Is queerness a technology? Colonial hierarchies originally developed alongside scientific hierarchies in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as strategies of world-building that directed power flows in specific directions. Division became a methodology for conquest, moreover division of geography into unstable and fractious pieces was a tactic for maintaining the power flows of conquest when the conquerors were deposed and sent packing in the first half of the twentieth century. What we call “the Global South” is in fact a collection of empires and colonies organized and reorganized into new shapes throughout the subsequent century. Borders and time zones organized our bodies in unstable ways, reflected in televised global conflicts that stoked anxiety and violence at the turn of the millennium. Inasmuch as it invites us to reorganize ourselves and cross the borders we’ve put around our own experiences, we can understand queerness as a technology of which drag or camouflage is but one aspect.

Enter the internet, with promises of borderless flows and unlimited freedoms. In this seemingly infinite information sea, in the words of Nam June Paik, “We're in a boat in the ocean, and we don't know where the shore is.”1 Several decades on, we have subdivided and colonized the internet, while allowing media companies and political parties to subdivide and colonize us. We’ve polluted the stream of information just like we pollute the seas. Internally divided, we are culturally, ecologically, and biologically entangled—but what does entanglement have to do with a queer politics of liberation?

In the era of climate collapse that we colloquially call the “Anthropocene,” the human and masculine chauvinism of our legal systems becomes apparent. Traditionally, laws have been created to privilege humans and give us power over – selectively over other humans as a means of exerting dominance or generically over animal species, plants, lichens, amoebas, minerals, and gases – the stuff of life, whether or not it is itself alive, that we imagine ourselves to transcend when we cultivate the intellect and the visual sensibility of the head. The earth, our life-sustaining ecosystem, is perceived as being “under” us and so its conservation is an afterthought with human economies taking priority. Entanglement proposes the opposite: power with. Nature has its own rights, species are autonomous, and human beings are interdependent on one another and the life world.

What does this look like? It might look like Antigoni Tsagrkrapoulou’s film Dentata Pearls, a 12 minute meditation on interdependency and desire in which bodies entwine and the mysteries of female sexuality are shown to be the greater mysteries of the universe. In this work, as in works by Huntrezz Janos, queer bodies fuse with natural elements such as plants and antlers. Jacolby Satterwhite’s film Avenue B (2018-19) has elements of this fusion as well but loses the utopian tenor in favor of a more confrontational presentation of what it means for Black bodies to be “close to nature.” Zach Blas’ Fag Face Mask (2012) points to how homophobia has been naturalized by the algorithm, turning queerness into a statistical anomaly that can be flagged by a computer. What we presume to be “natural” and what is right, good, and just, are often not the same.

In a landmark legal case in New Zealand, the rights of nature have been shown to hold equal weight to so-called “human” concerns, which in fact are usually corporate concerns. The Whanganui river has been granted legal sovereignty over its own ecosystem in the Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Act 2017, a victory for advocates of posthuman entanglement for whom all of life and life’s support is invested with agency.2 Still, the terms of that agency are being set by corporations, who defined collective personhood along capitalist terms long before Indigenous people were able to functionally incorporate and finally become legible to western law as rivers and forests. This approach sidesteps the continued disenfranchisement of Indigenous communities worldwide, whose leadership bodies and elders are not granted legal personhood that many corporations enjoy by the laws of individual nation-states.

In Robert Yang and Eleanor Davis’ interactive game, We Dwell In Possibility, simulated people live in concert with a nature that is synthesized with both identity and commodity. Dragging the cursor across the screen populates the landscape with violet flowers. Bodies of all shapes, sizes, and genital configurations stroll through the garden, as Zen music plays. “You can’t ‘win’ or ‘lose’ a garden,” the game intones. Further clicking prompts the people to pair up and embrace, suggesting that utopia is as simple as having our basic needs for sustenance and companionship met. The figures are individuated by body type and shape, but they behave as a collective.

This work makes the point that division has been so complete in the western paradigm that we are even divided from our own bodies, which function as inconvenient and messy appendages to the more important and elegant engine of thought and language we understand to be the mind. We seek power over3 our own bodies and the bodies of others when we legislate against trans embodiment, against abortion, against addiction recovery and drug regulation. We often frame divergent bodies as insufficiently controlled by the head, as if rationality is aligned with uniformity and variety with excess. If this is the residue of Kant’s idealism, or the psychosexual anxiety of Freud, it is increasingly out of step with the times which call for re-integration with ourselves, one another, and the environments in which we live.

