Jussi Parikka is a media theorist and professor of digital aesthetics and culture at Aarhus University. At the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague, he leads the research project “Operational Images and Visual Culture: Media Archaeological Investigations.” His book “Operational Images. From the Visual to the Invisual” has been published recently. A conversation about images beyond representation, machine vision and a new visual regime.

Sabine Weier: Your forthcoming book is about “a needed shift in emphasis to the operational

Image,” as you state. Why is this shift important now?

Jussi Parikka: We need to adjust the way we think about images and visual culture by focusing on the operations that produce visuality – by shifting from analyzing images to analyzing optical infrastructures and logistics, software and data. Currently, we see many discussions around contemporary AI image production and platforms of prompt generated imagery. This imagery isn’t interesting in itself, but as a particular platform of creation. What procedures and automations and other forms of logistics operate here? What sensing apparatuses that are not necessarily producing images are operational? What is the notion of operation at work here? A transdisciplinary perspective helps to frame these questions. Sensing and imaging instruments are often being discussed within the history of science. The book and research project are additionally informed by media and photography studies. This approach not only helps to frame these questions, but vice versa also enables a better understanding of our photographic culture.

Weier: The concept of the “operational image” was first developed by Harun Farocki two decades ago, in texts and essay films with a special focus on the role of image technologies in the military-industrial context. You’ve outlined a much broader research. How do you define the operational image?

Parikka: The term “operational image” is beautifully tautological: operational images operate. These operations include different possible forms such as targeting, analysis, prediction, gridding, and logistics, for example optimization. When we ask about operations at the fringes and thresholds of imaging, certain terms take precedence here, such as laser scanning such as lidar, which has become a standard operation in mapping architectural or urban environments, for instance. A key interest for me are environmental imaging practices such as remote sensing and hyperspectral imaging. Imagery of the Anthropocene is often considered in photographic terms, partly due to the famous photographs of the Earth, taken from space since the 1960s onwards. We know this story and these images well but the more interesting ones are less seen – remote sensing imagery that in large quantities started to photograph and in other ways sense the planet producing this extensive archive that also is central to environmental management from understanding landuse to weather patterns to much more.I’m interested in how the familiar photographic imagery juxtaposes with the materiality of the planetary in relation to chemical, territorial, liquid, or other forms that actually form the base on which we understand climate change, land use, the biodiversity crisis, and such. Another particular interest of my research is the notion of “capture” as part of image operations. Images have early on been recognized as a particular form of capture, not just in the representational sense, but as particular data points, so they played a significant role within predigital computational practices.

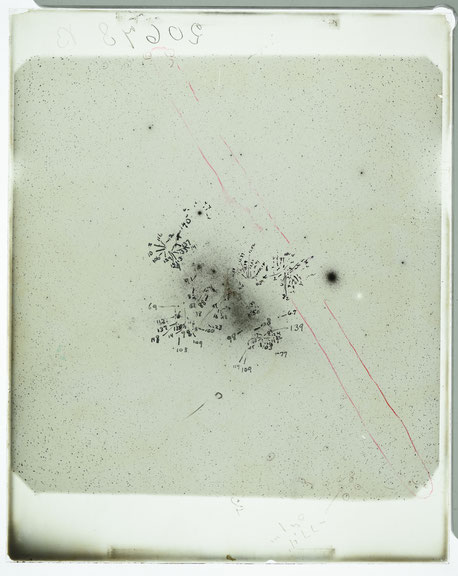

Weier: In the introduction to your book already prepublished on e-flux and titled “Between Light and Data”, you dig deep into the early history of photography and nineteenth century astronomy. You introduce Henrietta Swan Leavitt’s photographs on glass plates made to measure distances across outer space as an early example for images that become operationalized for data analysis.

Parikka: Those early models of sensing technologies as used in astronomical imaging techniques from the late nineteenth century onwards are an example for how massive scales of astronomical light were being condensed on glass plates. Images and data merge. This was a predigital computational event that included a lot of the processes that we now also understand in relation to remote sensing. Computational techniques were “discovered” in these early photographic practices, a kind of computing through photographic plates, an early nexus of computing and calculating in relation to photographic images. This was mostly scientific labor done by women, like in the case of Henrietta Swan Leavitt, especially in the cases I’m looking at from the Harvard archives. You could find similar cases in different national contexts too. Looking at other institutional practices like astronomy was also important to me to not just continue the military-masculine style of narrating the history of technical images.

Weier: Since Farocki’s pioneering investigations, the concept of the operational image has been mainly explored in the field of contemporary art and art theory. These projects are an important resource for your research. How are operational aesthetics explored in the field?

