Issue 1/2013 - Antihumanismus

The production line of subjectivity

On Félix Guattari’s concept of integrated world capitalism (IWC)

Félix Guattari (1930–1992) was a notorious neologiser and also liked to give a new twist to existing terms or reposition them within his own conceptual systems. It is above all the terms and figures of speech that came to light through his collaboration with Gilles Deleuze that have made it into hit lists in the world of cultural studies, the humanities and political science: schizoanalysis, becoming-minoritarian or molecular becoming, processes of de- and re-territorialisation, cartographies, rhizomatic structures, transversal machines of all kinds (and many more such expressions) have become firmly entrenched in academic discourse, at the very latest since his death i.e. since the 1990s. In contrast, the concepts Guattari worked on independently and developed further in essays and books have received scant attention, as is also true of concepts that he tied in to earlier notions and/or updated. To a large extent this also includes the ideas he shaped in conjunction with other important thinkers in the late 1970s and 1980s, for example with Suely Rolnik, Éric Alliez or Toni Negri.1

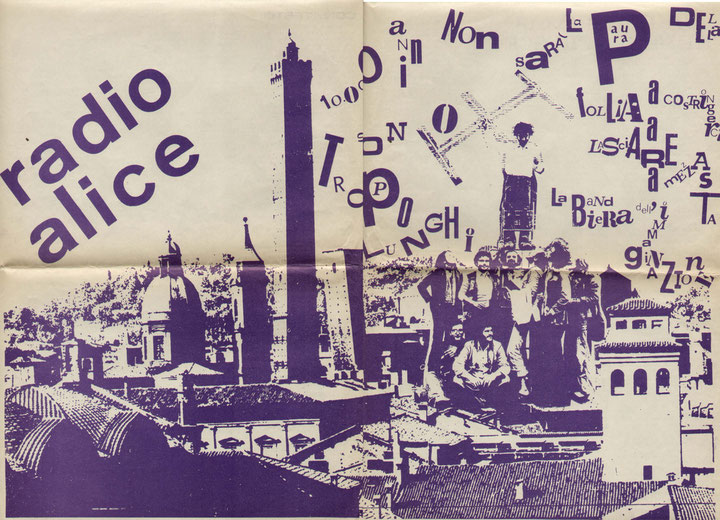

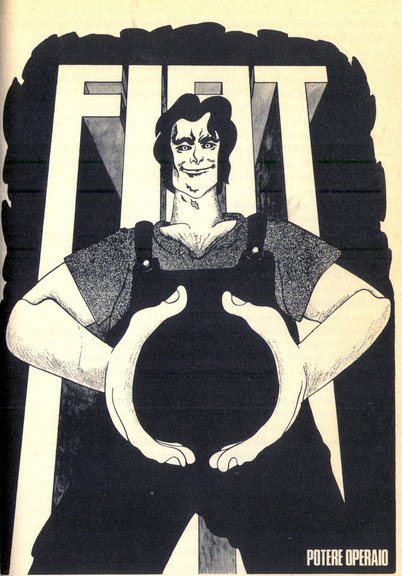

Authors that refer specifically to Guattari often share an interest in focusing not on a theoretical positioning of his concepts in the history of philosophy but instead in tracing out their roots in his activist forms of practice. This appears to make sense, particularly as Guattari’s publishing history and militant activities date back to the 1950s, when he began his anti-psychiatry and group therapy experiments at the La Borde clinic in the Loire Valley (which also to a large extent became renowned due to his involvement). In addition, he established political groups and (neo-)Marxist magazines in Paris, and, unlike many other leftist thinkers, was actively involved in the unrest around May ’68. It is important in this context to emphasise that Guattari was always primarily interested in solidarity-based (and transnational) alliances between peace movements, migrant organisations, feminist and gay/lesbian organisations, environmental activists and all kinds of representatives of the New Left. He was later involved on the periphery of the Italian Autonomia movement and protested against state repression of this movement, also cooperating with the autonomous Radio Alice in Bologna. In New York he threw himself into the identity and Communitas politics of marginalised youths and their gangs. In the early 1980s he travelled through Brazil for several months to meet with employee organisations, land occupation movements, feminists, students and various other militant groups in order to debate (and help shape) the profound changes confronting the country – poised as it was between neo-liberal structural adjustment reforms and the transition from military dictatorship to democracy. At this point Guattari was engaged in a delicate balancing act; against the backdrop of a re-ordering of the global division of labour, and the associated process whereby the East-West opposition became porous, he succeeded (together with Negri) in devising an operaist critique of changed working conditions, in particular from the perspective of the “South” (the latter in conjunction with Rolnik). In the process, Guattari’s heterogeneous international experiences and contacts generated a pioneering blend of progressive media and subject theory, a new discourse of motion and a global diagnosis of the times.

