When British writer Arthur C. Clarke visited Bell Labs in the mid-fifties to learn about the spectacular postwar developments in communication technology in the United States, he encountered a strange automaton called “The Ultimate Machine” in Claude Shannon’s office. Shannon’s seminal papers on cryptography and on the mathematical foundation of communication from World War II were undergoing declassification at that time and his name was becoming better known to the world for having invented information theory. In 1952, Shannon constructed this curious toy and was proud to show it to his visitors. His demonstration produced an immediate effect on Clarke and, indeed, on almost everyone who had the opportunity to see it. Here is how Clarke reports his first encounter with the machine thus:

“Nothing could look simpler. It is merely a small wooden casket the size and shape of a cigar-box, with a single switch on one face. When you throw the switch, there is an angry, purposeful buzzing. The lid slowly rises, and from beneath it emerges a hand. The hand reaches down, turns the switch off, and retreats into the box. With the finality of a closing coffin, the lid snaps shut, the buzzing ceases, and peace reigns once more. The psychological effect, if you do not know what to expect, is devastating. There is something unspeakably sinister about a machine that does nothing—absolutely nothing— except switch itself off.”1

It is said that the conception of “The Ultimate Machine” was initially proposed by Shannon’s fellow scientist named Marvin Minsky who, as I will discuss below, would soon become the founding father of a discipline called Artificial Intelligence (AI). Shannon was immediately struck by Minsky’s idea and went ahead to design the machine and built a few models. The psychic impact of his automaton was so uncanny that according to Clarke “distinguished scientists and engineers have taken days to get over it. Some have retired to professions which still had a future, such as basket-weaving, bee-keeping, truffle-hunting or water-divining. They did not stop to ask ‘For Whom the Bell Labs Toll’.”2 Clarke himself was clearly shaken by the “unspeakably sinister” aspect of the automaton which almost embodies the death drive itself. He used the word “devastating” as if reacting to some dark intentions that emanated from the machine. How could an artificial hand that did “nothing” other than appear and disappear produce such extraordinary effect on the human psyche?

Half a century went by, and Shannon’s contrivance can no longer surprise us. We are surrounded these days by people who talk about cyborgs, androids, and posthumans with great excitement and many are infatuated with robots. We either love them or hate them and we let them dominate our dreams and our social lives. It is as if we are caught in a narcissistic loop of human-machine simulacra. Recognizing this, Rodney Brook proclaimed fifteen years ago “the distinction between us and robots is going to disappear.”3 but it seems to me that something more profound and uncanny is taking place. We ought to ask some new questions about the blurred distinction between humans and machines: Are human beings evolving into some type of Freudian robots at the same pace as AI engineers design their robots to resemble humans? In short, is the Uncanny Valley becoming a two-way street?

To investigate the curious human-machine simulacra, one may pursue a sociological diagnosis of the social media or adopt the model of cultural criticism to analyze the younger generation’s behavior in the age of digital technology. Many journalists and scholars have done precisely that. But we also need a well-grounded theoretical grasp of the problem when confronted by human-machine simulacra. Which problem? Is there anything wrong with our obsession with the intelligent machine? Why should we worry about such obsession and study it?

If my hypothesis is correct, that is, human beings are evolving to resemble the intelligent machines we invent even as we build robots to behave more like humans, the result of the ceaseless feedback loop is a new generation of cyborgs with peculiar human-machine interfaces. I have a name for this new species, that is, a species of “Freudian robots”. After having written a book about it, I am now prepared to say that the Freudian robot figures the ultimate uncanny in our collective unconscious. Let me elaborate on what I mean by that by focusing on three interrelated points in my lecture: 1) Austrian psychoanalyst Freud’s fascination with automata when he wrote his essay “The Uncanny” in 1919; 2) Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori’s hypothesis of the Uncanny Valley; 3) American AI scientist Marvin Minsky’s “Emotion Machine.”

