Most of the pressing and recurring issues discussed in the field of arts today are closely related to the urge to downscale, to degrow, to let go of the imaginary of progress. Calls for social and climate justice, for a decolonization of culture, for an opposition to established forms of patriarchy aim for the acknowledgement of multiple worlds, of their needs and potentialities. Exhibitions, festivals, biennials, artworks and publications address the need for forms of resistance against forms of exploitation and extractivism. This discourse and context also refer to shifts needed within the art world itself with regard to cultural representation and inclusion but also to events’ scale, budget and footprint. Can the art world itself, though, with its institutions and people really aim to degrow and stand as a paradigm for the societal, political and environmental changes needed? What does it mean to apply a logic of downscaling to the arts? Which limitations are to be taken in mind and where do possible contradictions lie?

Degrowth is not a new idea or concept. When the term first appeared in the early 70s, it was the period of the rise of the environmental movement. André Gorz used the word “décroissance,” to stress the incompatibility of capitalist ‘growth’ with planet’s scarce resources and to underline that unavoidably “human activity finds in the natural worlds its external limits”.1 Gorz clarified at the same time that the problem lies most of all in the mentality, the way of thinking of contemporary life:“It is not so much growth that must be attacked as the illusion which it sustains, the dynamic of ever-growing and ever-frustrated needs on which is based, and the competition which it institutionalizes by inciting each individual to seek to rise above all others.”2

This illusion about growth and progress, as other scholars clarify, is a construct of the West, of the Global North directly connected to the exploitation of the South.3 Degrowth is specifically about letting go of this imaginary and demanding change based on individual and political action. It is about respecting the limits of the planet while realizing and acknowledging mutual dependencies on a social and ecological level. At the core of it, lies the idea that all lives need to be equally respected with their needs considered and fulfilled. Practices of degrowth are based on the principles of conviviality and co-existence.4 To succeed a transition towards a more sustainable world though, the common western understanding of “time, gender, death, and democracy” need to change.5 One needs to leave behind the idealization of optimization and productivity based on an antagonism for superiority and dominance over other individuals, sexes, peoples, species. The prefix de- describes exactly this need to actively change an existing situation, to un-do and un-make a condition understood as given based on linear progress.

Degrowth is a recurring proposal, a critique, an idea, a slogan, a movement. It has especially been discussed in relation to the financial crisis as well as in relation to depletion, waste and the planetary emergency. The recent pandemic brought the discussion on degrowth again to the foreground. The first lockdown seemed like a period of an attempt to slow down human activity in order to save lives and not the economy, while also allowing the more-than-human world to breathe. Soon, though, it was proved that this was only a pause with the aim to return to the ‘normality’ of productivity and progress the soonest possible. The economic sector had to make up for the lost time, accelerating as much as possible in order to avoid a worse economic crisis emerging. The chance, though, might have not been entirely missed. Liegey and Nelson argue that “degrowth invites us to systematically analyze each of the crises we face”6, becoming a tool and an answer, while Matthias Schmelzer, Andrea Vetter and Aaron Vansintjan emphasize that degrowth constitutes not only a critique but also a proposal and a vision for a better future.7

A number of art exhibitions and events organized in the last decade addressed the potential and challenges of degrowth. Among them was the show On the Metaphor of Growth (2011)8 hosted at Kunstverein Hannover, Frankfurt Kunstverein and Kunsthaus Baselland with exhibits divided at the different venues raising questions about how and why growth is understood as desirable and natural. The Plus de Croissance. Un capitalisme idéal... (2012)9 Noisiel's Ferme du Buisson in France followed, focusing on the ambivalence of the myth of growth in times of financial crisis addressing its potential but also its limits. Slow Future at Castello Ujazdowski in Warsaw in 2014 underlined the necessity of exiting the myth. As Serena De Dominicis notes having studied the specific aforementioned shows, even from the order of the titles one can realize how the critique on growth was strengthened.10 To an extent and at that moment, the imaginary of endless growth was collapsing in the discourse of the arts, but the question that was open was how institutions themselves were changing while supporting this shift of perception.

