Issue 1/2015 - Net section

Non-human Eyes Are Watching

The spread of the computerised gaze from above

25 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, a mise-en-scène of its trajectory was recently created in the form of a “light border” between former East and West Berlin. The whole project design was couched in terms of a camera looking down from above. For the CGI visualisation, it is immaterial whether any lens could actually identify the illuminated balloons through the November cloud cover. In Hong Kong, drones helped document protests. Students in white T-Shirts wave at the drone camera from the elevated highway in the central business district.1 In Kiev, men in camouflage gear collect money to fund drones for their privately organized battalion at an exhibition opening. A user shares information on Facebook about a German newspaper that repeatedly offers a drone as a gift for subscribers, emphasising that it makes him wince each time he sees the ad. Paul Virilio talks about “militarisation of information”; the vertical perspective makes inroads into the media and everyday experience.

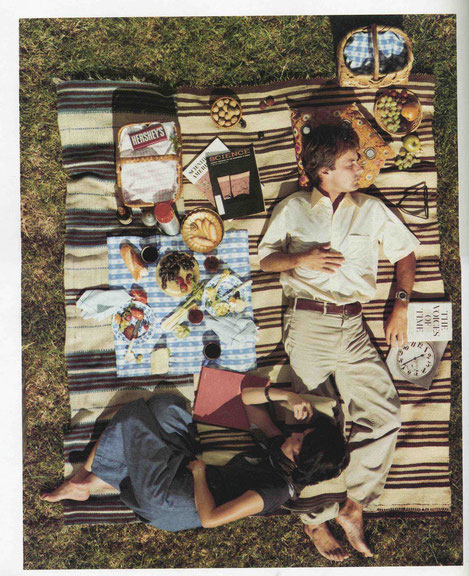

When Charles and Ray Eames produced their nine-minute film Powers of Ten2, the Apollo missions had been completed and most Americans had already seen the famous Blue Marble image depicting the Earth as an object. The architect duo filmed a tracking shot that begins on a picnic blanket in Chicago, heads up into the Milky Way and then descends again to the body of the man relaxing on that self-same picnic blanket. This “hand-made” film is composed of photographs of photographs, composite maps, photos of maps and drawings, and photographs of paintings, which were in turn created from microscope images – well-choreographed material that produces an imagined sequence rather than an indexical trace.3

What does Powers of Ten evoke today? Space was the “new frontier” of the 20th century, but nowadays no-one still believes in creatures on other planets. Paul Virilio: “The threat, and the great confinement, is that now we have only having the concept of a reduced Earth. An Earth constantly flown over, journeyed across, its natural scale violated.”4. The issue at stake is thus the gaze directed down to Earth. Media representations and technologies play an important role in our localization in horizontally configured screens and networks whose visual economies demand visibility; just think for example of Face Time, retina displays, facial recognition software or apps such as Vine and Snapchat. Yet the vertical dimension appears to offer scope to step “outside”, to back away from digital networks and create an “objective” state of non-embeddedness.

It is quite conceivable that this wish also resonates in the film Gravity (Alfonso Cuarón, 2013), which celebrates the magnificence of space in IMAX format, with a tangibly more nostalgic narrative undertone: nostalgia for the universe as it was once depicted in films and magazines, or in Blue Marble, when that photo was still new. Gravity looks back in this vein to what is now an old frontier, considering the universe as a military sphere of influence and the arena of the Cold War arena, concerns with renewed topicality in the light of drone technology. Hollywood romanticized this past in images of the first moon landing, the Apollo missions or Voyager spacecraft. During his term in office, John F. Kennedy launched a government programme by the name of New Frontier, which was intended – as he poetically put it – to allow Americans to reach the stars in the new Space Age.

Can pop culture references, such as those found in Gravity too, serve to conceal current geopolitical interests? In the wake of privatisation of the satellite market in the 1990s, space has recently experienced a new impetus as a territory and a camera perspective – to a large extent thanks to drone technology. Furthermore, firms like Google are beginning to take an interest in this realm as a screen for projecting symbolic power and/or as an extra-terrestrial data source. Space has therefore once again assumed new significance from a cultural, economic and political perspective, with narratives and icons established in the 20th century still serving as central points of reference. Since 2007 Google has invested in in aerospatial symbolism, as the Google Lunar XPRIZE competition (Moon 2.0) reveals. What is the intention here? To a large extent, the focus is on a further opportunity to collect data: privately funded teams aim to send a robotic spacecraft to the moon by December 2015, and to transmit the images and data it collects.

While users thus predominantly remain horizontally embedded in the matrix (with the outside world seeming to vanish), states and companies have access to a transcendent “wider context” – vertically, so to speak – that is increasingly read and evaluated by computers. If Charles and Ray Eames were to shoot their film again today, would they try to obtain video material from drones? Material that does not necessarily have positive connotations? When they produced Powers of Ten, satellite images were not available for download. Which images are subject to the same kind of control today? What kind of pictorial material would calculations run on quantum computers, for example, be able to convey?

In The Conquest of Space and the Stature of Man, Hannah Arendt adopts an intriguing way of looking at data. She writes that data are not “phenomena, appearances, strictly speaking, for we meet them nowhere, neither in our everyday world nor in the laboratory; we know of their presence only because they affect our measuring instruments in certain ways”.5 Picking up on Heisenberg’s theories, Arendt argues that there will no longer be any need for new technology when technical progress ceases to be explicable to our sensory world. Drone technology has reached something like that point today.

The vertical perspective can currently be found in projects such as Google Earth, whose inventors state that they were inspired by Powers of Ten, as well as in large-scale sponsoring events like the stratospheric skydive by extreme sportsman Felix Baumgartner, who shot spinning back down to Earth in just a few minutes. As Baumgartner’s cam-video shows, the vertical perspective emerges as a highly stressful first-person view, which lacks the simulated machine elegance and calm that distinguishes Powers of Ten. Baumgartner’s video is a dizzying nosedive down to Earth, contrasting with the smooth, realistic movements that run through the various image sequences in Powers of Ten, in which aerial and satellite shots are arranged frame by frame.

Whereas Charles and Ray Eames sought to acquaint their audience with new computer technology, Google Earth can be viewed as a tool that accustoms users to the role of active observers from on high, and/or to being under surveillance themselves. However, it does not give users access to the actual technology. In Hannah Arendt’s view, it is fatal if science does not communicate with our sense-based world, and lacks generally comprehensible vocabulary to convey its research intentions. Watching Powers of Ten, we can read from it a desire to leave behind the “networked state”– to be somewhere else for a short moment, either in a macro- or a microcosm, although both, ironically, look extremely similar.

Translated by Helen Ferguson

1 Drone shows thousands filling Hong Kong streets, 29th September 2014, Facebook/Nero Chan; www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q919bQOThvM#t=59.

2 Powers of Ten: A Film Dealing with the Relative Size of Things in the Universe and the Effect of Adding Another Zero dates from 1977, which was also the year in which Walter de Maria made his Vertical Earth Kilometer at documenta 6 in Kassel. Was there perhaps something in the air in 1977 that incited vertical modes of thought?

3 C.f. Janet Harbord, “Ex-centric Cinema: Machinic Vision in the Powers of Ten and Electronic Cartography”, in: Body & Society, 2012, p. 107.

4 Paul Virilio, Cyberwelt. Die wissentlich schlimmste Politik. Berlin 2011, p. 49.

5 Hannah Arendt, “The Conquest of Space and the Stature of Man” (1963), in: The New Atlantis, Autumn 2007, p. 43–55.