Back to Freud: Automata in “The Uncanny”

We have observed how the mechanical hand in Shannon’s “Ultimate Machine” achieved an uncanny effect by simulating the gesture of the human hand. The simulation of the independent movement of severed limbs is closely related to Freud’s fascination with automata when he wrote his essay on “The Uncanny” in 1919. In his analysis of the story of “The Sandman” by E.T.A. Hoffmann, Freud pays close attention to dismembered limbs, a severed head, a hand cut off at the wrist, or feet that dance by themselves, etc.

It is worth noting that Freud was responding to an earlier study of the uncanny by Ernst Jentsch (1906) who was the first to link the uncanny with automata through his reading of Hoffmann’s story “The Sandman.” In his paper entitled “Zur Psychologie des Unheimlichen” (On the Psychology of the Uncanny), Jentsch speculates that of all the psychical uncertainties which may cause the uncanny feeling to arise, one in particular is likely to develop into a regular, powerful, and general effect. This concerns the doubt as to whether an apparently living being is animate or not and, conversely, the uncertainty about whether a lifeless object may not in fact be alive, as, for example, when a tree trunk is perceived to suddenly move and shows itself to be a giant snake or a wild man experiences his first sight of a locomotive or a steamboat. Among the other lifeless objects which fall into the same category of the uncanny, he mentions wax figures, panopticons, and panoramas and, above all, draws our attention to automatic toys, life-size automata which can perform complicated tasks like blowing trumpets and dancing, and dolls that can close and open their eyes by themselves. In that sense, Shannon’s “Ultimate Machine” would fit perfectly Jentsch’s image of the uncanny as do many of the cybernetic toys of our own time.

Jentsch further speculates that the uncanny is a semi-conscious projection of the self onto an object even as the object returns to terrify the self in the image of that self-projection. For this reason, human beings are not always capable of exorcising the spirits which have been fabricated out of our own heads and this inability produces the “feeling of being threatened by something unknown and incomprehensible that is just as enigmatic to the individual as his own psyche usually is.”4 In storytelling, Jentsch suggests, one of the most reliable artistic devices for producing uncanny effects is to leave the reader in a state of uncertainty about whether he is dealing with a human being or an automaton. “In his works of fantasy,” he adds, “E.T.A. Hoffmann has repeatedly made use of this psychological artifice with success”; namely, is the doll Olympia in “The Sandman” animate or inanimate?

It is interesting that Freud rejects Jentsch’s argument of intellectual uncertainty and looks elsewhere for the sources of the Unheimlich. He begins by focusing on what Hoffmann’s language can tell us about repression. Freud writes: “We can understand why linguistic usage has extended das Heimliche [‘homely’] into its opposite, das Unheimliche; for this uncanny is in reality nothing new or alien, but something which is familiar and old-established in the mind and which has become alienated from it only through the process of repression. This reference to the factor of repression enables us, furthermore, to understand Schelling’s definition of the uncanny as something which ought to have remained hidden but has come to light.” Tracing the sources of repression, Freud detects beneath the character Nathanael’s ocular anxiety a deeper and symptomatic fear of castration. He writes: “This automatic doll can be nothing else than a materialization of Nathanael’s feminine attitude towards his father in his infancy.” Is the uncanny fundamentally linked to the castration complex? Freud said yes, but others have disagreed.

Hélène Cixous, for instance, suggests a different reading of the uncanny by demonstrating a close connection between Hoffmann’s fantastic tale and the puppet theatre that once populated the stages of German romanticism. She points out: “What unfolds without fail before the reader’s eyes is a kind of puppet theater in which real dolls or fake dolls, real and simulated life, are manipulated by a sovereign but capricious stage-setter.”5 We may thus infer that the puppeteer in “The Sandman” is the writer Hoffmann who sets in motion those literary puppets designed to tease our emotional and cognitive reaction to what he terms the uncanny. The medium of Hoffmann’s automata is the puppet theatre in which the puppeteer and his audience or readers engage in a psychic game of make belief about what is alive and what is dead. In this theatre, which serves as the medium for the puppet performance, it does not take long before the clumsy doll Olympia created by the scientists/alchemists Spalanzani and Coppola is detected and exposed for what she is, but what about Nathanael? Obviously, it is more difficult for us to make a quick decision about his animate or inanimate state.