The public program The poetics of degrowth. How to live better with less? of the XII Biennial of visual arts (2016) in the city of Monterrey, Mexico, for instance, was criticized for its contradictions. While it was specifically asking how “to decolonize our imaginaries from the promise of happiness sustained on consumption, accumulation of material goods and economic policies of unlimited growth”, it was at the same time supported by FEMSA, one of the biggest Mexican corporations, presented as “an example of continuous growth and expansions.”11 Contradictions are not rare. Often cultural institutions are only thematically addressing the problematics of growth and not examining their own progress-oriented principles, goals, sponsors, code of ethics and modes of operation. Tate Modern, as it is widely known, faced numerous acts of protest against the sponsorship by BP which finally ended in 2016. Since a few years, a rich program of events related to the environmental issues is presented while a detailed and transparent program regarding climate action and sustainability is applied.12 This is the direction that most big art institutions are now embracing using sustainability tools and advisory networks in an attempt to reduce their carbon footprint and to influence individuals, collectives and institutions in societies to take action. The recent Helsinki Biennial (2022) was an event that has greatly succeeded this thematically and practically carefully assessing the environmental cost of all activities, reducing decisively traveling, freight, waste.13

When it comes to topics such as degrowth, a holistic approach and a form of planning based on an “adaptive capacity” is needed. This according to Paul Gray et al. would be the result of “a unique combination of values and principles, institutional culture and function, commitment to public engagement, financial and human assets, acquisition and use of information, know-how and a mandate for decision-making.”14 An event also worth mentioning within this context is RAUPENIMMERSATTISM (2020)15 realized at Savvy Contemporary in Berlin. Just like the other shows mentioned RAUPENIMMERSATTISM discussed “the myth of endless consumption” but with an important twist. The team of Savvy decided to turn its attention to those found at the other side, the ones living in poverty and the margins, having to survive with the leftovers of the capitalist system. The show exemplified the problematics of growth and affluence by discussing openly and directly the paradoxes found in one of world’s most powerful economies, Germany.

No matter how much art institutions might try to adapt their programs, another factor needs to be taken in mind with regard to degrowth. Art institutions themselves keep increasing in number and the same happens with their activities.16 There is at the moment a problem of overproduction. A certain event or else gig- economy prevails in the arts and affects the way independent curators and artists work. A pressure for new ideas, new projects, new constellations, leaves little room for change in the rhythm of production. Questions of storage and preservation with reference to works and exhibition materials remain open. Realizing this, Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez addressed a call for institutions and curators to slow down and pay attention to quality of research, to collective work, to sustainability and resilience, and to pay attention to levels of engagement with the public and the team. Such a shift would redefine the role of the arts in taking a critical stance and having an influential role in society, but hardly would it involve the art market. In a recent article of his, Julian Stallabrass reminds us that it is always the “gravitational force of money that bends art”.17

Stallabrass underlines the trap of generalization in the case of the arts. There is not one art world but “many divergent intersecting circles” with different economies, audiences, shows, and importantly, artists. Similarly, in the case of degrowth there might be biennials, festivals and exhibitions like the ones mentioned in this article that emphasize exit, conviviality and interdependence, but the art fairs and the art market itself have little interest in the topic. The art world remains fragmented and paradigms of artistic practice with reference to degrowth are to be found mostly outside the art market. These are works based on research and experimentation examining the limits of growth and discussing its costs to populations, ecosystems and the planet itself. Studying examples of such projects, one realizes how artistic production itself can assist in a process of downscaling and how artists address the topic following different methodologies.

