Issue 4/2019 - Net section

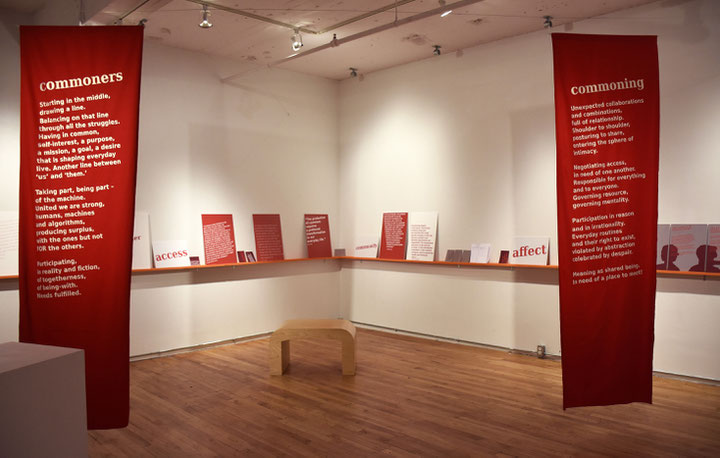

What Can We Learn from the Commons? Aesthetic Practices of Learning and Unlearning

Educational formats and projects in the art field have become part of everyday practice – at least since the “educational turn”1. Art institutions offer workshops or provide resources for diverse formats: Colleges, academies, free schools.2 In this way, they create learning situations in which speculation, reflection, updating, and production can take place – independent of prescribed necessities and according to self-determined exigencies. Extensively theorized and problematized as part of curatorial practice, these activities stand for a “shift from exhibition-making to the production of knowledge”3 and have snatched the formerly rather neglected questions of education as a (partial) task of art from the realm of classical mediation and endowed them with the symbolic power of new discursive power. Art mediation reacted to this with its own shift, an “educational turn in education”4 that consists of adopting and further developing increasingly radical and critical approaches to education – and shaping them into a critical practice of mediation.

Questions that accompany these developments both in the curatorial field and in the field of mediation are questions about one’s own relationship to the institution for which one works or within which one works. It is not uncommon for direct relations with institutional power to produce contradictions with one’s declared critical practice – and such contradictions cannot always be made positive or productive through reflection alone. This may be one of the reasons why artists* and cultural producers* are working to create their own places and spaces for dealing with knowledge. The creation of self-determined situations for learning – and unlearning – promises to escape institutionally established boundaries and thus not only to be able to act more freely in terms of content but also to test new methods of producing and imparting knowledge in practice by fundamentally questioning traditional knowledge practices.

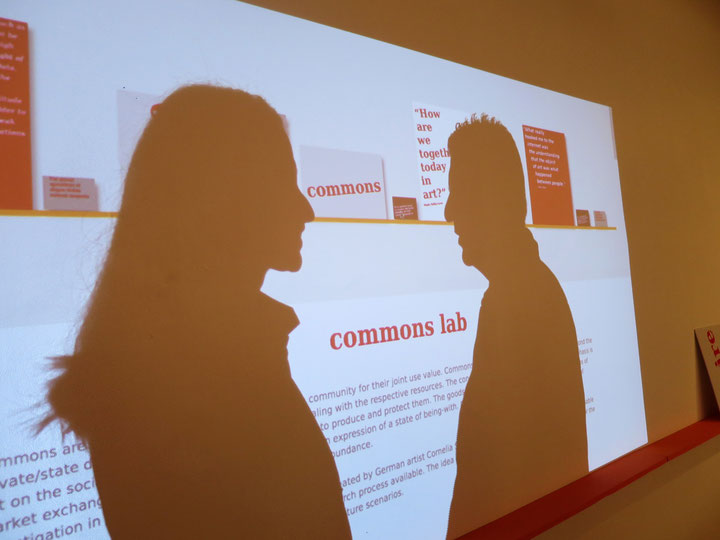

Taking our work in the research project Creating Commons, in which aesthetic practices committed to the production or preservation of digital commons are investigated, 5 as a starting point, I would like to reflect here on a few selected projects in which educational aspects also play an important role. These are different formats, most of which are located outside of traditional institutions. In these projects, what Philip Agre has called “Critical Technical Practice”6 is intertwined with self-organization in an expanded artistic environment using emancipatory pedagogical approaches.

The Public School

Meanwhile, The Public School has become a classic.7 Founded in 2008 in L.A. by the US-American artist Sean Dockray, it evolved from reading together in Reading Groups, with the self-organized art space in which these groups met also being an important element. It is a school without a curriculum, composed of a group of interested people, a space where they can meet, and a website where the seminars are coordinated. The principle is that individuals offer what they can teach or what they would like to work for, and others make specific wishes. This means that the contents of the seminars are not curated, but develop exclusively according to the needs and competencies of the participants. The process of negotiation takes place online on the project’s website, which not only allows all decision-making to be followed transparently but is also open to all interested parties. This makes it the organizational heart of the project. For the programmers* of the website, the political claim of the project is most strongly reflected in the software: “Every programming decision influences what the users* see and how they can act.”8 In order to realize the claim of greatest possible inclusiveness, the website is continually adapted and further developed in consultation with its users*. This means that the tool that enables new knowledge-production situations is itself part of the “commoning” process. Not only do form and content meet to open up a new space of possibilities; digitally networked infrastructure also meets with a local community. Due to its universal structure, the project was able to spread to about a dozen other cities.

