaia and Ground, p. 3ff.