In my view, Nathanael is probably the cleverest automaton to be invented by fiction writer Hoffmann to compete with the inferior doll Olympia designed by the scientists. Unlike Jentsch who read the story at face value, Freud looked in the right place—i.e., in Nathanael rather than in Olympia—but missed the automaton in Nathanael. This is a little strange because we know that Freudian took a keen interest in the mechanisms of the unconscious. For example, he discussed the camera obscura and the mystic writing pad and their relationship to the unconscious. In The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud states: “we should picture the instrument which carries out our mental functions as resembling a compound microscope or a photographic apparatus, or something of the kind. On that basis, psychical locality will correspond to a point inside the apparatus at which one of the preliminary stages of an image comes into being.” Will today’s automata and sophisticated works of artificial intelligence invoke the same feelings of the uncanny as did Hoffmann’s story for Freud? Indeed, what do we know about the psychic life of intelligent machines? These questions will take us to the work of Japanese robot engineer Masahiro Mori whose hypothesis of the Uncanny Valley for the AI industry has been greatly influential over the past several decades.

The Uncanny Valley

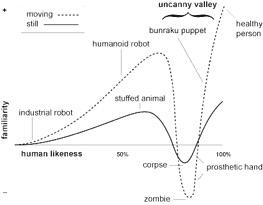

One of the latest developments in this area has emerged from the work of engineers, robot scientists, and psychiatrists in what has been termed the Uncanny Valley hypothesis. This hypothesis was first put forward by Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori in 1970 who speculated that as robots become progressively humanlike, our sense of empathy and familiarity increases until we come to the “Uncanny Valley” and at this point the robots will start to elicit negative feelings in us. After surveying the various kinds of prosthetic hands, Mori suggests that as the new technology further animates the prosthetic hand by enabling prosthetic fingers to move automatically, this will cause the animated hand to slide toward the bottom of the uncanny valley. The above diagram illustrates how Mori has worked out this hypothesis after Freud.

Mori places the healthy person at the top of the second peak and the prosthetic hand near the bottom of the Uncanny Valley which may remind us of the effect of Shannon’s “Ultimate Machine” upon the writer Arthur Clarke. Mori notes that “our impression of death can be explained by the movement from the second peak to the uncanny valley as shown by the dashed line in the figure. We might be happy this line is into the still valley of a corpse and that of not the living dead! I think this explains the mystery of the uncanny valley: Why do we humans have such a feeling of strangeness? Is this necessary? I have not yet considered it deeply, but it may be important to our self-preservation.6 If this comes close to how Freud had interpreted the uncanny and the death drive, Mori quickly adds, however, that his goal is to “design robots or prosthetic hands that will not fall into the uncanny valley” and this seemingly out of respect for our death drive as Freud would have put it.

The provocative questions posed by the Japanese roboticist have since led to what is widely known as the Uncanny Valley research and, over the past decades, that research has taken off in all sorts of directions ranging from robot engineering to computer games or subcultures, but the primary concerns remain more or less constant as the scientists try to explore the emotional and cognitive impact of humanoid robots, automata, and social robots upon human beings. In recent years, cognitive scientists Frank Hegel, Sören Krach, and their team have applied functional neuroimaging methods to the phenomenology of human-robot interaction. Focusing on the varying degrees of anthropomorphic embodiment of the robot, they begin with the assumption that the majority of intersubjective non-verbal cues are communicated by the human face and, therefore, the design of a robot’s head becomes central to the experiment. As the physiognomy of a robot affects the perceived image of its humanness, we are told that human participants prefer to interact with “positive” robots and avoid negative looking robots or negatively behaving robots, whatever their negativity is supposed to mean at social and psychic levels. What is interesting about this group’s work is the claim that their hypothesis has drawn on Freud’s notion of the uncanny which “derives its terror not from something externally alien or unknown but—on the contrary—from something strangely familiar which defeats our efforts to separate ourselves from it.”7 The partners to this game consist of a computer, a functional robot, an anthropomorphic robot, and a human partner. The more a robot looks and behaves like a real human being, the more expectations the human partner seems to have of its abilities and the result is often a negative reaction from the human observer, and so on. Freud himself would have taken a keen interest in such experiments. However, the question is whether the result of these studies can really tell us anything new about the uncanny. Or does it simply reflect the scientists’ view of how the human brain works with respect to the intentions or desires of others in an already socialized game setting? If so, where do we turn for new insights in the study of the uncanny?