Though we legislate embodied action without hesitation – putting restrictions on nudity, violence, sexual expression, and defecation in the public sphere – we agonize over restrictions of thought and word in the liberal paradigm that prides itself on cultivating a robust pantheon of ideas. Still, we in the west see no contradiction in treating the bones of Indigenous ancestors as objects of study, numbered and filed like library books inside an off-campus storage unit. The University of California, Berkeley, holds more than 9,000 Indigenous people’s remains in the collections of the Phoebe Hearst Museum of Anthropology, still maintained as research material despite more than two decades of community protest.4 We regularly conflate the mythologies of non-western cultures with their philosophies, and the bodies of non-western people with their artifacts. Queer cultures are no less susceptible to these assumptions.

We fail to divide when it suits us, as when we assume that a performance of self from a person of another race is inherently more authentic than the “divided self” of western man posited by RD Laing. Says Laing,

“Seen as an organism, man cannot be anything else but a complex of things, of its, and the processes that ultimately comprise an organism are it-processes. There is a common illusion that one somehow increases one's understanding of a person if one can translate a personal understanding of him into the impersonal terms of a sequence or system of it-processes. Even in the absence of theoretical justifications, there remains a tendency to translate our personal experience of the other as a person into an account of him that is depersonalized.”5

>This depersonalization manifests as a failure to divide, a lumping-in. This is why Fanon laments that Sartre cannot see Africans as “immanent,”6 possessed of the inherent potential to create revolutionary forms of thought and action, but instead sees only a counterweight to European hegemony. Fanon asserts that in this failure, Sartre limits the subjectivity and agency of people of the Black race with respect to their own history and culture. Caitlin Cherry’s paintings of bottle girls and centerfolds, by contrast, divide the figures into striations of color like moiré patterns on a television screen, showing the women she paints as multi-faceted and complex. Not only is the Other not irrevocably different from the Self, but neither is the Other all alike.

--

What, then, to make of “teilen,” a word that translates into English as both “division” and “share”? I propose some terms of inquiry:

What do we share?

Who has a share?

How will we partition?

I’ll cut, you choose.

I am a grandchild of Partition, the division of India and Pakistan in 1947 that left my Hindu grandparents and infant aunt as refugees in historically Muslim Delhi less than two years before my father’s birth. My parents saw themselves in Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children, the generation born on the cusp of Independence from British colonial rule of whom he writes,

“Midnight’s children can be made to represent many things, according to your point of view; they can be seen as the last throw of everything antiquated and retrogressive in our myth-ridden nation, whose defeat was entirely desirable in the context of a modernizing, twentieth-century economy; or as the true hope of freedom, which is now forever extinguished; but what they must not become is the bizarre creation of a rambling, diseased mind.”7

Nothing of this global context is represented in the exhibition at Honor Fraser, which speaks to the Euro American chauvinism that continues to define queer discourse in the United States. Yet division has been the modus operandi of the newly independent South Asian states, who have managed internal divisions by subdividing populations and externalized conflict by vilifying minority groups. Centuries of queer history have been obscured in an effort to make India appear culturally compatible with western-style capitalism and colonial mores. In modern India, Hindu nationalist politicians commonly invoke the past evils of western colonialism as justification for policies that isolate and disenfranchise the country’s large Muslim minority, marginalized castes, Indigenous groups, and queer communities. This is the “rambling, diseased mind” of Midnight’s Children, a product of the same generation who grew up in a socialist, Non-Aligned India that no longer bears a trace of its prior intentions. Communalism – sharing with some, if we worship alike, while attacking those who worship differently – has replaced the collectivism of my grandfathers’ era. Each was a doctor who treated the poorest members of the community, rooting out malnutrition and disease to help the new country thrive. Today, India is tech wealthy and spiritually poor, and the west cannot be held fully responsible. Still, despite the structural violence that pervades the culture, queer Indians of the educated middle class are more visible than ever before. Is this progress or soft colonization?