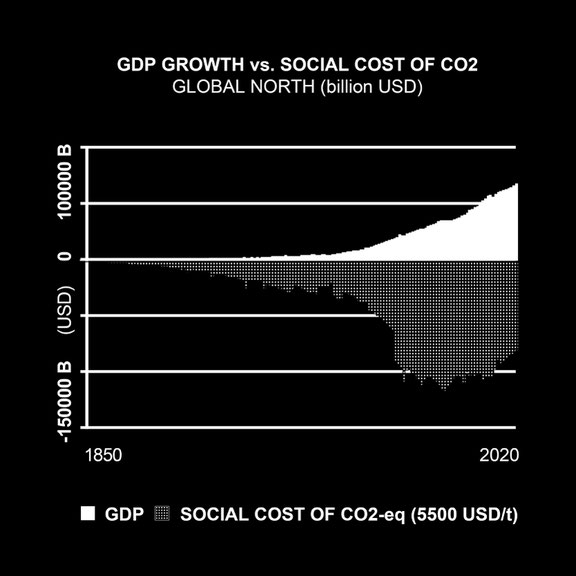

Post Growth (2020) is a project developed by Disnovation.org working at the intersection of contemporary art, research and hacking in collaboration with artist, curator and writer Baruch Gottlieb.18 The project takes its title from Tim Jackson’s book Post Growth – Life after Capitalism and uses the term “as a container for desirable futures beyond the imperative of growth”19 “which is driven by international finance”.20 For them, at the core of the discussion on growth lies in their opinion the issue of energy. The project unfolds around a series of different units consisting of interviews, a toolkit, prototypes, a game and a living installation, all shedding light to different aspects of energy production and consumption. Some of the formats are participatory because they want people to engage with the topic directly, by sharing experiences and stories, seen as they say as “tools for transmission and collective discussion”.21 Referring to the energy produced by fossil fuels (which means by remains of ancestral organisms), to the role of ecosystems in energy processes, as well as to the energy that human bodies produce and consume, the group stresses that such information and knowledge need to become accessible. Similarly, with their following project ShadowGrowth (2021)22, a digital tool assessing and depicting CO2 emissions as opposed to GPD numbers, they revealed hard truths about growth.

A number of projects created by Superflux, a group working on art and speculative design, points to the importance of trying to imagine what the world would be like after the myth of growth has collapsed. Their scenarios which emerge through large scale installations, objects and videos are not necessarily dark and pessimistic. They rather tell stories of “active hope”, driven by “ideas, myths, stories, objects that can help people navigate precarity”.23 Superflux imagine the day when a new world will be born in the ruins of the world that chased progress. Refuge for Resurgence (2021)24 introduces a symbolic scenery where different species are invited to sit together on one dining table with unusual wooden cutlery and furniture planned to accommodate all. Their film Intersection (2021)25 invites viewers to imagine what will happen after states, media and the market have damaged societies and the planet. This will be possibly the era of the “Craftocene” as they call it, when tools will be made from the waste of the Anthropocene, and this crafting will help to build not just tools but also worlds, as Anab Jain explains.26 Questioning human centered design, Superflux address a call for a more-than-human politics through a manifesto that underlines the need to change values and scopes passing from “fixing to caring”, from “innovation to resurgence”, from “independence to interdependence”.27

For Valentina Karga, artist, designer and professor in design, it is the study and understanding of closed systems that can assist creators to change their perspective. Approaching the earth itself as a closed system and as an infrastructure, she underlines how dependent we all are on it. “Nature, planet Earth, with its materiality” is what she calls “infrastructures’ infrastructure, because all the materials we use to make our infrastructures are eventually coming in some form from there (since Earth is materially closed).”28 Since her early work, Karga experimented with strategies of self-sufficiency concerning energy and food. Karga proposes an adoption of DIY and collective techniques based on the sharing of experience and knowledge as this is the only way “to learn to practice together under a (post human) commons worldview, something that has been largely neglected in the past”. The artist emphasizes the importance of using organic materials, such as natural dyes, natural textiles, reused wood, hay and clay, that can be composted, if necessary, or inorganic minerals that are not bound together under chemical processes such as rammed earth instead of concrete, and for artistic production. One of her most recent works is a self-compostable sculpture. Made of cotton fabric, cardboard, soil, hay and corn leaves, and waste, The table that eats itself (2022)29 was designed for people to sit around and join a dining performance feeding themselves and the table, helping it to compost itself while engaging in discussions about myths of progress, capitalism, needs, food and waste.

Practices of degrowth are based on collective but also individual action involving self-reflection regarding one’s own activity and impact on the planet. Matthias Fritsch is an artist and filmmaker researching circles of matter and biological processes. Through his work, he is studying the habits and rhythm of the planet’s human and nonhuman inhabitants. He focuses on the impact of anthropogenic activity on soil and the living environment while introducing prototypes for more sustainable living. Among those are a set of 13 personal commandments, indoor composting furniture, fermentation techniques, and gardening strategies for a changing climate.30 For a recent project of his, the Mycelium Garden (2022)31 Fritsch explored the role of fungi in breaking down organic matter, feeding on energy and forming the basis for plants’ life. Created and presented as a living sculpture made of fungi, organic material and a wooden structure, the work had its own cycle with the artist as its daily gardener. The installation differed from day to day with moments of blooming and moments of harvest. The harvest of edible mushrooms was offered to the visitors and the staff of the institution. The numerous mycelium bags were distributed to people interested in cultivating mushrooms after the show finished. The structure was disassembled back to its original components for reuse and literally left no trace of waste behind.