Marvin Minsky’s Emotion Machine

The popular robot HAL in the 1968 Kubrick film 2001: A Space Odyssey was inspired by the AI developments in the U.S. and by some of the actual robots that screenplay writer Arthur C. Clarke encountered in MIT’s Artificial Intelligence Laboratory. This laboratory was founded and directed by late Marvin Minsky who is widely regarded as the founder of Artificial Intelligence and robotic science. One question that is seldom raised by those who study AI is the following: Where does Freud stand in Minsky’s work on robotics and in the AI research programs initiated by him? Earlier, I speculated on a possible psychoanalytic reading of “The Ultimate Machine” as a figure for the death drive. As a matter of fact, Minsky had long engaged with Freud and psychoanalysis in unique and fascinating ways. We find his acknowledgement of Freud in books like The Society of Mind in 1986 and The Emotion Machine in 2006. Minsky’s work suggests that Freudian psychoanalysis has shadowed the cybernetic experiments of AI engineers and theorists throughout the second half of the twentieth century down to the present.

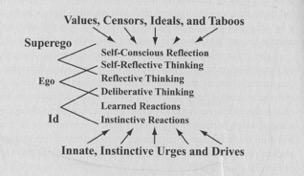

Minsky’s pioneering work on randomly wired neural network machine was inspired initially by Warren McCulloch’s and Walter Pitt’s work on neural nets. Later, he professes conflicting allegiance to McCulloch and Freud and practically characterizes his own project as “neo-Freudian.” With the AI robotics program in mind, Minsky draws on Freud’s ideas about the unconscious and tries to reformulate them with the help of Jean Piaget’s work on cognition and learning processes. This is a difficult enterprise, because a humanoid robot is a much more ambitious and complex simulation project than Colby and his team could possibly envision with their neurotic machine and PARRY. The construction of such robots entails formidable technical obstacles and, more important, it raises fundamental philosophical issues about cognition, memory, reflexivity, consciousness and so on. For example, what makes human beings unique or not so unique? Or what is it that makes robots endearing or uncanny to humans? In developing his robotic model of the mind, Minksy frames these problems in explicitly Freudian terms as is demonstrated by the above diagram from his book The Emotion Machine.

Minsky calls his diagram “The Freudian Sandwich” in which the Id, Ego, and Superego are duly replicated in that order. The main difference is that his particular model—rather than some alternatives—also serves as a model for humanoid robots. The future robot must be fully equipped with “mental” correctors, suppressors, censors and so on to allow it to function at a highly intelligent level. This neo-Freudian approach leads to his dismissal of rationality as “a kind of fantasy.” Minsky argues that “our thinking is never entirely based on purely logical reasoning” and predicts that “most of our future attempts to build large, growing Artificial Intelligences will be subject to all sorts of mental disorders.”8 What is more interesting, fictional robot HAL-2023 pops up in the midst of his discussion to confirm that “my designers equipped me with special ‘backup’ memory banks in which I can store snapshots of my entire state. So whenever anything goes wrong, I can see exactly what my programs have done—so that I can then debug myself.” If this sounds like science fiction, Minsky proposes that “we must try to design —as opposed to define—machines that can do what human minds do” because until one can simulate the cognitive machinery of the mind in all its respects, one cannot fully understand how the human mind works.

