Putting the focus on the manifold forms of appropriation of a shared resource opens up a horizon on artistic practice beyond functionalization and heteronomy, which so often characterize the practice of participatory projects.

Since the 1960s, when the cultural order of modernity – McLuhan’s “Gutenberg Galaxy” – began to slip, the concept of “participation” has played an important role in expanding the practices of art and redefining the roles and relationships of artists and audiences. Fluxus artists opened up the execution of the artwork with the help of instructions for action (“scores”), socially and politically oriented “post-studio” practices involved the audience or other non-artistic actors in the production of artistic “situations”, interactive art made the active participation of the viewer a condition of reception. Under the banner of “relational art”, participation, reduced to an unspecific shared “time to be lived through”, became the actual focus of artistic action.

This development was neither accidental nor isolated, but embedded in major social changes. On the one hand, the emergence of a media infrastructure, that focused on mass self-communication and favored modes of subjectivation beyond the silent recipient. On the other hand, the rise of the communicative and informational dimensions of work and the associated increasing valorization of social and cultural everyday activities that had previously been far removed from the market.

Critique of participation

Along with the utopias and disillusionments that accompanied these processes over the last 50 years, the idea of participation in art also underwent a revaluation. While at the beginning, and to some extent still today, it was used for the breaking up of traditional cultural configurations and power relations, participation was also taken into service by new, flexible relations of exploitation and power. At the latest, the empty idea of participation in Nicolas Bourriaud’s approach to “relational aesthetics” (1998) sparked a fundamental critique of the idea of participation as an artistic strategy. For example, Claire Bishop (2012) emphasized the compatibility of participatory approaches with neo-liberal forms of control through activation and the if not direct economization, then al least functionalization of art in line with the changing agendas of exhibition venues and funding institutions. On the recipient side, Bishop noted that the willingness to participate testifies to a problematic tendency toward “voluntary subordination to the artists’ will, and of the commodification of human bodies in a service economy.” The mode of subordination comes from the fact that it is usually the artist who determines the conditions of participation in advance, and confronts the counterpart with an already predetermined situation, leaving him/her only the possibility of either complying with the conditions set or of refusing to participate. This is not real freedom. For what at first glance looks like a relinquishment of power – after all, certain elements are left to third parties – turns out, on closer inspection, to be the exercise of another form of power: to define the conditions of interaction, the social and technical protocols, and thus to align them from the outset with one’s own interests, without ever having to tell the participants what they have to do. Commodification comes from the fact that unpaid voluntary activities are also a form of work whose added value can be organized elsewhere. The social mass media have institutionalized these two principles very successfully, with all the problems that we can clearly see today.

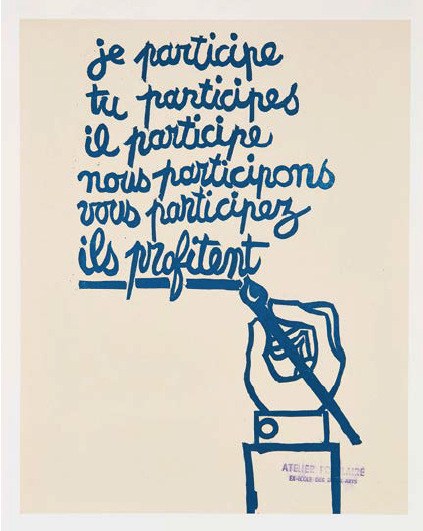

Atelier populaire, numéro 3, 1968

Against this use of art by curators and funding agencies, Bishop calls for a renewed autonomy of art, which as a symbolic activity should always be a step away from society. However, she remains vague as to what such an autonomy of artistic action might look like. Many interpret this as a return to a rather conventional conception of artists and artwork, perhaps also because it fits very well into the conservative zeitgeist.

The horizon of appropriation

However, this does not have to be the only conclusion that can be drawn from the not unwarranted criticism of participation. A number of ambitious artistic projects examined by the Creating Commons research project are also abandoning the idea of participation. They focus on the idea of the “free resource” and the practice of appropriation, either explicitly or implicitly. Whereby here it is not the appropriation by a privileged artist subject that is central as in the classical “appropriation art”, but the process of appropriation itself is opened.