It is no exaggeration to claim that Guattari provided considerable impetus for post-Operaist and globalisation-critical discourse in many different ways. It is therefore also no surprise that concepts such as the “post-media era” ([i]Ère Post-Médiatique[/i]) or “integrated world capitalism” ([i]Capitalisme Mondial Intégré[/i]) led various authors, including Franco “Bifo” Berardi and Brian Holmes, to accord him the status of a “visionary” thinker.2 They were quite right to see him in these terms, for when Guattari died in 1992, the Internet was in its infancy, the Zapatistas were still hunkered down (or something along those lines) in the bushes and Seattle signified a revolution in the practice rooms of young guitar bands rather than the street battles of the organised anti-globalisation movement and Indymedia.

As early as 1980, in a lecture entitled [i]Le Capitalisme Mondial Intégré et la révolution moléculaire[/i], Guattari described the need for new types of networked “molecular revolutions”, calling for preparations to be made for such developments. He envisaged new forms of global alliances, underpinned by “techno-semiotic” and libidinous structures, which would pick up on traditional forms of social struggles, but would maintain autonomous structures within the struggle to attain new spheres of freedom and collective realms of action. The latter would have to be sufficiently open in order to build on TV court programmes and cartoon series in local daily newspapers in a “machinistic” vein: “We must be prepared for clashes in the most unpredictable forms, the emergence of utterly surprising personalities […], the development of still unimaginable subversive techniques, and above all come to grips with the [i]media[/i], and with informatics”.3

Tempting as it may be to engage at greater length with the anticipatory nature of some Guattarian concepts, it is just as interesting to enquire where a concept such as integrated world capitalism (IWC) actually comes from, or rather in which historical contexts it is originally positioned. In historical terms, from 1980 to 1981 the “molecular revolutions” in IWC referenced by Guattari had to pick up on the tensions between internationally networked “peaceful” resistance movements, which had grown much less comprehensively cohesive after 1968, and the militancy of 1970s pockets of armed resistance in Europe (and in the global context). Guattari’s discourse on “integrated world capitalism” and the “post-media era” coincide historically with the police shut-down of Radio Alice (1977)4 and with Lizzie Borden’s legendary feminist experimental film [i]Born in Flames[/i] (1983)5. Even before the Internet age, there were, naturally, productive overlaps between affect-economical questions and progressive media discourses, which did not entail discarding a Marxist perspective on real existing class differences and their local specificities but on the contrary emerged from attempts to update this perspective, adapt it to the complex structures of new global added-value chains and to link it to contemporary social movements discourses. As Suely Rolnik comments in the preface to [i]Molecular Revolution in Brazil[/i] (1986), Guattari had already proposed the term IWC much earlier, repeatedly proposing it from the 1960s on as an alternative to the term “globalisation”. In Guattari’s view, talk of “globalisation” conceals the most important hallmark of the worldwide expansion of capitalist markets, namely the primarily economic interest that takes precedence in the spread of capital and circulation of goods (and later in general for neoliberal economic policy). In contrast, he felt that “globalisation” was too generic a term and simply euphemistic.6

IWC

Contemporary capitalism, according to Guattari in [i]Le Capitalisme Mondial Intégré et la révolution moléculaire[/i], can be defined as integrated world capitalism for two reasons: “1. Because it constantly interacts with countries that appeared to have evaded its clutches historically – the Soviet Union, China, Third World countries. And 2. Because it tends toward a state where no human activity on the planet can escape it. […] IWC does not respect existing territorialities, nor traditional modes of life, nor the modes of social organisation of national units which today seem the most well-established. It recomposes productive and social systems on its own bases, on what I would call its own axiomatics”.