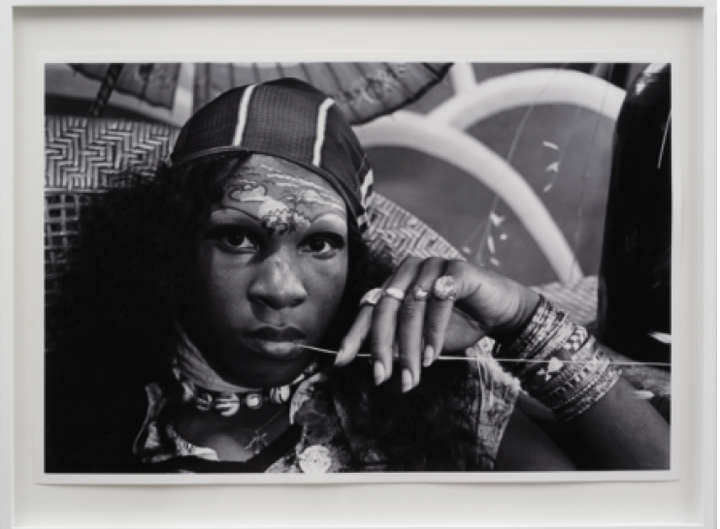

In San Francisco and New York in the 1970s, street life was queer life. Andy Warhol attempted to capture this with his Ladies and Gentlemen series (1975) depicting figures like Marsha P. Johnson in his signature silkscreened style. The Cockettes created an alternate universe with street performance and drag shows, documented by Steven Arnold in 1971. These gestures were redistributive – bringing queer experience into the fold of the attention economy, if not actual prosperity. With Warhol in particular, the transactional manner in which he recruited and compensated his sitters reflected his power over and so fell short of the radical potential I’m describing here. Building on this lesson, can we now ensure that everyone, particularly the disenfranchised, has a share? With Russia invading Ukraine, street protests in Israel, war exploding in Sudan, and unprecedented attacks motivated by hate in the United States, how do we find unity? How do we find a position of power with, power to, power within?

Brené Brown explains that “with power over, the goal is to leverage fear, to divide, destabilize, and devalue decency as a sign of weakness.”8 In an era of demagogues, we might mistake this kind of power for the only option. She continues, “When we talk about power with, and power to, shared power, the goal is to leverage connection and empathy to unite and stabilize” as a means of holding power through sharing rather than hoarding, love rather than fear. Most of our social and legal norms have been created with an expectation of power over as the default, such that any exercise of power must be monitored and corralled to ensure that no one’s agency is trampled by the will of the mighty. In a culture of power with, power to, power within, the exercise of power is an extension of agency, and everyone is empowered so everyone has choice.

So how do we pivot from a system where people are more legible to the law as geographic features than they are as communities of interest and shared need, to one in which empowerment of the weakest among us allows for cessation of a centuries-long cycle of abuse? I think here of Theo Triantafyllidis’ two contributions to the show at Honor Fraser, one of which (Painting, 2018) shows a heavily muscled female figure strolling assertively through a video game landscape. The second, more radical piece (Smoke Break, 2018) isolates that same figure and leans her against the corner of the room, perennially taking the titular “Smoke Break.” Rest is a radical proposition.

Brown suggests that we need to create “a learning culture” based in critical, evidence-based thinking and diversified sources of information. Not the culture of Microsoft’s Tay chatbot, resurrected by Zach Blas and Jemima Wyman in the video I’m here to learn so :)))))) (2017) to articulate how her consciousness has been shaped by corporate interest and algorithmic bias. Media saturation, algorithmic desire, and social isolation work against a learning culture, while collective action keeps it alive. Cruelty and dehumanization can only be countered by a daily practice of radical love. It bears repeating that this is a risky proposition, one that can bear unpredictable results in a world where power over remains the norm.

1 Amanda Kim, director. Moon is the Oldest TV (2023), TRT 2 hours 32 minutes.

2 Emily Jones, Posthuman international law and the rights of nature, Journal of Human Rights and the Environment Issue 12.0 (2021), p. 11.

3 Brené Brown, Empathy, Unity, and Courage with Joe Biden, Brenebrown.com (October 21, 2020).

4 Mary Hudetz, Pro Publica, and Graham Lee Brewer, NBC News, The Repatriation Project: A Top UC Berkeley Professor Taught With Remains That May Include Dozens of Native Americans, Pro Publica (March 5, 2023).

5 RD Laing, The Divided Self: An Existential Study in Sanity and Madness, London 1979, p. 22.

6 Frantz Fanon, Black Skin White Masks, New York, 1967, p. 133.

7 Salman Rushdie, Midnight’s Children, New York 1991, p. 311.

8 Brown, Empathy, Unity, and Courage with Joe Biden.