According to Michel Foucault, already in the 19th century there was an »infinitely minute web of panoptic techniques.« In the 21st century the situation is aggravated, as we are coming to a »novus ordo seclorum« of an all-present, all-seeing total surveillance. With the so-called »war on terror« and the American »Patriot Act,« which allows the Department of Homeland Security to wiretap land phones, cell phones and internet; Britain’s streets covered with over four million CCTV (closed circuit television) cameras; global satellite surveillance; and biological surveillance (biometric IDs), it is clear that the vision of a new world order is in fact a vision of a new global mass surveillance down to the molecular level.

The vision of total surveillance sprang from the prison panopticon model and military surveillance, both in its narrative and structure. The panopticon was a prison model designed by Jeremy Bentham in 1785 as a concept that could fit any institution, a schema that spread throughout the social body as a general function that became operative in prisons, schools, military camps, factories, hospitals and more. The most important part of the panopticon is the central point of the structure, the watchtower which can see every subject of the facility while being itself invisible – one can see the observing gaze but not who is behind it. The panopticon gives the authorities God’s point of view, the omnipotent, omnipresent gaze (panopticon means literally »to observe all«) of a monotheistic, invisible God. The panopticon has the disciplinary power of mass interpellation through the power of surveillance. The prisoners are always kept aware of the »big other’s« (the symbolic order’s) constant gaze and must »behave« at all times, while at the same time the central eye of the structure serves to observe and extract from the inmates a body of knowledge.

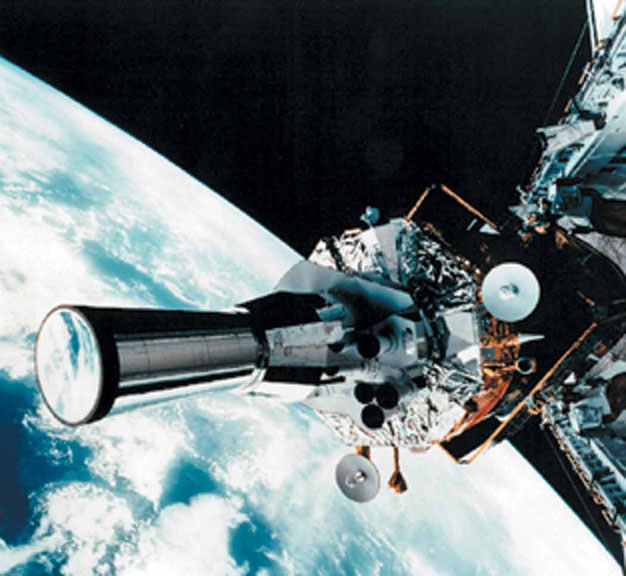

Already in the 6th century BC, Sun Tzu wrote in his »Art of War«: »Warfare is a matter of deception, of constantly creating false appearances, spreading disinformation, and employing trickery and deceit… The corollary to being unknowable is seeking out and gaining detailed knowledge of the enemy through all available means.« As Paul Virilio wrote, warfare is always »a game of hide-and-seek.« The army always aspires to be in a panoptic position, to see everything in the battlefield and behind the enemy lines, yet remain invisible. The panopticon prison principles are being adapted to military technologies such as one of the latest American military developments, the RQ-4 Global Hawk, an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) used as a surveillance aircraft. The pilotless Global Hawk is a flying panopticon, an eye in the sky, an omnipotent all-seeing eye that works at all times of the day and night in any weather conditions, yet is designed to be invisible to enemy radars, as the need for more visibility is accompanied with a greater need for invisibility: »Just as weapons and armor developed in unison throughout history, so visibility and invisibility now began to evolve together, eventually producing invisible weapons that make things visible – radar, sonar, and the high-definition camera of spy satellites.« (Virilio) Video missiles, drones and other military surveillance technologies were developed in order to achieve real-time information on the enemy. According to Virilio these high-speed transitions obliterate real space in favor of real time; that is, the military surveillance reaches its total phase of global vision, whereby geographic distance loses weight and is compressed into instant time feeds (Live television, which is now a global surveillance apparatus in itself, works on the same principle).