In highly simplified terms, a central trope of these axiomatics can be conceived in the following terms: alongside its territorial expansion, which generally occurs along a horizontal axis, integrated world capitalism increasingly tends to develop along a vertical axis, intervening in the most personal molecular determinations of each individual’s unconscious too: in human temporality, action and affects. Contemporary capitalism, as Guattari wrote in 1980, has already “colonised” the entire surface of the Earth and now functions like an enclosing mechanism that controls all activities on the planet. The semiotic integration of “machinistic sequences” in subjects’ actions takes hold simultaneously for both managers and family fathers, and no longer distinguishes between the world of goods and the world of affects. Small “mini-machines” of IWC are attached to our habits of seeing, hearing and feeling, as well as to our psychological faculties of reward and recognition, and “integrate”, that is to say “complete”, our production sequences and self-perception. Rather than “ideologies”, in IWC processes of “subjectification” exist, which are integral components of general production and can be calibrated and adjusted flexibly at any time. The most important aspect in this “assembly line of subjectivity”7 is that every individual believes that he or she is unique, a singular composition - an assertion that is never erroneous, but in the first instance is no reason for delight either. For this purported uniqueness is also the reason why one’s own singularity can be sold and consumed in the exchange markets of so-called social networks (analogue and digital), and also explains why fragments of this singularity can feed into other singular compositions and far-reaching machinistic contexts. When Guattari refers to processes of subjectivation, it has nothing to do with the “individual” characterised by self-will; instead Guattari does not define a person as a clear unity: the individual, the ego or its politics, and the politics of subjectivity’s individuation refer solely to formative systems of identification.8

Thinking about integrated world capitalism in terms of axioms that exert control in a totalitarian sense, rather than in terms of ideological or moral premises, is decisive in this context. Guattari describes, in rough schematic terms, three such axioms that restructure the global situation in the last quarter of the 20th century: 1. Capitalist encirclement of the entire global territory; 2. Decentralisation: the establishment of multiple centres of power and capital, which are no longer restricted to the “Western” “First World”, but may also be located in the (former) Eastern bloc, the Middle East or in the “Third World” in the “South”– a phenomenon that Guattari also calls “the end of territorialised imperialisms”;9 and finally 3. The deterritorialization of established segmentarities. For example, quantity as a factor determining the value of work is less and less significant, whilst in contrast the “intensity of machinistic sequences” integrated into production and affect relations is becoming increasingly important. The Protestant bourgeoisie for example has abandoned its progressive values and ideals; what subsists is the Protestant work ethic, which continues however to exist in a direct exchange relationship with a rigorous economy of affects: always being busy, always being successful, always being on the move, and preferably always being in a good mood. “Intensity” is also widely recognised to be the crucial performance yardstick for outsourced telephone hotline services: the despair felt by a young entrepreneur in London who phones his English service provider’s hotline service when he urgently needs to get on line in his newly renovated East End flat is now at times connected directly to the stress experienced by the hotline worker in India, toiling nonstop at a 45 cm2 workplace with unpaid toilet breaks (if any breaks are allowed at all), and working the night shift (because of the time difference between England and India). Over and above the international division of labour, a globalisation of the bodies embedded in this division of labour also occurs in IWC. In general terms, the deterritorialisation of segmentarities in IWC affects the fundamental or even superficial reshaping of work, ideology, desire, forms of stimulation, productivity etc. in equal measure. In the first instance these axioms or organisational forms concern the subject’s relationship to the global circulation of capital and to hierarchies on local markets in general terms, and in particular the question of access to information and communication apparatuses. Globalised capitalism, which “encircles itself” and “besieges itself” , reorganises itself, if need be, not only as “machinistic-semiotic integration” in love lives and in the world of work, but repeatedly in the form of excessive violence, economic crises and famines too.

In summary, this means that IWC’s axiomatics organise the machinistic integration of its subjects into the global market economy: from sweatshops in south-eastern Asia and criminalised sex-work in Sweden right through to what is dubbed the “semioticisation of capital” in mass-media and global distribution of advertising campaigns in local television and radio broadcasts and on the Internet, in profit-oriented social networks and search engines, in the creative industries worldwide and of course in the large trading centres of the financial world, São Paolo, Hong Kong, New York, Frankfurt etc. “As a function of the country or of social stratification”, Guattari writes, “the modalities with which integrated world capitalism becomes established as a twofold form of repression vary”. These include direct repression through material constraints, external economic and social control, the production of goods, social relationships and their meanings, as well as the linkage to a machinistic assemblage on a global scale, producing subjectivity, which “has become the fundamental element for the formation of the collective workforce and collective social control”. 10