Kenneth Goldsmith, who has been running UbuWeb, an online archive of the audiovisual “avant-garde”, since 1997, does not offer any possibilities for the users of the archive to contribute themselves. He alone makes all the decisions from the technical to the curatorial, as he explained in an interview with Cornelia Sollfrank (2013). Here, the “wisdom of the crowds” is not the focus, nor is a multi-perspective selection to be made. No, in the age of exuberant chaos, Goldsmith stresses, it is the artist’s task to go in and create order, that is, to develop a context in which things are put back into a specific context of meaning. At the same time, however, it is not simply a definitive, timeless selection based on the authority of the expert, but a highly situated one. Goldsmith never tires of emphasizing that as an artist he is actually the wrong person to operate an art-historical archive and that strictly speaking it is not an archive at all (with the claim to long-term preservation). Rather, this “personal project” could be over from one day to the next and UbuWeb could disappear from the net again, for whatever reason. The suggestion is that everyone should download what is important to them personally to protect their own choices from disappearing. To make this practicable, a download link is added to each work. However, the possibility of downloading is not only relevant because of the ephemeral structure of the archive, but because it allows anyone to step out of the role of the recipient and transfer the work into a completely different context of use.

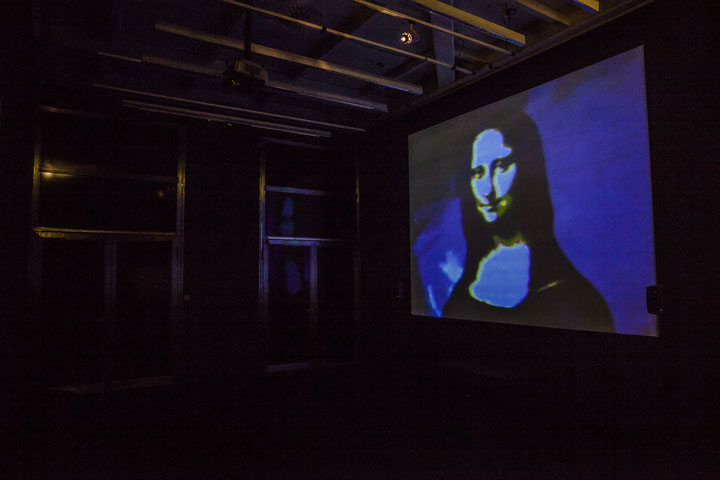

Ubu in Athen, TOP TENS Ausstellungsansichten, Onassis Cultural Center

Copyright: Andreas Simopoulos for Onassis Stegi

In fact, in order to use UbuWeb one neither has to share Goldsmith’s theory of uncreativity (2011) as context displacement nor in any other way subscribe to the framework he sets. One can also simply appropriate the resource(s) and do whatever one wants with it, in one’s own context. Nevertheless, UbuWeb is not only a functional platform, a normal file hoster, but symbolically as well as practically an investigation of what artistic practice can mean today, under the conditions of a chaotic, exuberant and commercialized information sphere. Accordingly, the figure of the artist does not disappear. On the contrary, Goldsmith himself has meanwhile become a star, teaching at elite universities and being invited to the White House. But he, and this is new, no longer alone defines the framework within which a user can move.

The idea of free resources plays a central role in this shift. It provides the common ground from which anyone can create their own highly context-specific realities. It is, therefore, a question of a new articulation of the relationship between the singular and the collective. While many participatory projects are based on the utopia of the (temporary) community, the role of the artist as the author of this one community remains untouched. Accordingly, the added value of participation usually does not accumulate with the participants, but with the artists. The possibilities of appropriation create a different relationship. The role of the artist as the author of the resource remains strong, but the users have the possibility to transfer it into their own context, which can exist with or without a reference to the “source”, or to function as the author themselves and thus clearly gain freedom of action.

Basically, the practice of appropriation could be described as a kind of “personalization”. Things are brought into a form in which they correspond to the situatedness of the user. In contrast to personalization as practiced by the “social mass media”, control over this process does not lie with the central provider but with the periphery, with each individual. Even if this does not automatically eliminate the problems of subjugation and value creation so clearly visible in participatory projects today, the shift towards appropriation creates a new dimension of freedom whose possibilities are neither artistically nor politically exhausted.

References

- Bishop, Claire, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. London: Verso 2012.

- Bourriaud, Nicolas, Esthétique relationnelle. Dijon: Les Presses du reel 1998.

- Creating Commons; http://creatingcommons.zhdk.ch/.

- Goldsmith, Kenneth, Uncreative Writing. Managing Language in the Digital Age. New York: - Columbia University Press 2011; https://monoskop.org/media/text/goldsmith_2011_uncreative_writing/.

- Sollfrank, Cornelia, The Poetry of Archiving, Interview with Kenneth Goldsmith, 2013; http://creatingcommons.zhdk.ch/?p=365.