Interestingly, artistic works like the ones mentioned above refer to the day after, to the period after a possible sociopolitical and environmental collapse, and propose speculative or pragmatic strategies, prototypes and tools. They are direct and consequent, questioning accumulation and growth. Works made of organic material, based on living organisms, that change over time or capture the traces of human activity on the planet are works that make people aware of time and scale. The artists invite audiences to observe and acknowledge changes, and to realize that life on the planet is based on individual and collective action, on interdependence and conviviality. As Liegey and Nelson write, degrowth is anyway “an invitation to go on the inevitably long journey of the decolonization of our growth imaginaries, moving from cultural awareness to a systemic and material transformation changing our everyday practice”32. In the field of the arts, both institutions and the people working in the field need to reassess priorities, to set goals and to work collaboratively, planning works and events that address the needs of the audiences, involve them, and respect the environment. Possibly this is the only way to escape contradictions and move towards a reality where open discussions about growth can happen, sustainability goals are reached, and also the arts themselves with their places and people are safe and secure.

1 André Gorz, Ecology as Politics, trans. by Patsy Vigderman and Jonathan Cloud (Boston: South End Press, 1980), 13.

2 Ibid., 8.

3 Matthias Schmeltzer, Andrea Vetter, Aaron Vansintjan, The Future is Degrowth: A Guide to a World beyond Capitalism. (London/New York: Verso, 2022), 159.

4 Ivan Illich, Tools for Conviviality. (London: Marion Boyars, 2001).

5 Vincent Liegey & Anitra Nelson, Exploring Degrowth: A Critical Guide. (London: Pluto Press, 2020), 12.

6 Ibid., 83.

7 Schmeltzer, Vetter, Vansintjan, 180.

8 https://www.fkv.de/en/exhibition/uber-die-metapher-des-wachstums/

9 https://www.lafermedubuisson.com/fr/plus-de-croissance-un-capitalisme-ideal

10 Serena De Dominicis, “Art against growth. Looking at the possibilities offered by the gift paradigm”, https://www.academia.edu/34869801/Art_against_growth_Looking_at_the_possibilities_offered_by_the_gift_paradigm

11 Sofia Avila, “Degrowth in the Mexican Art Biennial: Opportunities and Paradoxes”, https://degrowth.info/de/blog/degrowth-in-the-mexican-art-biennial-opportunities-and-paradoxes

12 https://www.tate.org.uk/about-us/tate-and-climate-change

13 https://helsinkibiennaali.fi/

14 P. A. Gray et al., “Strategies for Coping with the Wicked Problem of Climate Change,” The Future of Heritage as Climates Change: Loss, Adaptation and Creativity, eds. David Harvey and Jim Perry (New York: Routledge, 2015); also discussed in the article by Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez mentioned later in this article.

15 RAUPENIMMERSATTISM (in German: Die kleine Raupe Nimmersatt) means “The Very Hungry Caterpillar”; it is a children's picture book designed, illustrated, and written by Eric Carle, first published by the World Publishing Company in 1969, as explained at the webpage of the exhibition, https://savvy-contemporary.com/en/projects/2020/raupenimmersattism/

16 Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, “For Slow Institutions”, e-flux Journal, Issue 85 (2017), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/85/155520/for-slow-institutions/

17 Julian Stallabrass, “Contemporary art is popular – but it’s still about money and power”, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/stallabrass-contemporary-art-market-audience/

18 https://disnovation.org/postgrowth

19 Personal communication with Nicolas Maigret, 2022.

20 Personal communication with Baruch Gottlieb, 2022.

21 Maxence Grugier, “Post Growth: a Toolkit for Radical Transitions (½)”, https://www.makery.info/en/2021/03/01/post-growth-imagine-la-boite-a-outils-de-lapres-croissance-1-2/

22 http://shadowgrowth.earth/

23 Daphne Dragona, “Interview with Superflux”, Neural Magazine, Issue 71.

24 https://superflux.in/index.php/work/refuge-for-resurgence

25 http://the-intersection.io/

26 https://superflux.in/index.php/work/the-intersection/#

27 http://superflux.in/index.php/a-more-than-human-manifesto/#

28 Daphne Dragona & Valentina Karga, “What Supports Us: A conversation about Infrastructures”, Current – Art and Urban Space, eds. L. Bernhardt, J.-L. Zajaczkowska & N. Unger (Stuttgart 2022), 9.

29 As presented at EMAF 2022 with the title “The Thing is”, https://www.emaf.de/work/?id=36000&lang=en

30 https://www.technoviking.tv/subrealic.net/

31 As presented at the exhibition Weather Engines at Onassis Stegi in 2022, https://www.onassis.org/art/works/mycelium-garden

32 Liegey and Nelson, 12.