One step back, two steps forward

In the early days of his career, it was also important for Guattari – as a pupil – to establish critical distance vis-à-vis his teacher, the French super-Father of psychoanalysis, Jacques Lacan; and, in conjunction with this, to establish critical distance – as a public intellectual – in respect of Lacan’s influence on certain Structuralist interpretations of Marxism, for example in the Althusserian vein. It is however essential to understand that Guattari did not reject either Lacan’s linguistic-Structuralist turn in psychoanalysis or Althusser’s ideology critique and theoretical anti-humanism entirely, even later, for example in the context of IWC. It was rather that he inverted, extended and implicitly utilized their Structuralist approaches. In this sense, Louis Althusser’s concept of protomachinistic over-determination (in the sense of his Marxist-Leninist reading of Freud) should be considered not as a solely “historical” determination of revolutionary subjects (in the sense of classical historical materialism) but instead as an important predecessor of Guattari’s own “machine” concepts and his later “molecular revolution”. In this respect, Guattari insists vehemently on the task of a subject conceived as autonomous, demarcated from the exterior by a casing of skin and hairs, precisely because IWC’s machinistic production contexts and control mechanism anyway penetrate, traverse, fragment and exploit us the whole time.

By way of conclusion, it is also interesting to note that a comparatively unwieldy term such as integrated world capitalism can be understood all the more precisely when distinguished clearly from other contemporary concepts. Whilst for Foucault – to remain with the idea of being penetrated by the vectors of capitalism – the focus was on exploring the “internalisation” of power relations in bodies and in the mind, Guattari’s idea of an “integration” of world capitalism insists that theoretical analyses must always include the subject as the “command button” of globally circulating flows and fluctuations. It is not the subject, but world capitalism that is integrated in IWC ([i]integrare[/i], Latin: re-establishment of unity). This can be illustrated in simplified form in the following terms with reference to subversive practices: in the light of Foucault’s concept of subversive technologies of the self, the issue is not so much [i]that[/i] one eats a banana, but rather [i]how[/i] one eats a banana. In contrast, in Guattari’s molecular revolution, the subversive libidinous potential of eating a banana is directly linked to the IWC’s interests in the self-styled development sector - or rather, in the reshaping of the Caribbean economic area - and to the “Western”, ideologically determined desire for exotic fruits as an internalised illusion of freedom. The molecular-machinistic subversion in IWC can function only if the orality of banana eating is coupled to Puerto Rican plantation workers’ sweat and struggle for emancipation, for otherwise the boundaries of individually controlled spaces of freedom remain inviolate, and the molecular revolution remains mere idealism. In a nutshell: just like Althusser, Foucault, for all his anti-humanist reputation, tends to maintain an anthropocentric and Eurocentric focus, whilst Guattari always explicitly addresses the dismantling of Euro- or ethnocentric approaches. In the process, Guattari combines contemporary discourses on labour and affect relations with other theorems that have also engaged historically with affect structures’ capitalisation and with forms of circulation, global supply and demand that pick up on this idea, for example in the work of Fernand Braudel and the Annales School (already quoted extensively by Guattari in the works he co-authored with Deleuze); or, in a limited sense, Immanuel Wallerstein’s world system theory.

If nothing else, the protest forms that have emerged recently and their parasitic besiegement of real and virtual spaces (in profit-oriented social networks on the Internet and in the public squares of economic metropolises) make clear that Guattari’s concept of integrated world capitalism, whilst not couched in particularly chic terms, can certainly prove usefully, specifically in devising a new theoretical approach against the backdrop of the current economic crisis and the international alliances and enforced conformity of protests, trade union federations and all types of social movements.

Translated by Helen Ferguson

1 The “attention” that the individual terms have received fluctuates from language to language and depends in each linguistic area on the availability of the various texts. In the German-speaking world in particular there is a dearth of translations, for example of Suely Rolnik’s book [/i]Micropolítica. Cartografias do desejo[/i] (1986; the 11th edition of the original Portuguese version was published in 2011; the book is viewed as a classic throughout Latin America in the context of social movements); or [/i]Les nouveaux espaces de liberté[/i], co-written with Antonio Negri (1985, original in French, not translated into German; the first English translation in 1990 was published under the title [/i]Communists Like Us[/i], and later appeared as [/i]New Lines Of Alliance, New Spaces Of Liberty[/i]. Above all one term that plays a prominent role in Guattari and Deleuze’s thinking has only recently become a real hit in numerous translations thanks to Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt, namely the multitude.