Mz* Baltazar’s Lab

One project that, in contrast to AAAARG, for example, is gaining considerable momentum through its local positioning and the formation of a community is the Vienna-based Mz* Baltazar’s Lab9 – a hacklab, in existence since 2008, which is run by a trans*feminist collective. The core of this project is the space in which workshops, meetings, lectures, and exhibitions take place. According to Stefanie Wuschitz, one of the co-founders, the physical space as a common resource represents an important moment to bring together diverse users* and to create collective practices.10 Collectivity means common knowledge production, but also care and solidarity.11 The ethnologist Sophie Toupin locates Mz* Baltazar’s Lab in the worldwide scene of feminist hackspaces, which by creating their own spaces promote feminist resistance practices and expand the conventional understanding of hacking with gender-related and feminist aspects.12 Intersectionality is another important working principle, and the associated preoccupation with inequality, oppression, and violence brings entirely new dynamics to the strongly masculine and white field of technology. Accordingly, the activities of the hackspace develop along the principles of feminist hacking,13 whose basic assumption is that both technology and gender are coded and thus also codable – i.e., changeable – systems. Feminist hackspaces are places where a coexistence is cultivated that clearly differs from the traditional hacker scene and its merciless meritocracy, so that as many people as possible can train themselves in an emancipatory engagement with technology.

École de recherche graphique (e.r.g.)

The projects mentioned above could be supplemented by a number of other examples since almost all of the projects examined by Creating Commons also have educational aspects. These range from workshops within the framework of public institutions14 to the creation of one’s own infrastructure15 and self-organized schools.16 The example of the École de recherche graphique (e.r.g.) in Brussels shows how a radically critical pedagogical approach within an institution can sound out and even expand its boundaries. The publicly funded school, which follows the tradition of experimental universities of the 1970s, has been undergoing an institutional transformation since 2016 under its current director Laurence Rassel. The principles of free software are combined in Rassel’s management concept with feminism and the “institutional psychotherapy” developed in France in connection with reform psychiatry.17 For Rassel, the focus here is on setting in motion what is stuck in an institution – the instituted – through a process of re-establishment.18 Here, the central concern is not the construction of non-institutional contexts, but the transformation of an existing structure with the aim of involving all participants in the process of transformation and thus practicing a form of collectivization.

Educational Commoning

For all educational approaches in the field of digital commons, the principles of free software are an essential inspiration.19 They not only configure the collaborative and open-source creation of software but also stand in their social dimension for a reorientation of power relations in relation to the creation, dissemination, and authorization of knowledge in the age of the Internet. With values such as collectivity, transparency, new forms of self-organization and radical free access20, they provide essential impulses for emancipatory knowledge practice in general.

However, these values are not simply present, but are the subject of an ongoing process of negotiation, reflection, and development, i.e., “commoning.” Educational formats in this context are nothing other than the creation of situations in which this process can take place. Not only is given knowledge imparted, but it is also shown how knowledge is recognized and legitimized and how a diverse set of knowledge can be created or disseminated. Joint learning – and unlearning – is thus one of the essential resources of digital commons.

[1] See Irit Rogoff, “Turning,” in Curating and the Educational Turn, Paul O’Neill & Mick Wilson (Eds.) (Amsterdam: Open Editions, de Appel, 2010).

[2] Some examples: Community College, Nachbarschaftsakademie, metroZones Schule für städtisches Handeln, A.C.A.D.E.M.Y, Free University, etc.

[3] Jaschke and Sternfeld, p. 14.

[4] Ibid., p. 17.

[5] https://www.zhdk.ch/forschungsprojekt/544343.

[6] Philip Agre, “Toward a Critical Technical Practice: Lessons Learned in Trying to Reform AI,” in Social Science, Technical Systems, and Cooperative Work: Beyond the Great Divide, ed. Geoffrey Bowker et al. (London: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1997).

[7] http://thepublicschool.org. The technical infrastructure is presently being restructured and reprogramed.

[8] An interview with Sean Dockray, Expanded Appropriation, https://vimeo.com/60889535

[9] http://www.mzbaltazarslaboratory.org/

[10] Feminist Hackspace, Interview with Patricia Reis and Stefanie Wuschitz (2018), https://vimeo.com/319823285

[11] See also spideralex, “Creating New Worlds – with cyberfeminist Ideas and Practices,” in The beautiful warriors: Technofeminist Praxis in the 21st Century, ed. Cornelia Sollfrank (minor compositions, 2019).

[12] See Sophie Toupin, “Hackerspaces: The Synthesis of Feminist and HackerCultures,” Journal of Peer Production 5 (2014).

[13] See Sophie Toupin, “Feminist Hacking: Resistance through Spaciality,” in The beautiful warriors, ed. Sollfrank.

[14] For instance, Public Library, an exhibition at the Württembergischen Kunstverein in Stuttgart (2014): https://www.wkv-stuttgart.de/en/program/2014/events/public-library/.

[15] For example, Furtherfield, http://www.furtherfield.org/.

[16] Relearn: Variable Summerschool: http://constantvzw.org/site/Relearn-Variable-Summerschool.html

[17] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Institutional_psychotherapy

[18] See Gerald Raunig, Instituent Practices. Fleeing, Instituting, Transforming (Vienna: transversal texts, 2006): http://eipcp.net/transversal/0106/raunig/en.html

[19] See Free Software Foundation Europe: https://fsfe.org/about/basics/freesoftware.de.html and Christopher Kelty, Two Bits: The Cultural Significance of Free Software (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008).

[20] See the Guerilla Open Access Manifesto by Aaron Swartz: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guerilla_Open_Access_Manifest.