Minsky’s formulation of the cognitive unconscious consists of Frames, Terminals, Network Systems as well as Bugs, Suppressors, and other mechanisms of a network of interacting subsystems. Their functions seem not very different from the general workings of the unconscious as originally formulated by Freud except that Minsky rejects any association of nonsense with some basic “grammar of humor” or “deep structure.” The lack of unity in the unconscious derives from the interplay of sense and nonsense in a complex web of relations among laughter, faulty reasoning, taboos and prohibitions, and unconscious suppressor mechanisms in the unconscious. For that reason, the pursuit of semantics can never get us very far when the “clarity of words is itself a related illusion” as far as the cognitive unconscious is concerned.

Minsky does not shun complexity nor does he approach the cognitive unconscious via semantics and established concepts. The latter—verbal sense and nonsense—may be explained by the complex pathways of the interconnected network systems in the unconscious. How large and how complex are the interconnected network systems in the human cognitive unconscious? No one has an answer yet. Minsky speculates that “it would take more than a million linked-up bits of knowledge, but less than a billion of them, to match the mind of any sage.” Would this put the computer simulation of the human mind out of the question? Minsky believes that such a task is indeed difficult but not out of reach.

To design machines that can do what the human mind does is to build the Freudian robot of the future. Why humanoid robots? Minsky would reply that this has something to do with our dream of immortality. If the question is “Is it possible, with artificial intelligence, to conquer death?” his answer is an unequivocal yes. He further predicts that human beings will achieve near-immortality by using robotics and prosthetic devices. We will be able to replace all damaged body parts including our brain cells and live a healthy and comfortable life for close to ten thousand years. And we can even transfer our personality into the computer and become computers—i.e. Freudian robots—and “we will be able to install in a human form an intelligence uncannily close to our own.” The word “uncannily” slips out from somewhere to state the true ambition of AI research. As a self-styled neo-Freudian, Minsky has somehow neglected to consider the mechanisms of repression with respect to death.

Will death ever be conquered? Is the desire to master the unconscious a manifestation of the death drive that Freud has discerned in the human civilization? The familiar psychic defense mechanisms that Freud identified long ago now bring us face to face with the return of the repressed in the work of Minsky and other AI scientists. Their robots are Freudian robots in the sense that they embody the ultimate uncanny in our collective unconscious.

1 Arthur C. Clarke, Voice Across the Sea (New York: Harper & Row, 1959), p. 159.

2 Ibid.

3 Rodney A. Brooks, Flesh and Machines: How Robots Will Change Us (New York: Vintage Books, 2003), p. 236.

4 Ernst Jentsch, “On the Psychology of the Uncanny,” p. 14; translated from “Zur Psychologie des Unheimlichen,” in: Psychiatrisch-Neurologische Wochenschrift, 8.22 (25 Aug. 1906), pp. 195–98 and 8.23 (1 Sept. 1906), pp. 203–5.

5 Hélène Cixous, “Fiction and Its Phantoms: A Reading of Freud’s ‘Das Unheimliche’

(the ‘Uncanny’),” in: New Literary History, 7, no. 3 (1976), p. 525.

6 Masahiro Mori, “Bukimi no tani” (The Uncanny Valley), in: Energy 7, no. 4 (1970), p. 35, translated by Karl F. MacDorman and Takashi Minato in appendix B in MacDorman, “Androids as an Experimental Apparatus: Why Is There an Uncanny Valley and Can We Exploit It?”, p. 9-10; Cognitive Science Society Workshop on “Toward Social Mechanisms of Android Science”, 2005; https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/f563/907a01673e8dcf22a0455bbe1a9f9106a123.pdf?_ga=2.207138452.600410490.1580397189-751674446.1574090387

7 F. Hegel, S. Krach, T. Kircher, B. Wrede, and G. Sagerer, “Theory of Mind (ToM) on Robots: A Functional Neuroimaging Study,” in: Proceedings of the 3rd ACM/IEEE international Conference on Human Robot Interaction, Amsterdam, Netherlands, March 12–15 (2008), p. 336; http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1349866.

8 Marvin Minsky, The Emotion Machine: Commonsense Thinking, Artificial Intelligence, and the Future of the Human Mind (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2006), p. 341.