2 C.f. e.g. Franco Berardi (Bifo), [/i]Félix Guattari. Thought, Friendship and Visionary Cartography[/i], Basingstoke: Palgrave McMillan, 2008, here above all Chapter 3, [/i]Integrated World Capitalism [/i]; und Brian Holmes, [/i]Guattari’s Schizoanalytic Cartographies[/i]; http://brianholmes.wordpress.com/2009/02/27/guattaris-schizoanalytic-cartographies/#sdfootnote14sym (accessed December 2012). In conjunction with Karel Clapshow, Holmes was also responsible for the English translation of Guattari and Rolnik’s [/i]Micropolíticas. Cartografias do desejo[/i], published in 2008 as [/i]Molecular Revolution in Brazil[/i] by Semiotext(e)/MIT Press, Los Angeles/Cambridge, Mass.

3 Guattari’s [/i]Le Capitalisme Mondial Intégré et la révolution moléculaire[/i] is based on an unpublished text of a lecture in French from 1980. Suely Rolnik first published this in 1981 in Portuguese as [/i]O Capitalismo Mundial Integrado e a Revolução Molecular[/i], in S. Rolnik (ed.) [/i]Revolução Molecular: Pulsações políticas do desejo[/i], São Paolo: Brasiliense, 1981. The quotations used here, if not otherwise indicated, are based on the translations from German from Spanish by the author of this article. [/i]C.f.El capitalismo mundial integrado y la revolución molecular[/i], in F. Guattari, [/i]Plan sobre el planeta. Capitalismo mundial integrado y revoluciones moleculares [/i], Madrid: Traficantes de Sueños, 2004, pp. 57–74. Interestingly, the text first appeared in Spanish in 1992 in the very first edition of the Mexican journal Archipiélago, published by students at UNAM (Autonomous University of Mexico) in Mexico City, the same university at which it is rumoured that the Zapatista leader, Subcomandante Marcos, studied. The Zapatistas’ aggressive use of new media technologies right from the start of their insurgency in 1994 marked a new paradigm for social movements’ public relations policy worldwide. It seems reasonable to assume that a number of the students who ultimately joined the EZLN’s armed struggle read the journal [/i]Archipiélago[/i] regularly at university. Political reading groups were an integral component of the movement during its initial founding phase.

4 Using the pretext of the struggle against left-wing terrorism, for example against the notorious Brigate Rosse, the Italian state neutralised numerous peaceful opposition organisations and intellectuals. Negri for example was imprisoned for several years, and the radio station Alice was closed down.

5 [/i]Born in Flames[/i] (Director: Lizzie Borden, shot between 1979 and 1983) follows the fate of two competing feminist pirate radios discussing the question of the form a socialist revolution should take from a sexually liberated feminist point of view, and in the process presents a clash between a white lesbian perspective and an Afro-American working-class perspective on the topics of equality, work, communication and sexuality. The whole debate unfolds in a futuristic New York and is conceived as a discursive corrective to the socialist world revolution which in the film had occurred many years earlier.

6 C.f. Guattari/Rolnik, [/i]Molecular Revolution in Brazil[/i], p. 10 (footnote 2) and p. 477.

7 Guattari writes: “The assembly line of subjectivity: Rather than speak of [/i]ideology[/i], I always prefer to speak of [/i]subjectivation[/i], or the production of [/i]subjectivity[/i].” (Ibid., p. 35.)

8 Ibid., p. 53, German text paraphrased from the English version by M. J. H.

9 For Guattari the systemic bureaucracy of the Eastern bloc countries, which de facto still existed in1980, along with the simultaneous opening-up of markets was not in contradiction to the control mechanisms of integrated world capitalism, just as he held that the glaring social imbalances in countries in the southern hemisphere were also not in contradiction to these mechanisms. This is an interesting realization, particularly as in 1980 the yet-to-come fall of the Iron Curtain was not really part of public consciousness. The economic boom of the BRIC states also still seemed inconceivable, at least for European public opinion. Viewed soberly however we must assume that Guattari’s “empirical” experiences during his lengthy travels through Brazil’s industrial centres and rural expanses contributed at least as much to the pioneering nature of his writings as his much-invoked visionary spirit.

10 C.f. Guattari/Rolnik, [/i]Molecular Revolution in Brazil[/i], p. 53, German text paraphrased from the English version by M. J. H.