Parikka: Many of these artistic projects question how we deal with the contemporary obfuscation of complex machinery or large scale infrastructures. And they explore possible relevant proxies through which the sensing and mapping processes take place, whether it is a computer screen or a human operator or something else. My own collaboration with Abelardo Gil-Fournier on the video essay “Seed, Image, Ground” (2020) for the Fotomuseum Winterthur has been instrumental in terms of thinking about images through images. The work investigates aerial operations that redesign landscapes, cities, and fields; much of the imagery reminds of military contexts but also agricultural operations come to play as central of a role. In some cases the two are indistinguishable.

I’m particularly interested in artistic practices and discourses that feed into the question of what is at the threshold of visibility. I reference established projects and theories in the field such as Trevor Paglen’s or Hito Steyerl’s, but also many others. Rosa Menkman’s interesting ongoing project on resolution studies, for instance, that deals with “Impossible Images” that linger on the horizon of visible/invisible, visual/invisual, like the iconic first black hole image. I’m also really interested in projects that investigate environmental and remote sensing and big data infrastructures. A great example is Geocinema. Their research and film essays address logistical operations and sensing practices and the ways in which they are materially reformatting the world. Also a lot of Forensic Architecture’s work could be seen to be exactly of this spirit, because of their way of framing the epistemic image-complex by mobilizing images for the investigative work. Within that complex, images describe particular relations that can have impact on legal or social consequences but also how they mobilise new ways of reading “environmental data” is fascinating.

Weier: Some of these projects work with ideas around the conceptual fields of "visible" and "invisible. You also put the pair of terms prominently in the subtitle of your book.

Parikka: I work with Adrian Mackenzie’s and Anna Munster’s notion of the invisual that revolves around the paradoxical question of what is an image that is not a register of visuality anymore and instead works in the multiplicity of computational events that do the work of seeing on our behalf. This is somewhat different from invisibility, at least if we think of invisibility as something “at the moment not visible”, right? We easily think of invisible as something that is temporarily off the scale of visibility - a world that is already given that is just not visible in this moment. Of course, invisibility has an interesting history in photographic practices such as scientific photography. But there is a whole new regime that escapes the logic of visible/invisible. Computational processes reframe the notion of visuality in relation to to various scales of units at play: images are not so much seen as they are processed in massive quantitaties, as they are patterns for large computational infrastructures, and as they come to play a role in a variety of invisual operations. This applies very much to how images feature in AI infrastructures. For good reasons, Critical AI and data discourses have focused on understanding how particular algorithms and thus models of the world are being trained and how these models then reframe how the world is being sensed. Seeing is disclaced onto the computational operations of training, modeling, and a plethora of things that takes place in computer vision.

Beyond AI, I am interested in the book in asking what sort of sensing – and methods and concepts – apply beyond visible light. Think of even simple examples like infrared or ultraviolet light. Since the nineteenth century, these spectra of light were integrated in all kinds of apparatuses of sensing military and scientific apparatuses for instance. And here is the question: if the humanities – art history, visual culture studies included - have mostly focused on the visible light spectrum, how can we cultivate the broader insight into invisible and invisual spectra of culture alongside the many political and social questions that emerge with that refocusing.

Weier: Invisibility also plays a crucial role in the war in Ukraine. For instance, Ukrainians stopped sharing images of the public space on social media to not provide the Russian military with strategic information. Have you made any observations concerning operational images in relation to current Russian warfare?

Parikka: The war is an example of how observational events happen in registers of all kinds of examples of signal warfare that move from human perception and visibility to hyperspectral visibility in remote sensing alongside all kinds of automated systems. Naturally, this also includes searching for for signals through patterns in social media behavior –one example of this broader context of patterns that has moved beyond the image surface to the platform space of data. Anything can become a trace for something else, anything can become a proxy. Any image surface is a data surface and any data surface can become a targeting surface. Operational images help to maneuver such worlds of images, data, signal intelligence, as well as how power functions in and through invisuality.

Weier: How will these and other operative image infrastructures inform our near future?

Parikka: One way to answer would be to say there will be more of this – business as usual: automation and more comprehensive integration of AI systems into all sorts of operational spheres of life from work to security. What I am though interested in, and as a response to your question, to read it literally: images predict. I have spoken of this in earlier context as the “thousands of tiny futures” that are fabulated, imagined, governed through the expanded notion of the image: predictive technologies, simulations, scenario building. We are constantly already in the space of multiple futures from climate models to the microseconds of prediction that machine learning enhanced computer vision is using in different robotic or other systems. Such multitude of times that include real-time systems and image-based multiagent simulations are really interesting not as your traditional “futurism” but as these calculated mini-futures, mini-futurisms. These represent the sort of operative futures that our contemporary image worlds are creating and that we are inhabitating.