[b]Total surveillance[/b]

When President Bush defended the »Patriot Act« he explained the need for wiretaps by making a comparison to police discipline: »But a roving wiretap means – it was primarily used for drug lords. A guy, a pretty intelligent drug lord would have a phone, and in the old days they could just get a tap on that phone. So guess what he’d do? He’d get him another phone, particularly with the advent of the cell phones. And so he’d start changing cell phones, which made it hard for our DEA types to listen, to run down these guys polluting our streets.« Bush’s reinforcement of the Department of Homeland Security was explained with military reasoning, to gain real-time information on the enemy: »We’ve got to coordinate between the federal government and the state government and the local government like never before. We’ve got to share information on a real-time basis.« These remarks are not just loaned metaphors from police and army discourses, but indicators of the changing character of surveillance today. Whereas the primary aim of military surveillance was to see the enemy’s deployment, and the prison panopticon was first proposed as a means to expose to the light the hidden, dark margins of society, today we are witnessing a surveillance that is directed to the center, to every citizen, each of whom is now considered a potential enemy or criminal.

This situation is depicted in »Enemy of the State« (Tony Scott, 1998), where an innocent family man (Will Smith) is increasingly caught up in a net of panopticon techniques that penetrate into every aspect of his life. He is spotted by security cameras, street CCTVs and satellites with molecular resolution that can focus from outer space on the logo of his pen; every time he uses his credit card or cell phone his location appears on the NSA’s (National Security Agency) computers. Nothing is hidden in the total surveillance society. Like the prison panopticon, which is built around the criminal as a secret structure (extracting his most hidden passions and perversions), so does the total surveillance system haunt the individual as a subject that demands the endless proliferation of inspection in order to extricate its hidden secrets. The film’s solution is the private use of surveillance techniques – a private camera that accidentally catches the murder of a politician by the NSA and helps to break their total surveillance grip. Private cams and YouTube channeling have become the new hope to reverse this situation in recent films such as »Redacted« (Brian De Palma, 2007) and »Diary of the Dead« (George A. Romero, 2007). But when the private becomes a public domain, as in »The Truman Show« (Peter Weir, 1998), this solution seems farfetched. The film depicts the life of a man (Jim Carrey) living in a reality TV show. His seemingly normal all-American neighborhood is actually a complete surveillance sphere which transmits his life to millions of people across the states. The film marks the end of the centralized surveillance gaze and its breakdown into millions of small family-unit cells, which then function as the prison’s many watchtowers. But Carrey’s situation is also potentially theirs, and ours, as everyone can watch and be watched in his little family cell. When at the end of the film Carrey tries to break out he discovers a shield at the horizon of the surveillance sphere with stairs leading up to the sky, where the producer of the show, Christof (Ed Harris), sits on his throne. The final scene depicts how Christof – a combination of prison guard, metaphysical father figure and monotheistic God who sees all, while only his voice is heard – tries to convince Carrey to stay in his cozy prison. Carrey apparently refuses and starts climbing up the stairs, but the film ends there – on the verge of a metaphysical outside, but still within the total surveillance-scape, we hear the serial, repetitive music of Philip Glass suggesting a loop of inescapable hyper-reality. Carrey’s final words are also a repetition of his character’s catch-phrase in the reality show, »Good morning, and in case I don’t see ya, good afternoon, good evening, and good night!«, which suggest that even if he eventually broke out of his TV cell, he still remains an artificial product of prime-time TV.

[b]Hot and cold media[/b]

Marshall McLuhan distinguished between »a hot medium like the movie from a cool one like TV.« Hot media emphasize one sensory organ in »high definition« (early cinema theoreticians regarded cinema as emphasizing and extending mainly eyesight) and are exclusive, that is, they control the spectator and don’t allow her/him freedom of participation (one cannot stop or rewind a movie at will but is forced to submit to its linear time course). Cold media on the other hand involve few sensory organs and are inclusive, encouraging the spectators to participate. McLuhan further argues that hot media are media of extension, which exploded throughout the world until they reached a state of reversal with the cold, postmodern technologies, which created an inward movement of implosion (from here stems McLuhan’s famous perspective of the world as a »global village«). New surveillance techniques like those of reality TV involve the public in its own surveillance, a cold surveillance that is reaching the state of implosion. This new phase is characterized by two general movements in time and space: the movement of real time becomes future time; and in space, surveillance moves from its previous structure as a center point illuminating/observing the circumference to a centerless structure where every point in itself can function as a center until the system reaches the final stage of internalization.

The movement in space is depicted in »Disturbia« (D.J. Caruso, 2007), a contemporary remake of Hitchcock’s »Rear Window« that tells the story of a teenager who spends the summer under house arrest. The house, which becomes a literal family prison cell, also functions as a panoptic center from which the bored teenager spies on his neighbors (and eventually discovers that one of them is a murderer). Every citizen is now both prisoner and prison guard, equipped with private surveillance devices such as video and cell phone cams, which allow him to become a part of the »war on crime« or the »war on terror.« The movement of time is depicted in »Minority Report« (Steven Spielberg, 2002), where the police predict future crimes and arrest people for what they are about to do. The »preventive character« of the prison panopticon has infiltrated the total surveillance society, where the knowledge obtained through real-time surveillance techniques such as the retina scan is immediately compared with an individual’s previous record, working not only to maximize and extract a person’s financial power (customized advertising) and submission (a »good subject« – i.e. not a terrorist), but also to predict future purchases or crimes. Real time has accelerated to future time. The military response time, which »was continually being cut by the technological processes of foresight and anticipation« (Virilio), has reached the private sphere, as explained by President Bush: »After 9/11, I said to the Justice Department and the FBI, your job, your primary focus now is to prevent attack. Listen, I still want you chasing down the criminals; that’s what’s expected of you. But there’s a new mind-set, and that is, because of what happened on 9/11, we’ve got to change the way we think, and therefore, your job now is to prevent attack.«

[b]The future of surveillance[/b]

The explosion of panopticon techniques across the globe has reached the verge of implosion. »A Scanner Darkly« (Richard Linklater, 2006), based on a science fiction novel by Philip K. Dick, depicts the future of surveillance at the final stage of internalization. The protagonist of the film (Keanu Reeves) is an undercover narcotics cop who is a part-time drug addict, while in his day job fighting »the war on drugs« (both the drugs and the »war on drugs,« we learn, are produced by the same corporate forces). In the line of duty he wears a »scramble suit,« a suit designed for urban surveillance and camouflage that covers his entire body and head, while projecting on its surface millions of fragmented body parts of people from all races, genders and ages. This suit is what may be called a mobile panopticon, a surveillance suit which allows him to remain invisible (he is referred to as a »constant blur«). Yet he does not necessarily see everything, as much as projecting everybody on his suit, thereby creating the appearance of complete surveillance without the actual need to keep real surveillance, just as the prison guards don’t have to occupy the panopticon’s watchtower in order to give prisoners the feeling of being observed, or as street cameras prompt us to »good behavior« without anybody necessarily being behind them.

»A new mode of obtaining power of mind over mind, in a quantity hitherto without example« (Bentham): the gaze itself is sufficient to fix us. Here again, instead of a structure of center and circumference – everybody is a potential center of surveillance (wearing his scramble suit, the protagonist is literally everybody), but with the same gesture everybody is also observed. This ongoing invasiveness of surveillance leads to the schizophrenic state where the protagonist is asked to keep surveillance on himself. This is not the situation referred to as »Big Brother« surveillance anymore. In Orwell’s »1984« the surveillance apparatuses of the state are external, and leave room for the free will of the subject to fight back, whereas in this situation the physical alignment of the panopticon is erased and internalized. The whole physical structure of the watchtower has moved inside the head: You are the prisoner of yourself.

Special thanks to Dr. Michael Wedel, Department of Media Studies, University of Amsterdam.

Bibliography:

Michel Foucault, Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison, Vintage Books, 1979

Jeremy Bentham, The Panopticon Writings, ed. Miran Bozovic, Verso, London, 1995

Paul Virilio, War and Cinema: The Logistics of Perception, Verso, London, 1989

Sun Tzu, Art of War, translated by Ralph D. Sawyer, in Military Methods of the Art of War, Barnes & Noble, 1995

George W. Bush, Information Sharing, Patriot Act Vital to Homeland Security, Remarks by the President in a conversation on the USA Patriot Act, Kleinshans Music Hall, Buffalo, New York, April 20, 2004, published on the White House website.

Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, MIT Press, 1994